033. Concealed Reliquary

Hito Steyrel’s 2013 video, How Not To Be Seen: A Fucking Didactic Educational .MOV File, outlines 5 ways to hide yourself: 1. Make something invisible for a camera, 2. Be invisible in plain sight...

Hello friends,

Hito Steyrel’s 2013 video, How Not To Be Seen: A Fucking Didactic Educational .MOV File, outlines five ways to hide yourself: 1. Make something invisible for a camera, 2. Be invisible in plain sight, 3. Become invisible by becoming a picture, 4. Be invisible by disappearing, and 5. Become invisible by merging into a world made of pictures.

To be invisible (or rendered invisible by others), is a complex thing. Acts of concealment can be informed by political systems and structures of power, can be the product of personal comfort or insecurity, a secret kept out of shame or to respect the wishes of another, and sometimes the reveal can be as painful as it is a relief. For this letter, I decided to take a look at stories of the lost and the forgotten, the once unknown, what happens when the actions of others are kept out of sight, and when secrets fail to stay buried.

TOUCH

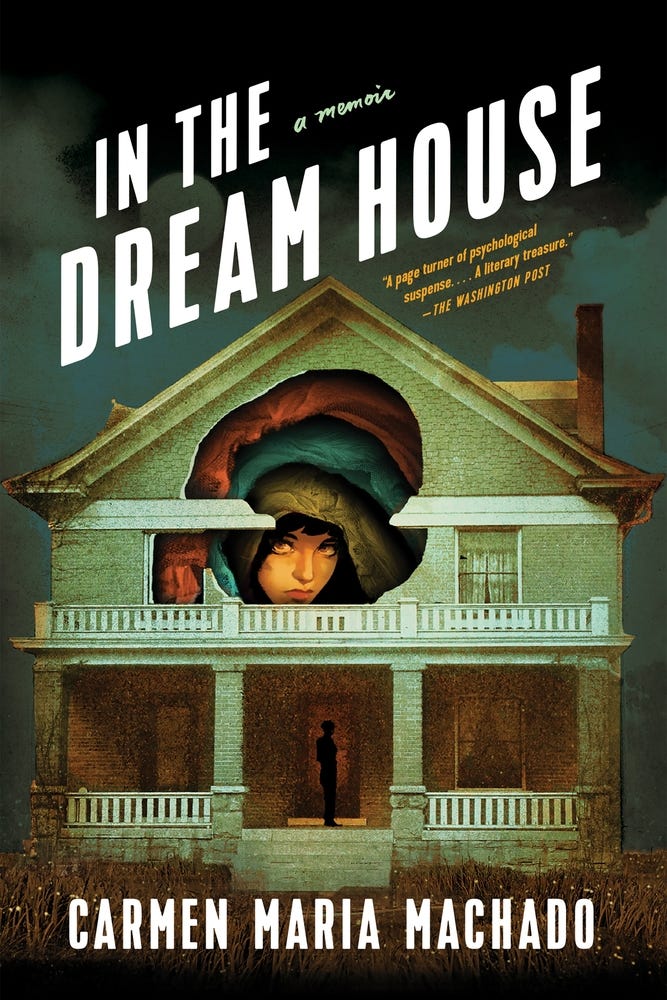

I’m trying to imagine all of the ways I can describe Carmen Maria Machado’s In The Dream House, but none of them are good enough. A memoir unlike anything I’ve ever read, Machado recounts one of the darkest periods of her life—her multi-year abusive relationship with her ex-girlfriend—through haunting prose interwoven with folklore and fairytales. Machado taps into so much of what is left unspoken and unseen from the way lesbian victims of domestic violence are overlooked by criminal justice systems and within queer communities to the insidious, isolating nature of DV itself, the masking of pain and violence from her friends, the outside world, and herself.

LOOK

Titus Kaphar’s portrait series, From A Tropical Space, reckons with the overlooked anxieties and struggles of Black motherhood. Whether its the threat of violence or fear of social precarity, Kaphar makes this known through voids in the canvas, outlined bodies of where children should be. Take “The Aftermath” (2020) where his subject casts her gaze out across the front of her house. What is supposed to appear like the American dream (a house, kids, a car) has been devastated by unseen forces. There is so little Kaphar tells us about the mothers in his paintings, leaving symbols embedded in each composition for us to speculate on each woman’s inner life, as they embrace the empty spaces of their children with intimate gestures of protection and care.

Photographer and performer Liu Bolin has made a name for himself as a master of camouflage. Each image is an exercise in disappearing as Bolin paints his body to blend into the everyday landscapes of Beijing, embed himself into landmarks and famous art historical works like the Wall Street Bull and Picasso’s Guernica, and traverse cities around the world for his series, Hidden in the City. Dubbed the “Invisible Man,” Bolin’s work considers national identity and what it means to be an outsider in his own home, informed by his clashes with the Chinese government who evicted him and destroyed his studio back in 2005. Since then, Bolin has travelled across the country and abroad, exploring the cultural and political constructions of societies and documenting sites of economic power and consumption. Every photograph feels like an act of contemplation on what it means to belong in an ever-changing world.

If you’ve ever visited a museum with a medieval art collection, you’ve probably encountered a reliquary in its galleries. Reliquaries are some of my favorite religious artifacts for the way these vessels were meticulously crafted to elevate the holiness stored within. The blood and bones of saints, as well as objects of Biblical significance, were encased in luxurious metals and jewels, offering pious churchgoers and pilgrims the smallest glimpses of relics through panes of glass and openings in the structure (or like this bust of St. Barbara, almost none). For all of their sacred protection, these containers have had their fair share of fraudulence and forgery since the medieval age, with the authenticity of remains still questioned and exposed to this day.

While we oftentimes take maps for granted as accurate, precise representations of the world, these geographic depictions can act as reflections of social transformations and geopolitical conflict both through what they reveal and what they omit, or just be downright inaccurate. Going as far back as the 1950s, cartographers for the Swiss Federal Office of Topography have been playing a kind of mapmaker’s joke by inserting illustrations of people and animals into their geographic renderings. These subtle drawings have gone unnoticed years, sometimes decades, in playful defiance of Swisstopo’s emphasis on precision and accuracy. Swisstopo’s response to the ongoing prank? “Creativity has no place on these maps.”

LISTEN

I’ve been thinking about White Lies since it first came out in 2019, all throughout last summer’s protests and now as fights for racial justice and historical reckoning continue on the streets and in government buildings. At the heart of this podcast is the 1965 murder of white minister James Reeb who was brutally beaten with two other ministers for their participation in the civil rights march in Selma, Alabama. To this day, his death remains unsolved, with a jury acquitting his attackers and white townsfolk claiming conspiracies that his fellow ministers killed him to make him a martyr of the civil rights movement. I can’t emphasize the thoroughness of this investigation enough. Each investigator and witness involved in the initial case and linked to the original suspects are all under scrutiny. With a deep respect and awareness of how so many lynchings and similar acts of racist violence remain unsolved today, no hard question is left unasked and no lie left un-confronted to expose the lengths people will go to mask generations of hatred.

As the horrific mass graves of Indigenous children continue to be found in Canada, and with the U.S. government beginning its own investigation into the genocidal actions fo residential schools, Connie Walker’s interview with Longform feels especially timely. One of the few Indigenous investigative reporters for CBC, Walker is responsible for some of the most powerful audio pieces sharing the marginalized stories and traumatic experiences of Indigenous communities (particularly women) across North America, including Stolen: The Search for Jermain and the series Missing & Murdered. To hear Walker recount her experience trying to get her supervisors and media organizations to pay attention to these dark histories and concerning trends of violence against Indigenous people is a reminder that no matter how much we try to forget and hide the awful past, there will always be a reckoning.

LICK

I first learned about the “concealed shoes” phenomenon from a TikTok of a young couple who made the discovery when they began remodeling their English home. Many concealed shoes discovered today appear to be from the 19th century and earlier, although there is no consensus on why people would hide cloth, leather, wooden, and rubber shoes into the structures of buildings. The predominant theory is that the shoes were a superstitious charm meant to promote fertility and protect families from evil. In 2012, the Concealed Shoes Index was created and, now managed by the Northampton Museum, contains over 1900 reports and collected shoes.

FOIA The Dead is a fascinating exercise in government transparency and the continuation of bureaucracy that surround the dead. Every time an obituary is published in The New York Times, their team files a Freedom of Information Act request to see what the secret files the FBI had complied about them over the years. Equal parts unexpected and terrifying, their digital archive (which ends around 2019) is fascinating to sift through.

I really enjoyed reading this interview between theorist Lukáš Likavčan and historian Sofia Irene about the political nature and historical trajectory of face masks from last April. Spanning survivalism-inspired runways and vulnerable semiotics, their discussion still rings true today. Irene notes, “Yet, whether we talk about responsibility or solidarity, we can still see how the mask approximates a function of a shelter, or even better a shell. Both imply a defense, a closing off, going in.”

CLICK

Lucille Clifton’s poem “the lost women” sinks its teeth into a painful truth of our history: the lives and legacies of women who have been erased and forgotten. As academics, writers, historians, community members attempt to canonize, bring these women and their stories to light, you can’t help but wonder who is missing. One line, in particular, hit home: “after a hard game to chew the fat / what would we have called each other laughing / joking into our beer?”

In 1962, the coal-laden earth of Centralia, Pennsylvania caught on fire and has continued to blaze ever since. Emily Harnett’s piece for The Baffler wrestles with this town’s forgotten history and how this once-hopeful place for the coal boom has become overgrown and lost to time by its former residents and the nation alike, a hidden fire still eating away at its insides.

Rebecca Lindberg’s poem, “In The Museum of Lost Objects,” is a slow accumulation of the secret histories tucked inside the things we take with us throughout our lives. From treasures from past plunders to a missing set of bones that once belonged to an impress, the mighty weight of history grows in absence.

The revelation that social media oftentimes masks one’s reality is nothing new, but I do appreciate Tatum Dooley’s take on the subject in her essay, “The Cost of Simplicity.” Dooley focuses on today’s influencers and how many of them attempt to perpetuate an aestheticized image of minimalism despite the never-ending cycles of consumption that fuel their digital popularity. Entangled in the term’s art historical significance and today’s branded design and marketing languages of beauty, Dooley writes of the ‘lifestyle’ industry, “Minimalism, or pseudo-minimalism, turns out to be a handy undercover vehicle for consumer obsession: aesthetically pleasurable, and suggestive of high-minded austerity, it obscures its own extravagance.”

I’m sure all of you have, by now, read about the house found in upstate New York that was originally made by architect Gregory Ain for a 1950 MoMA exhibition of modernist residential design. Once placed on the rooftop of the museum, the “Exhibition House” was relocated to Croton-on-Hudson and the model forgotten after it served its purpose. Thanks to the sleuthing of a modernist home historian, it was finally relocated a few months ago after hiding in plain sight, both in the neighborhood and in the MoMA archives, for so long.

I will end with one more poem, this time by Chiwan Choi. Titled “portraits and erasures,” the poem begins with the author’s act of concealment: “so i pick up a pencil and begin to erase myself.” As he reckons with the cruelties and challenges of immigration, the agony of illness, to live and die away from family in a foreign land, one image spills into another, simultaneously obscuring and revealing. Choi contemplates, “there are borders to cross / there are borders not meant to cross.”

Thanks for taking the time to read! Feel free to share this little project of mine with your friends, lovers, and enemies. If you like what I do, you can help feed my leopard gecko through Ko-Fi or check out my website. You can find a list of books by the people I mentioned on Bookshop (I get a small commission through this and any affiliate links in this letter).

Until next time,

Ellie