030. Science Fiction Reliquary (II)

Darko Suvin, credited by many academics as the originator of science fiction criticism, defines the genre as one of “cognitive estrangement” where worlds and technologies are created in defiance of...

Hello friends,

Literary scholar Darko Suvin, credited by many academics as the originator of science fiction criticism, defines the genre as one of “cognitive estrangement” where worlds and technologies are created in defiance of our present moment’s empirical logic.

I feel the need to point this out because the “strange” part of science fiction tends to get buried under CGI special effects, awe-inspiring technological predictions, and heroic narratives. I find that the most successful works of SF are the ones that not only inspire you, but unsettle you in some way by challenging and pushing the boundaries of what our societies deem “normal” or, even, “human.” That SF was birthed from supernatural folklore and myth is no surprise. Even in our wildest imaginations of powerful machines, of distant planets, of other worlds, science fiction always manages to return back to the human body, transformed, a reminder that acknowledging our past and present is the key to understanding our futures.

TOUCH

I absolutely adore this “Queering Sci Fi” tote bag from Martian Press! Run by artist Stephanie Lane Gage out of Los Angeles, this small press creates gorgeous risograph prints and zines centered around an otherworldly approach to design. I love how this particular tote emulates a retrofuturistic flare, and it’s a great reminder that, as we think of speculative fiction, we should imagine futures that go beyond our limited ideas of gender and sexuality. Already bursting at the seams with books, I can’t wait to take this with me everywhere I go.

Jeff VanderMeer’s Borne takes place in a city ravaged by renegade biotech, where leftover humans and roving gangs of mutants clash in violent struggles for survival. Within this post-apocalyptic landscape, one such scavenger comes across a mysterious creature. Not quite animal, not quite plant, Rachel tries to make sense of Borne and his unprecedented growth and hunger. Encounters with non-humans are nothing new in SF. Yet, I love how VanderMeer presents Borne’s ‘monstrosity’ as a relentless hunger to learn, absorbing the world and adapting to it. This book is more than an allegory for genetic modification and corporate greed, entangling itself with an existential wonder about the ways we define humanity and build resiliency in environments of hostility.

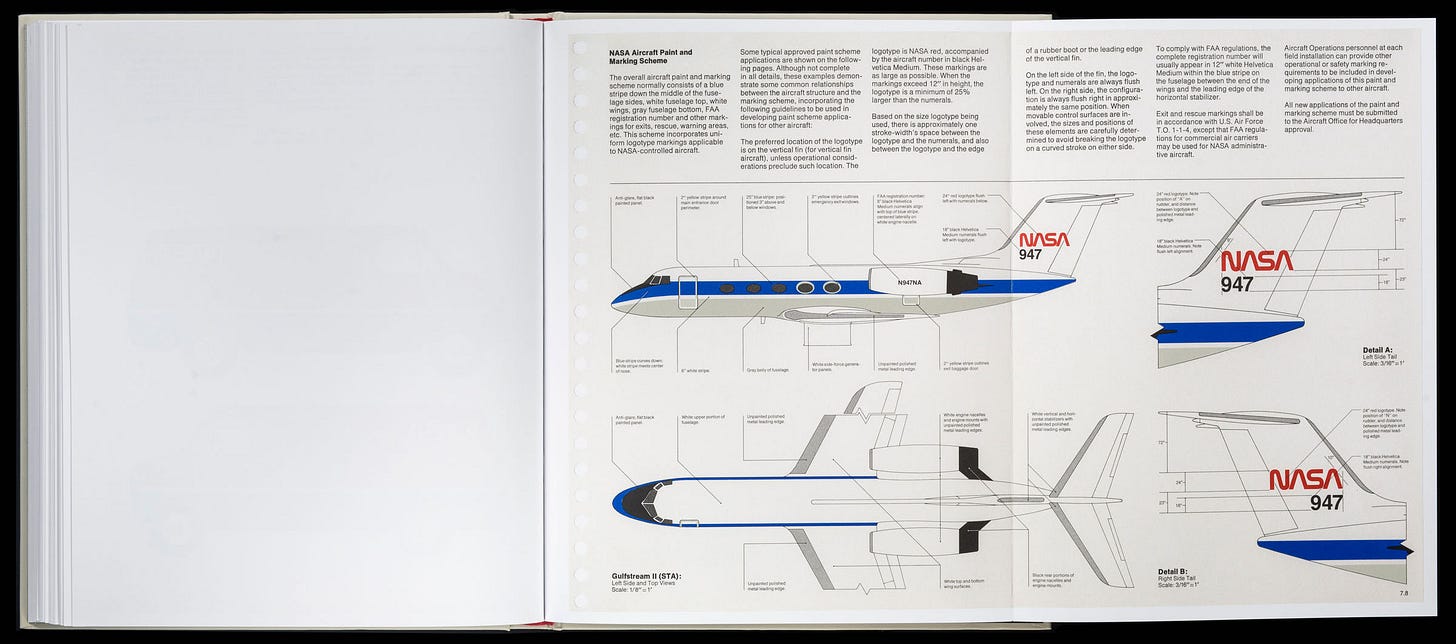

I know NASA is a real organization, but I am so fascinated by this Graphic Standards Manual from 1975. Created for the space agency’s use, it’s amazing to see how designers Richard Danne and Bruce Blackburn developed such a comprehensive visual language of sleek, minimalist futurism coupled with governmental utility. From sign typography to paint patterns on NASA vehicles, no detail is left unimagined. Although the guide was phased out in 1992, I’m sure you’ll find aesthetic parallels to design elements throughout SF film and television.

While we’re on the subject of space travel, let’s talk about one of my favorite mangas, Planetes. Set in 2075, Planetes follows a space debris cleanup crew as they confront their pasts and try to advance their careers. What I love about this series is that it doesn’t romanticize the world of interplanetary travel. Life on Earth is plagued with concerns over climate change, terrorists target stations, companies seek to explore the deepest corners of the solar system for resource extraction, and we are confronted with outer space’s isolation. Full of technological marvels, it’s a great story to escape into.

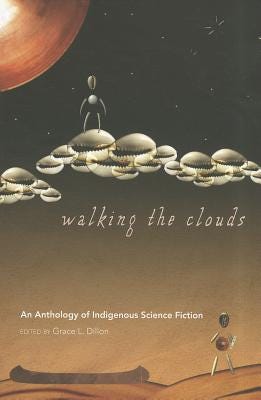

If you want to learn more about Indigenous SF, I can’t recommend Grace L. Dillon’s anthology, Walking the Clouds, enough. Broken down into themes like “Contact,” “Indigenous Science and Sustainability,” “Native Slipstream,” and “Native Apocalypse,” each story uses science fictional elements to share cultural history, time travel, and reckon with the impacts of colonization through speculative craft. With authors from all parts of the world, including First Nations, Native American, Taino, Aboriginal folks, you are sure to find a new favorite SF writer. My personal favorites: an excerpt from Nalo Hopkinson’s Midnight Robber of exile and nonhuman encounters, a piece Celu Amberstone’s novella Refugees about alien invaders, and an excerpt from Andrea Hairston’s first novel Mindscape about an apocalyptic organism.

Fred Scharmen’s Space Settlements is equal parts criticism and historiography, looking at an ambitious NASA-led meeting of urban planners, architects, and artists to create space habitats. Meant to house millions of people, like floating nations, these plans were meant to sustain human life while orbiting around planets. You may even recognize some of these cylindrical forms or modular geometry and landscaping. Scharmen looks at how these ambitious speculative projects both failed and and succeeded in shaping spatial design and capturing our cultural imagination.

LOOK

Cristina De Meddel’s Afronauts is a photo-documentary series that recreates the attempt of a Zambian science teacher to send the first African crew into outer space shortly after the country’s independence 1964. Outfitted in spacesuits made from ornate African textiles, De Meddel photographs these explorers traversing lunar desert landscapes, concrete mixing drums double as crashed ships. These gorgeous images are a testament to a young nation’s interstellar ambitions.

Katrin Spranger’s copper and glass sculptures look like pieces of plumbing suddenly contaminated and mutated. Spranger makes these bacteria-like surfaces by painting her materials with a conductive paint before running an electric current through the sculpture until the copper deposited layers of this gooey form. This piece, from her series Aquatopia, contemplates freshwater consumption and waste, and the dystopian possibilities of a world marked by severe water shortages. In an interview, Spranger notes that she chose these materials deliberately, “Decorative, plant-like growth formations on each vessel symbolize that life is completely dependent on water.”

Anna Dumitriu uses bacteria as her medium of choice for her futuristic artworks. Projects like ArchaeaBot, Plague Dress, and Make Do And Mend (pictured above) use synthetic biology and samples of viruses like penicillin to consider bacteria resistance in medicine, new definitions of life based on ancient micro-organisms, and weave textiles and fiber art into historical narratives of science, making, and robotics.

Larissa Sansour’s film and photography practice merges imagined science fiction with cultural history and archeology, with a specific focus on Middle Eastern aesthetics and politics. Works like In The Future They Ate From The Finest Porcelain and Until It Was Black feature invented civilizations while exploring national identity and myth. My personal favorite is In Vitro from 2019 where, under the town of Bethlehem, an orchard grows where an environmentally disastrous nuclear reactor once stood.

LISTEN

Throughline's episode about Octavia Butler is a phenomenal tribute to one of modern science fiction's greatest legends. Featuring interviews with SF authors and creatives who learned from and built on Butler's Afrofuturist, feminist storytelling, one can't help but be left awestruck by her novels' continued impact. From the immortal Africans of Wild Seed to Parable of the Sower’s prophetic social collapse, Butler reckoned with America’s complex racist history while imagining futures of liberation. As Butler describes her own work, “I don’t write about good and evil. I write about people.”

I’ve had “Aliens” by Pisces Seeking stuck in my head for so long. It’s such a bubbly tune that makes a UFO invasion seem like a lot of fun. As the aliens take over their home, blasting music and eating all of their food along the way, this song is a silly, heartfelt consideration that these beings from outer space may not be so different from us after all.

There’s this phenomenal short story by Rita Chang-Eppig titled “The Last to Die.” Narrated for the Clarkesworld Magazine podcast, a woman made of glass appears on an island where humanity’s remaining mortals live out their final days. I love how this story reckons with death and elderly care, about memory and aging.

And, of course, Frances Forever’s viral hit, “Space Girl.” Such a cheerful, delightful song, it’s been floating around my brain since the summertime. I love their whimsical lyrics like, “Space Girl, the only way that we'd end / Was if you were sucked into a black hole.” It’s a whimsical alien babe love story that’ll leave you feeling starstruck.

If you're looking to learn more about science fiction and fantasy history in film, literature, and beyond, I highly recommend Imaginary Worlds. Each episode is a deep-dive into an element of SF/F, from big-budget franchises to behind-the-scenes creativity, and how it's shaped pop culture history. This show has a wonderfully massive scope, so there's definitely something for everyone if you're interested in special effects, design, anime, virtual reality, you name it. A few episodes I recommend starting with: the theremin’s haunting legacy, fascist imagery in fantasy, and an interview with Doug Jones, the actor famous for playing movie monsters.

LICK

Wong Kar-Wai’s 2046 is the third act in his trilogy, which also includes the classic In The Mood For Love and Days of Being Wild. Set in an unknown futuristic city, where many dream of taking the train to 2046 so they can be reunited with old loves. Haunted by that number, we encounter lovers getting into entangled affairs, searching for a nostalgic past in a city slick with chrome, neon, and bullet trains.

Martine Syms’s “The Mundane Afrofuturist Manifesto” is an empowering reconceptualization of Afrofuturistic media and writing, taking into account the many perspectives and experiences across the African diaspora. Syms is concerned with representation, and uses performance and video, as well as publishing platforms, to challenge racist stereotypes of and showcase the cultural power of self-transformation. Taking us from the lofty, escapist heights of sci-fi down to everyday existence, Syms writes, “The most likely future is one in which we only have ourselves and this planet."

If you want to get lost in a clickhole for hours, I highly suggest Landfill Edition’s 7th iteration of their Mould Map web comic series. This vibrant, interactive project features digital works from writers, artists, and cartoonists all centered around the theme of “pantropy” (where humans adapt their bodies to changing environments rather than the other way around). You can click through story panels, get lost in their index of comics, and watch as the boundaries and structures of the human body are completely upended through post-human digital interventions.

I came across the zine archive of Philly-based sci-fi collective Metropolarity and it’s been so inspiring in my personal voyage into speculative writing and criticism. Since then, I’ve kept up with founder M Téllez through their wonderfully weird newsletter, Despair Hope Despair. Born from a DIY approach to SF, Téllez and Metropolarity’s crew use futuristic storytelling to push back against colonialist and capitalistic systems, using language to reclaim power over their identities and shape world of resilience and communal care in the face of intersectional struggles of race, class, gender, and sexual orientation, making place within a genre that perpetuates these oppressions.

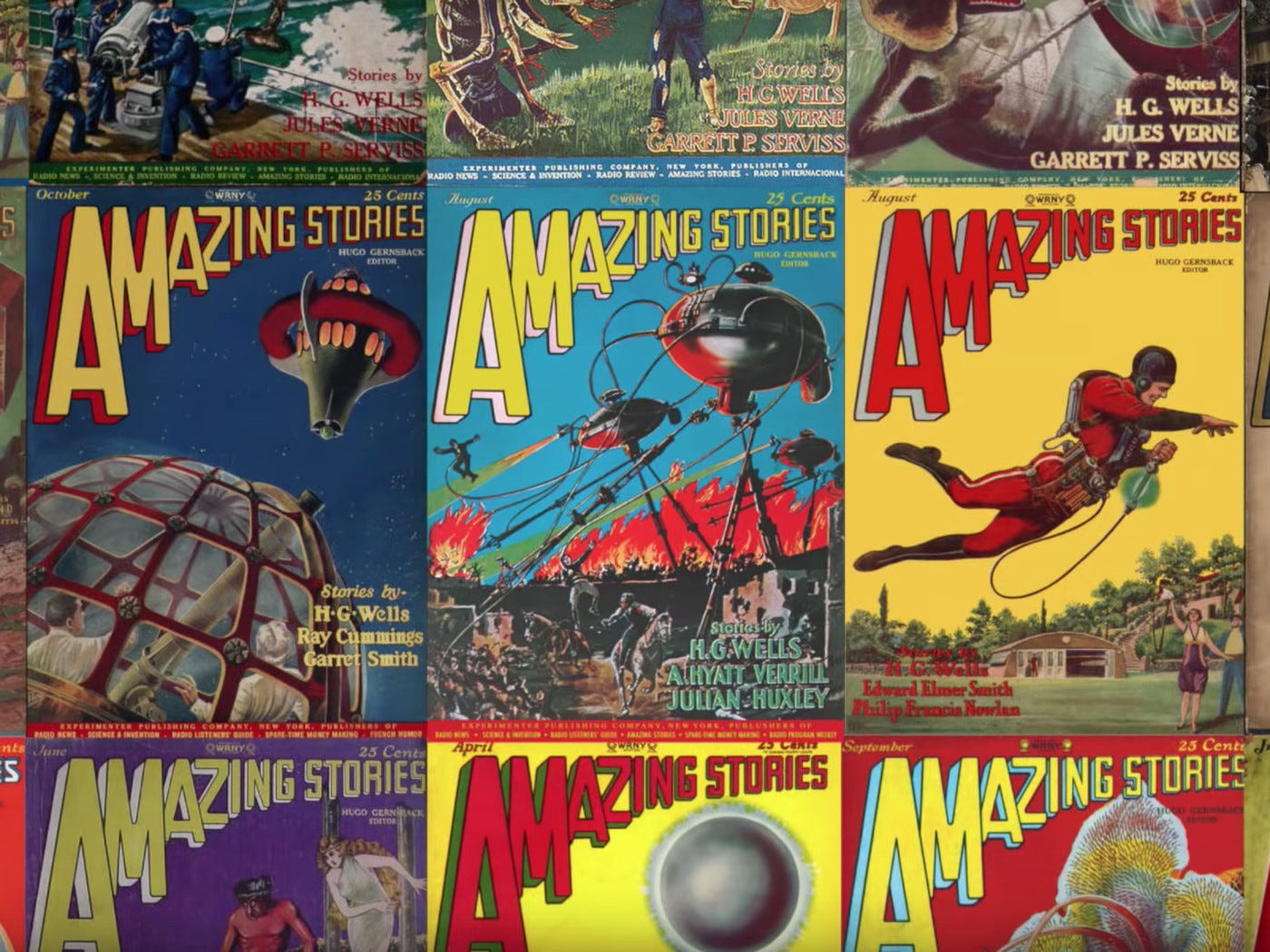

If you want to learn more about the history of science fiction book covers, I love this video that talks about the artists and publishers who developed the genre’s iconography. I can’t help but feeling like I’m in a literary art history course, looking at how the pulpy, popular mass-market paperback became a site of experimental design.

CLICK

“By Claw, By Hand, By Silent Speech” is a collaborative story between Elsa Sjunneson and Merc Fenn Wolfmoor. As a paleontologist comes into contact with a living dinosaur, she attempts to communicate in ASL. I’m embarrassed to admit this is one of the few SF stories I’ve read that not only centers a disabled character, but that character’s disability is not something monstrous or a hyper-mechanical enhancement. I love the way this story considers language, belonging, and human/animal bonds. They write: “When I decided to study paleontology…it was because the world of bones is silent. It was because the words that a dinosaur speaks are words that can be interpreted by brushes and metal picks, by observing curvature and decomposition, by noticing whether a skeleton was found in a tar pit or under a sand dune.”

If you’re interested in gaming, I’m sure you ended up playing (or at least heard about) Cyberpunk 2077 when it came out at the end of 2020. Despite 7 years of development, and a bungled release with delays and bugs, the game promised a slick, immersive sci-fi urban dystopia. Lars Schmeink’s analysis of Cyberpunk 2077 is a great piece of video game criticism, whether you’re familiar with CP2077 or not. Schmeink considers the subgenre’s historical limitations and how the game’s stylistic presentation of a gritty techno-fantasy risks perpetuating harmful stereotypes through its lack of political self-awareness—an ongoing issue in gaming communities as a whole.

Max Read’s essay, “In 2029, the Internet Will Make Us Act Like Medieval Peasants,” touches on a style of speculative writing oftentimes called “primitive futurism.” The premise is simple: we will progress so far into the future, that humanity will eventually regress into social collapse and or return back to archaic aesthetics. Although from 2019, Read’s points about digital ownership, data collection, rituals of behavior, and virtual labor remain relevant in today’s discussions of privacy and social media.

In his essay, “We’re Not in This Together,” Ajay Singh Chaudhary considers the imminent future of a world impacted by climate change. Chaudhary writes, “Climate change is not the apocalypse and it does not fall on all equally, or even, in at least a few senses, on everyone at all.” This may seem harsh, but it encompasses a few main issues that tend to get lost in our debates over solutions: inaction on climate change isn’t the result of individuals, but rather corporations and governments who make deliberate policy and economic choices, and that the harms of climate change will be distributed unequally across our society. Although Chaudhary’s work isn’t a literary piece of SF per se, this essay is a great political framework for inclusive speculative writing.

Facial recognition software and AI was once something only seen in movies. Now it’s a technology slowly being adopted by government agencies and companies to identify and track individuals. Heather Dewey-Hagborg’s “Sci-Fi Crime Drama With A Strong Black Lead” considers the racist history of eugenics that underpin our technological attempts to classify people. Forensic DNA Phenotyping attempts to use genetics as a kind of police sketch but this system, which is built on creating averages and datasets of probable appearance, fails to considers how categories, like race, are socially constructed. It’s fascinating to see how Dewey-Hagborg, a bio-hacker, takes a crack at these reconstructing processes through creative experimentation.

Thanks for taking the time to read! Feel free to share this little project of mine with your friends, lovers, and enemies. If you like what I do, you can help feed my leopard gecko through Ko-Fi or check out my website. You can find a list of books by the people I mentioned on Bookshop (I get a small commission through this and any affiliate links in this letter).

Until next time,

Ellie