41. Toxic Reliquary

It’s been meme’d to death already: that troubling study that says we might be consuming about a credit card’s weight in microplastics each week...

It’s been meme’d to death already: that troubling study that says we might be consuming about a credit card’s weight in microplastics each week, paired with that grim report that scientists have found plastics in human blood and in our lungs. Every time I see one of those TikToks about eating microplastics or cursed videos of people dumping glitter into their body products or foods, I’m reminded of seeing those photographs of dead birds cut open and all of the plastic they ingested over their lifetime spilling out of them like a pool of organs.

April has started to become Earth Month, no longer just Earth Day, with greenwashed corporate marketing campaigns kicking off earlier and earlier every year and more protests and disruptive actions taking place with greater frequency. I’ve experienced a lot of mixed feelings about this time, perhaps more than any other year so far. As hard as I try to parse and articulate my relationship to climate activism in the current moment—this jumble of frustration, rage, hope, and determination—I keep coming back to the “plastiglomerate” with its fossilized multi-materialisms and intersecting timescales, a peculiar byproduct of peculiar times.

As this month comes to an end, I wanted to use this newsletter to reflect on what still lingers, what haunts us with its rot and off-gassing, what still stains and sicks our bodies and the world around us, to think about what work still needs to be done.

TOUCH

Joyelle McSweeney’s Toxicon and Arachne is a poetry collection in two parts: first written during her pregnancy, then after the brief life and death of her daughter, Arachne shortly after birth. The body becomes a permeable membrane, contaminated with grief, corrosives, and remnants of the techno-industrial age. McSweeney’s polluted poetics traverse the physical and metaphysical worlds, turning our everyday experiences with waste materials into inescapable moments of uncanniness punctured by textured sonic lyricism. What comes after catastrophe? As McSweeney writes, “Here life converts its currency: protein raincoat: dollar bill: kill floor: T-cell: chemical spill: gyre: fire bred to sink its tooth in bone and breed its own accelerant…”

I first encountered Patricia Domínguez’s work as an artist and experimental ethnobotanist at the New Museum, as part of their “Screens Series.” Colored with neon LEDs and textured soundscapes, I was particularly struck by her video piece, La balada de las sirenas secas (2020). Domínguez’s film considers the way landscapes have been transformed by corporate intervention. Done in collaboration with Las Viudas del Agua, a local female-led organization fighting for access to water in their communities, Domínguez uses fantastical science-fiction storytelling to speak about the ways the Petorca region of Chile has been impacted by the diversion of water large-scale agriculture in the area, leaving local residents and wildlife to suffer from droughts, sickness from a lack of clean water for drinking and sanitation. Even as corporate avocado plantations flourish, wasteland and death grows in their wake.

Words can’t describe the extent to which Evelyn Reilly’s Styrofoam has impacted my own ecopoetic practice. Described as “applied poetics” by one critic, Reilly’s poems entangle reflections of the body with pollutive language of plastic’s chemical structures, images of roadkill, punctuated interplays of scientific nomenclatures. The poem becomes experiment, infinitely fragmenting and mutating and foaming across (un)natural landscapes. Take the poem “Permeable Mutual Diagram” where she opens with the line: “in the polysmell / of the inverse.garden.”

LOOK

I can’t stop looking at Dasha Plesen’s bacterial beauties. These chromatic spreads are so gorgeously moldy, and really showcase the creative and scientific power of bio art’s experimental mediums. If only the leftovers I forget in my fridge looked this pretty.

I would be remiss if I didn’t mention Mary Mattingly. An ecofeminist multimedia artist, Mattingly’s works are speculations on nomadic futures spurred by the collapse of civilization, and the improvised creations that come about from the need to adapt to a changing planet while living in the wreckage of consumption. I'm thinking about two works of hers from 2013 House and Universe series: Life of Objects (pictured above) and Pull. Both pieces feature this massive, rock-like bundle comprised of Mattingly's own personal possessions, tied together to form a mass that Mattingly moved around with Sisyphean exertion. Cycles of production and consumption become intertwined through this lumped-together archive of one's material existence.

Chloe Dewe Mathews's photographs are rich explorations of humanity's relationship to natural resources. Back in 2018, Mathews published a series of images taken during a trip across the landscapes of Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Iran, Turkmenistan, and Russia along the coast of the Caspian Sea. These places have complicated relationships to the extraction of resources like oil and uranium. This series bring us to spas where bathers sit in oil or soak in waters made from radioactive building materials. Oftentimes, we see open-air fires, oftentimes sparked by objects like cigarettes coming into contact with pockets of natural gas that seem to burn endlessly (like the burning pit pictured above, found on the side of a road).

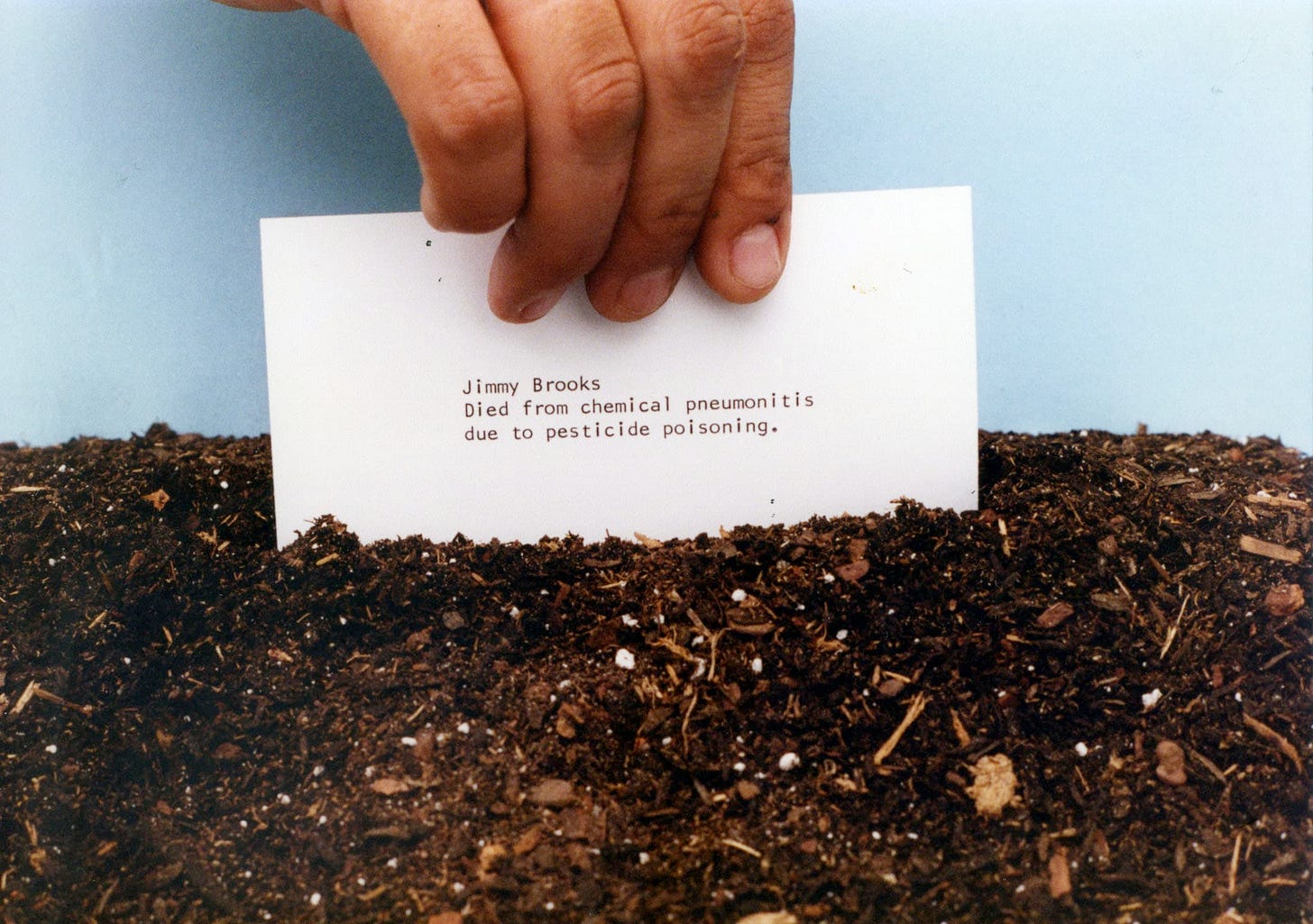

We usually don't give a second thought to the labor that goes into growing and bringing food to our grocery stores. Although Black and Chicano farm workers have had a long, rich history of organizing for better working conditions in the United States, many continue to suffer the impacts of dangerous workplaces and harmful industrial farming practices. Christina Fernandez's installation Untitled Farmworker (1989/1994/2020) shares the experiences of agricultural workers through a series of notecards planted like seeds into a mound of soil. The cards name a laborer along with any injuries, illness, or death that happened as a result of their job. Replicating the typewritten format of bureaucracy, this collection of cards grows into a powerful inditement of political injustice within American agriculture.

LISTEN

A self-described “true-crime podcast about climate change,” Drilled takes a deep dive into the fossil fuel industry’s ongoing role in the climate crisis from avoiding accountability for pollution to spreading blatant lines and misinformation. Host Amy Westervelt and her team’s tenacious reporting is so critical in this moment when we’re reevaluating our economic relationships to these harmful energy sources. I don’t think this brief description will do the scope of their work justice, so just go listen.

While we talk much more frankly about the dangers of plastic waste and the struggles to recycle this pollutive material now, that hasn’t always been the case. BBC Radio 4’s show Seriously… published this great episode about the history of plastic last year, in tandem with an exhibition at the V&A. Plastic has become such a normal part of our lives now, so it is fascinating to hear about its invention and how the material has transformed to meet human consumption over the years. As we work together to find new alternatives and navigate the consequences of its use, this history is critical.

The United States military is one of the single largest polluters in the world. If it were its own country, it would be the 47th largest emitter of greenhouse gases, ranking higher than countries like New Zealand, Morocco, and Finland. Not only have the lands and people who have been subjected to military action suffered (like bombings and nuclear testing), but active duty soldiers as well. WBUR’s On Point recently published a report about the military’s use of “burn pits” to dispose of waste during the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. While the military claims that this was due to a lack of waste disposal infrastructure in the area, these pits would emit toxic chemicals as they burned equipment, paint, medical supplies, and sometimes even cars and batteries. Soldiers, who breathed in the smoke without any protection, came home with long-term lung damage and cancer. To make matters worse, the VA continues to deny requests for medical treatment coverage resulting from pit exposure.

LICK

Safe is one of those movies that's haunted me since I first watched it a few years ago. Set in suburbia, a housewife finds herself succumbing to an unknown environmental illness, becoming increasingly sensitive to chemical products like perm solutions and aerosols. I could devote a whole newsletter to unpacking all of the little nuances and details of this movie, like its highly sterile, plastic-laden interiors, the way it pokes holes through perfect image of white suburbia, and the history of medical establishments disregarding women's health concerns.

I’ve become intrigued with Trash Club since I first saw the organization present their work as part of a New Inc. incubator event. Based in New York City, Trash Club is a community-driven platform that is actively investigating and creatively engaging with the city’s waste management systems and polluted ecosystems. Driven by a research fascination of our trash’s history and how local ecologies are impacted, one of Trash Club’s recent projects explored the New Jersey Meadowlands, a site with a long history of pollution and now the site of environmental restoration and renewal.

I recently thought back on this peculiar phenomenon that emerged in mid-2000s beauty: anti-pollution skincare. I’ll be honest, I totally fell for the marketing of Clinique’s Hydrating Jelly, which promised “hydration repair plus pollution protection.” As we stress about things like emissions and air quality, and how that might be impacting our long-term health, anti-pollution beauty reflected those very anxieties of toxicity, even when the science was still divided over the usefulness of such a label. Now, the idea of “clean beauty” has stepped into its place, once again asserting a certain privilege of ingredient purity not readily accessible (and still wrought with its fair share of green-washed, dubious claims).

Behemoth (2015) is a documentary that takes us into the coal mines of Inner Mongolia, bearing witness to the daily lives of ash-heavy and sweat-soaked coal and iron miners. This area first caught the attention of director Zhao Liang when he saw the region’s thick blanket of smog on a satellite map. The film itself is a meditation on who bears the cost of China’s rapid industrialization and need for coal consumption. Workers are driven to the brink of exhaustion, breathing in toxic dust as they are driven deeper into ecological destruction in the name of economic growth. Juxtapositions are jarring: sweltering faces are illuminated by furnaces and dust clouds bloom into the air in one scene, while oblivious sheep graze on a patch of grassland in the next.

CLICK

There’s something about C. K. Williams’s poem, “Tar,” that lingers in the corners of your mind long after read it. This threat of an encroaching danger (in Williams’s world the unknown future of Three Mile Island) permeates the spaces between his lines, inescapable even in the quiet of suburbia. Not only do we have this potential radioactive contamination, but the smoking stench of hot tar and torn out pieces of asbestos bringing this potentially lethal menace closer to home.

While we’re on the subject of nuclear threats, I recently revisited Emma Claire Foley’s essay, “Nuclear Renewal.” In this piece, Foley, who works as a policy researcher to reduce threats of nuclear weapons and war, contemplates the decision of the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory to upload footage of nuclear bomb tests from the 1940s to the 1960s on Youtube and what it means to have access to this archive in our own modern day full of its own anxieties of war and destruction. What I appreciate most about Foley’s analysis is her observation of the tests’ seeming containment, how far away their devastating mushroom clouds seem to viewers, yet traces of these tests live on: “according to the CDC, small amounts of radioactive materials can be found in the bodies of anyone living in the United States since 1951.”

It feels like every day now brings a new horrifying discovery of brutality across Ukraine, from civilian deaths to senselessly ravaged cities. While the environmental impacts of war has been a subject of study for decades now, I wanted to share this particularly troubling story by Emily Anthes about how the ongoing war in Ukraine is threatening the country’s ecosystems. The Black Sea Biosphere Reserve, which is currently under Russian occupation, is in particular danger having been a safe haven for migratory birds, endangered species of mole rat and dolphin, and numerous species of sea creatures. Anthes’s story is essential reading, not only about the current condition of Ukraine’s landscapes fraught with fires and bombings, but about the much larger history of human impact on the environment through destructive war.

You should avoid Charles Baudelaire’s poem “A Carcass” if you are easily queasy. Mapping out the processes of rotting flesh, the poem is a nauseating feast of the senses, a decaying cocktail of sights and smells where the cycles of life and death become entangled across the gravesite. Baudelaire writes, “And the sky cast an eye on this marvellous meat / As over the flowers in bloom.”

Thanks for taking the time to read! Feel free to share this little project of mine with your friends, lovers, and enemies. If you like what I do, you can help feed my leopard gecko through Ko-Fi or check out my website to find more of my writing. You can find a list of books by the people I mentioned on Bookshop (I get a small commission through this and any other affiliate links in this letter).

Until next time,

Ellie