031. Environmental Reliquary (I)

Divisions between the human and the earthly, manmade and natural—created oftentimes to plunder, exploit, and other—have proven to be delicate, finicky things, crumbling like soil between our fingers..

Hello friends,

Divisions between the human and the earthly, manmade and natural—created oftentimes to plunder, exploit, and other—have proven to be delicate, finicky things, crumbling like soil between our fingers when enforced. ‘Nature’ is not in some far-off place, away from our cities or our paved roads, it lives all around us, within our homes.

I’m sure all of you have spent Earth Day getting bombarded with social media infographics and green-washed marketing emails with questionable commitments to sustainability. One holiday a year never feels like enough, especially as our governments continue to fail us, communities local and global keep fighting to protect land from harmful economic interests and policies, and many of us are still impacted by volatile climates and polluted ecosystems.

I hope all of you spend a day this week somewhere out in nature—whatever that might mean to you. Now, more than ever, the social and the cultural is the ecological.

TOUCH

Adjua Gargi Nzinga Greaves’s poetic essay collection, Of Forests and of Farms: On Faculty and Failure, reckons with hierarchies of knowledge-building and reconnecting to wild landscapes as a Black woman caught up in harsh systems of oppression and assimilation, echoed in the controlling processes of agriculture. What happens when we reject this social violence of othering and categorization, and we re-educate ourselves within wilderness instead? Who do we become? “What I learned in the forest is to preserve special thinking / learn to protect all newness,” Greaves writes, finding resistance to alienation among plants.

One of my favorite places in New York is The Earth Room at 141 Wooster Street. Created by Minimalist land artist and sculptor Walter De Maria, this place has been occupied with soil since 1977. Every time I’m there, all I want to do is hop the glass barricade and walk across the soft dirt. It’s such a quiet space, one that invites contemplation despite the tourist-filled clamor of SoHo below. I wonder what The Earth Room’s keepers have found when tending to the soil, if they’ve found items people have thrown in there when the attendant wasn’t looking, if they’ve found some animal bones or something green sprouting from its depths.

Some of my favorite kinds of poetry books are pocket-sized. A mix of contemporary and classic writers, The Echoing Green: Poems of Fields, Meadows, and Grasses looks like it was made to accompany you on hikes, as you camp, or sitting snugly at the bottom of your bag as you wander around your neighborhood park trying to identify flora and fauna. I love how this anthology doesn’t try to clearly define what proper nature writing should be, but rather embrace the diversity of our experiences with greenery.

LOOK

Maria Theresa Alves’s ongoing project, Seeds of Change, considers how the legacy of slavery and colonialism has embedded into our landscape. Maritime routes between Europe, the Americas, and Africa, brought about a proliferation of “ballast flora” that, while dormant in the waste materials used to stabilize ships, eventually washed up and start to grow on shores after being dumped at ports. Previous iterations have included a floating garden in Bristol and raised beds in Brooklyn. Alves uses historical records to find, document, and even germinate these non-native species, while considering questions of migration and place-making. You can learn more about her work here.

I learned about Sarah Nicholls through a bookbinding workshop I took in January and I’ve been fascinated by her publishing practice ever since. Her linocut and letterpress pamphlets take you on environmental tours across New York City from the edges of Canarsie down to Red Hook and over to Jamaica Bay, discussing how human development and migration patterns have altered the landscape. No element of urban ecology is left unobserved: rising sea levels, the history of community gardens, and the lives of wildlife in our cities are meticulously, lovingly, documented.

Katie Holten’s Irish Tree Alphabet creates a series of letters based on the patterns of native and non-native tree species found around Ireland. Holten’s project is based in the Irish language’s predecessor: the Ogham alphabet, a medieval sequence of characters whose shape is likened to branches. As we continue to study the way forests communicate with each other, and see how manmade action moves plants and animals into new ecosystems and new adaptations to climate change, Holten’s symbols are a wonderful reminder that the way we we interact with one another is deeply rooted in, and actively shaped by, the environment around us.

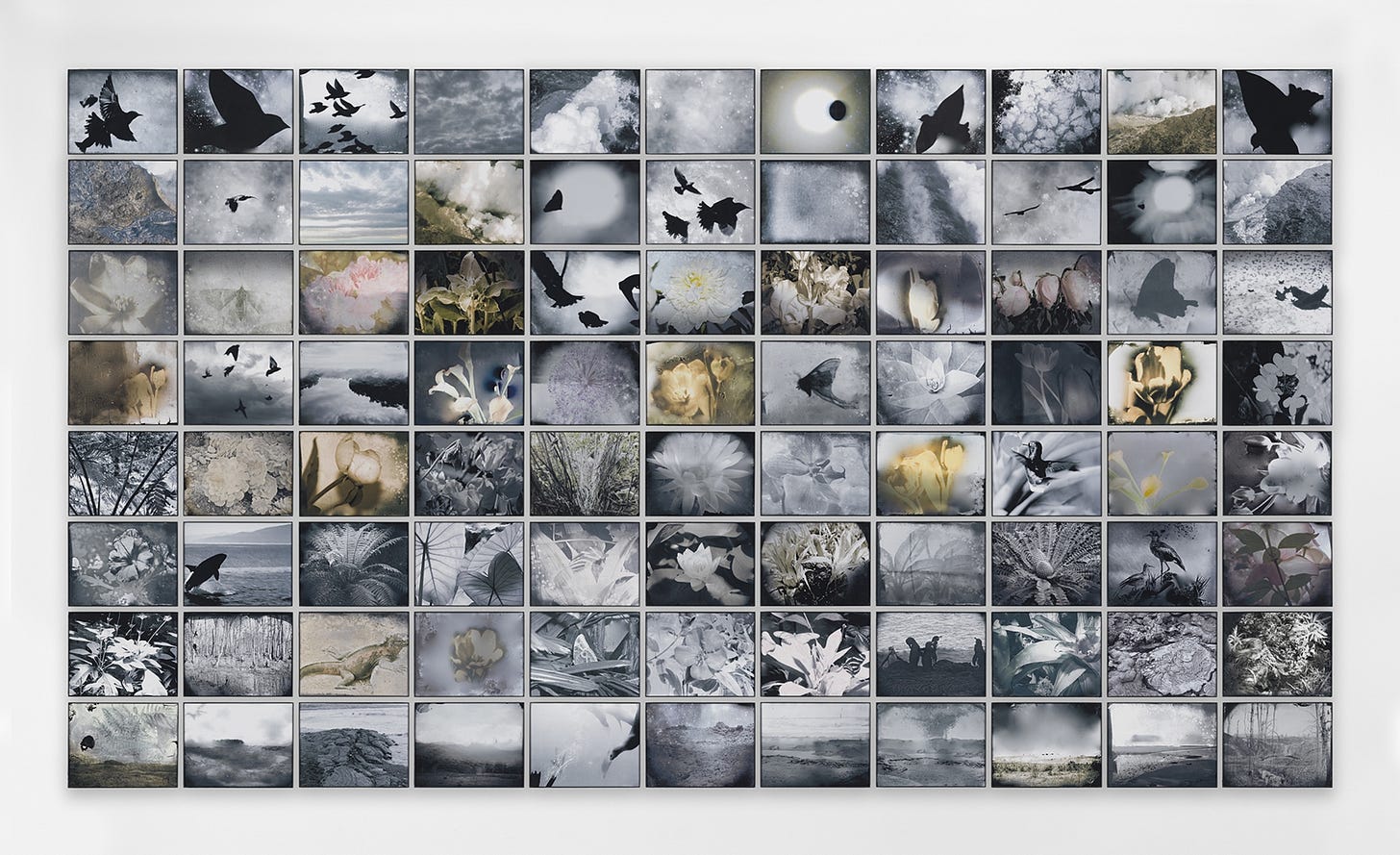

Since the 1960s, Michelle Stuart has used the land as muse and material. Fascinated with the many geological, botanical, and temporal scales of our planet, from the smallest of seeds and fragmented tools archeological sites to astronomy, Stuart's work has spanned sculpture, installation, earthwork, and, most recently, photography. I was particularly moved by her photographic suite, Flights of Time, from 2016. As so many of us find ourselves dislocated, I love how Stuart deliberately fragments celestial bodies, fluttered wings, blooming flowers, and images of animals across our oceans and forests at risk of manmade destruction, to create a vision of Earth’s complex history.

LISTEN

For The Wild has been one of the most instructive environmentally-focused podcast I’ve found over the years. A self-described “anthology of the Anthropocene,” this show features conversations with some today’s most innovative voices in ecocritical scholarship across art, science, and philosphy. Each episode is a wonderful primer to the intersecting environmental issues of our world from reparations for colonialist exploitation and nuclear waste to seeds as a tool for knowledge-building and cultural teaching, as well as considerations of our food and waste systems.

The Memory Palace has made a name for themselves in the audio community for their experimental approach to curious anecdotes of long-forgotten, minor histories. Their episode “Snakes!” about the appearance of cobras in Springfield, Missouri is no exception.

I’ve adored HumaNature’s thoughtful storytelling since I first heard their episode, “Hoofprints On The Heart.” Their adventurous tales of wandering travelers and encounters with the wild are also profound personal reflections on identity, home, and the ways in which we live. Whether or not you consider yourself to be an outdoors-y person, you’re sure to get immersed.

When we think of the sounds of nature, bird calls or the rustling of leaves in the wind usually come to mind. But what about the creatures living on a scale smaller than our eyes and ears can comprehend? Zimoun’s sound-sculpture, 25 woodworms, wood, microphone, sound system, gets up close and personal.

Discussions about climate change can leave you feeling overwhelmed and powerless. How To Save a Planet, takes an in-depth look at the biggest issues, impending challenges, and hotly-debated solutions in modern environmental policy and activism. Episodes about the real estate boom in parts of Miami prone to flooding, the struggle to ‘green’ buildings, and the life of a kelp farmer may leave you hopeful or frustrated, but extremely informed nonetheless.

LICK

By now, you’ve probably seen Atmos’s slick, eye-catching editorials and graphics all over Instagram. Atmos feels like something more than just a socially-engaged environmental magazine. With immersive profiles of activists, ecopoetry, and investigative pieces (like how the booming weed industry should focus on sustainable farming practices), we see how culture intersects with nature and how economic and social struggles are intwined with our local ecologies. Our ability to educate and tell stories about our land, what we eat, the species we encounter, paves the way for a unified fight for environmental change that centers diversity.

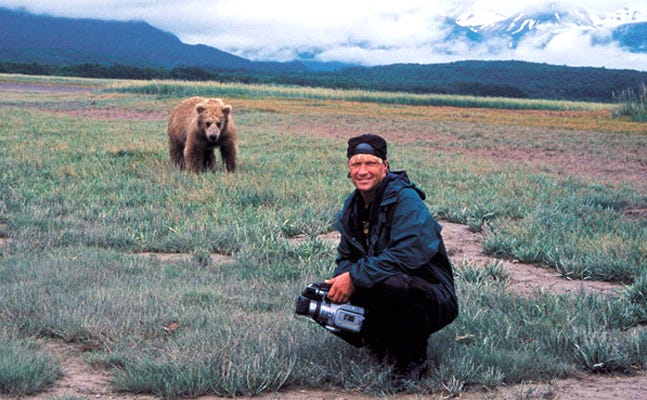

Werner Herzog’s 2005 documentary Grizzly Man is one of those movies you see once and then you remain haunted by its peculiar darkness. Herzog traces the life of Timothy Treadwell as he camped out in Alaska’s Katmai National Park and attempted to befriend the local bear population. Much of Herzog’s footage comes from Treadwell himself, who would frequently bring a camera on his trips to document his encounters. What is initially a heartwarming tale about a man who loves bears quickly becomes a cautionary tale of respecting wildlife. Knowing that Treadwell and his girlfriend were brutally mauled and eaten in 2003 makes the documentary chilling to watch, especially we see Treadwell’s enthusiastic attempts to engage with these bears he thought “trusted” him. You can’t help but think that, as much as we try to understand and ascribe our beliefs to nature, it remains dangerously unknowable.

Scientific documentation has become the primary tools we, as a society, have come to understand the plants and animals around us. Jan Švankmajer’s 1967 short film, Historia Naturae, Suita, is a whimsical, animated collage of illustrations, prints, and real specimens that replicates biological systems of classification and evolutionary history.

If you’re looking to keep up with the work of climate activists in the South, Southerly is a great resource. While we oftentimes think of Northern factories and industries as big sources of pollution, some of the worst environmental racism and classism in the country are found across the South thanks to lax regulations of big corporations and long, toxic histories of resource extraction and local exploitation. Southerly’s reporting covers the work of community organizers (especially in poor and communities of color), the impacts of and rebuilding after natural disasters, and showcases empowering movements towards sustainable agriculture and land remediation with a strong emphasis on Southern culture and history.

CLICK

On this day, I can’t help but revisit NPR’s explosive report about the oil industry’s decades-long deception about plastic’s recyclability. An overwhelming majority of the plastic we consume, even if we clean it and sort it properly, ends up either buried in landfills or shipped to countries where it sits and rots with nowhere to go. Rather than spending the time and money to develop technologies to break down these materials, oil companies sponsored ‘educational’ campaigns to cleanse their public image through false promises of sustainability. Now, the various types of plastics we use to produce goods have out-paced what limited recycling tech there is, leaving only expensive machinery that is extremely limited in what it can process, while pollutants continue to build up in our land and spill into our water systems.

Harmony Holiday’s "Spectacular Herbs” essays for BOMB Magazine are poetic contemplations on the socio-cultural histories of plants used to nourish, feed, and care for ourselves. Whether it’s the way kelp acts as a dual symbol of medicine and toxicity or how wild lettuce offers resilience in the painful wake of anti-Black violence and cloves are emblematic of toxic masculinity, the entire archive is worth reading.

How does our mass surveillance of wildlife impact the way we understand ecosystems? Steph Yin contemplates the rise of digital tracking technologies in her essay, “Inside the Animal Internet.” Attachable GPS devices, livestreams, and apps that allow you track and log plant and animal data continue to grow in popularity among academic researchers and citizen scientists alike. While these technologies bring new opportunities for understanding the interconnected relationships in local and global ecologies, especially among endangered wildlife, this unprecedented level of access may impact how we think of the environment in relation to ourselves. As Yin notes, “digital engagement with animals also gets entangled in human narratives.” There’s a temptation to impose human relationships, value systems, and emotions onto non-human beings who don’t think and communicate as we do. How can these tools of understanding become meaningful action for conservation, not just viral fascination?

In 2015, Michele Scott penned this poignant essay about creating a covert garden at her prison for The Marshall Project. The violence of mass incarceration oftentimes presents itself through a forced sterility: concrete and metal buildings, confiscated items that may have personal and cultural value, regimented schedules. Even in this bleak monotony, Michele finds solace in the careful tending to plants and soil and in the time spent researching how to sprout greenery in this harsh place. Scott writes, “Gardening was a distraction, a kind of half-freedom from the constant loop always sounding in my thoughts.”

Bianca Stone’s poem, “Nature,” pokes playful holes in humanity’s self-fashioned divine narratives of superiority and control over nature. I love how the poem opens: “Maybe humans are the failed A.I. of Nature. / Maybe Nature made something it thought would tend the garden.” While Stone’s last line hits like a punch to the gut.

Thanks for taking the time to read! Feel free to share this little project of mine with your friends, lovers, and enemies. If you like what I do, you can help feed my leopard gecko through Ko-Fi or check out my website. You can find a list of books by the people I mentioned on Bookshop (I get a small commission through this and any affiliate links in this letter).

Until next time,

Ellie