49. Culinary Reliquary (II)

Here’s my last newsletter of 2022. I hope it leaves you hungry for more.

Hello friends,

In 1975, Martha Rosler begins her performance of Semiotics of the Kitchen by introducing the appliances around her. Following the alphabet, she says their names out loud, followed by a violent demonstration of their functions. A work of conceptual feminist art, Rosler challenges the notion of the cheerful, eager to serve hostess, instead letting her frustration out on the medley of tools associated with the confines of domestic life. That same year, Chantel Akerman released her film, Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles. The movie follows a widowed mother through her rigid schedule of chores, with long continuous shots as she goes through the daily tedium of preparing meals in yolk yellow kitchen. Like Rosler’s performance, we watch Dielman from across her kitchen table as if we’re the audience of a cooking show, uneasy with anticipation that something will go terribly wrong.

As we continue with last month’s theme, I’m thinking about cooking as ritual and routine. As we gather with friends and family for the holidays, the kitchen becomes a place where traditional recipes are revisited, favorite meals are made, and late night snacks are sneakily consumed. Food is a way of sharing stories and making memories.

So here’s my last newsletter of 2022. I hope it leaves you hungry for more.

TOUCH

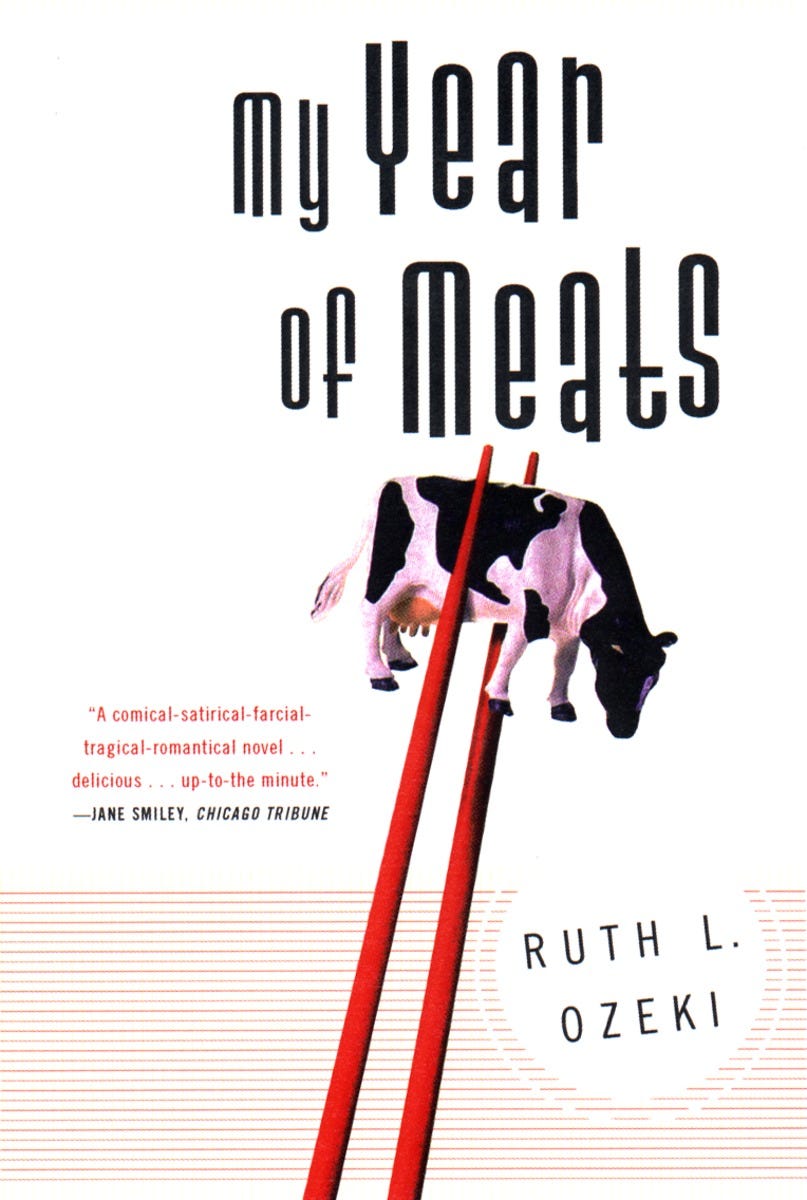

Ruth Ozeki’s My Year of Meats is a strange read, one that still haunts me from time to time. The book follows a Japanese documentary filmmaker who’s hired to produce a show about American meat businesses. She soon becomes caught up in a world of industrial agriculture, toxic growth hormones, and women navigating this state of hyper-consumption. At a time when we’re so far removed from the labor that goes into growing our food, My Year of Meats invites contemplation. It’s crazy to think that book was published in 1998, predating the national conversations about the health and environmental impacts of factory farming we see today.

When I decide to embark on the occasional adventure in baking, I love using Food52’s Five Two Apron to stay clean. I actually gifted this to my boyfriend a few years back because of how well-designed it is, and I keep borrowing it for myself. The apron is super adjustable, with lots of pockets to store utensils and glasses. It even has a little conversion chart sewn into its lining and the bottom corners of the apron have extra padding to double as pot holders. A practical essential for your home kitchen.

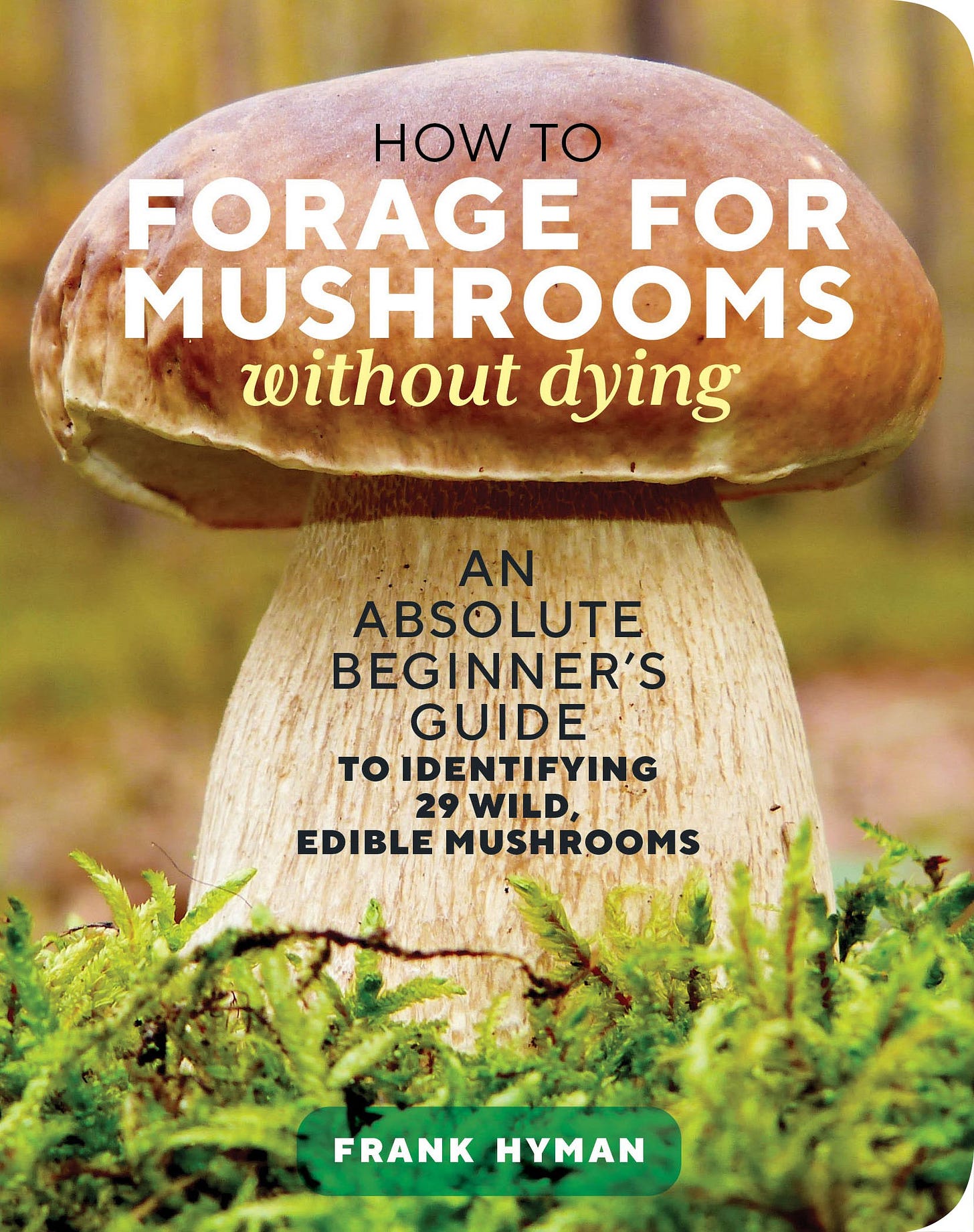

Last year, I was gifted a copy of Frank Hyman’s How To Forage For Mushrooms Without Dying. Don’t let the funny title fool you, this is a thorough, serious guidebook to wild edible mushrooms for novices and experts alike. Hyman emphasizes safe practices, and includes common toxic species for you to compare. I also love that, in addition to giving information about mushrooms’ flavors and their common names (in case you look for them at a farmer’s market or a grocery store instead of the woods), he also includes best practices for preparing each one for eating.

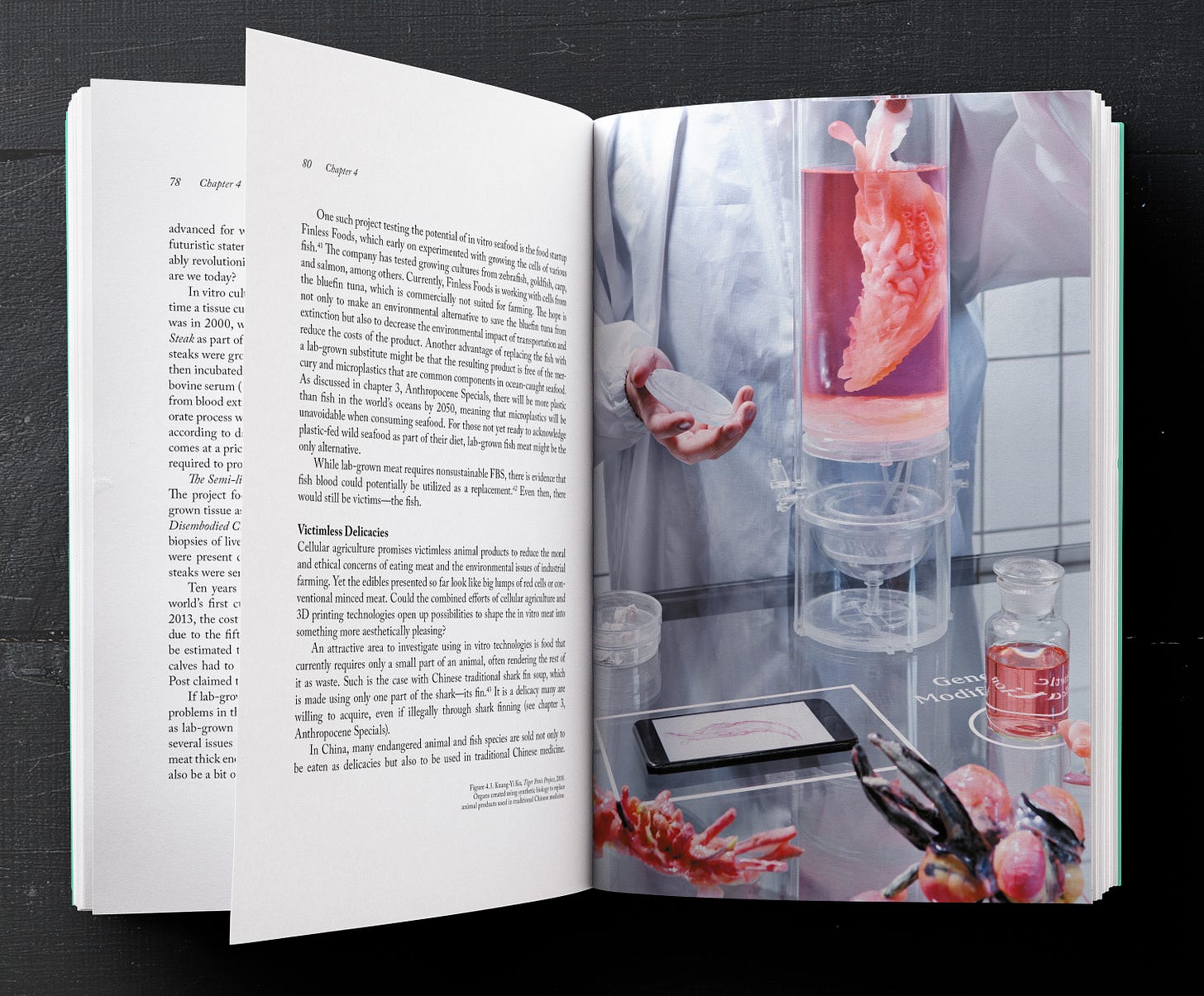

The Anthropocene Cookbook is a collection of speculative food projects inspired by the disastrous impacts of the climate crisis. Each of these science-fictional recipes offer creative adaptations to traditional food practices that will become disrupted by environmental change. The edible futures presented here are fascinating, strange, and, honestly, a little nauseating (like ingredients sourced from plastic and sewage, or dairy products made with human bacteria and breastmilk). The Anthropocene Cookbook’s recipes are lessons in survival, hybridity, and experimentation.

Scent is such an important part of food. It’s what catches our attention, enhances the flavor, and the memory of a smell stays with us long after the meal is over. Annabel’s Birthday Cake by Marissa Zappas captures that feeling perfectly with its sweet nostalgic notes of lemon sugar, tuberose, honeycomb, and roasted tonka. It makes you feel like a little kid at a birthday party again, swiping your finger through delicious fluffs of frosting when no one’s looking.

LOOK

Stephanie Temma Hier uses surreal, sculptural frames to turn her realistic oil paintings of food into delicious otherworldly platings. Her layering of materials, coupled vivid hues, reminds us that food can be a site of creative play. My favorite piece of hers, Sparks and Tremors (2021), pictured above, makes my mouth water.

In 1998, conceptual artist Sophie Calle embarked on The Chromatic Diet where she ate foods of a single color each day for almost a week. The project combined performance with photography as Calle documented and consumed her meals. The arrangement of these homogenous plates have an uncanny quality to them, appearing so unnaturally uniform and geometric that one would mistake them for artificial sculptures. Calle wrote descriptions for each dish in the style of a fine dining menu, noting little adjustments and details such as substituting yellow potatoes for white rice and milk and completing her fixed portion of tomatoes, steak tartare, and pomegranate seeds with roasted red peppers and a glass of red wine.

Mark Dion and Dana Sherwood’s installation Conservatory for Confectionary Curiosities (2008/2019) first caught my attention at the deCordova Sculpture Park in Lincoln, Massachusetts. Encased in a glass outer shell, the work’s interior is richly decorated with an array of brightly colored food-shaped forms. Yet the closer you look, the more you notice the pieces’ saccharine artificiality—and bugs trapped in the Jell-O-like molds. Dion and Sherwood are interested in the way humans construct nature through parks gardens, and how non-human actors become entangled in our culture.

One element of Janine Antoni’s 1992 sculptural installation Gnaw is a 600 pound cube of chocolate. Sitting on its gallery pedestal, the piece resembles a block of wood or marble. The weathering around its edges doesn’t come from carving tools, however. To create the work, Antoni used her mouth to bite away the corners, leaving behind a pattern of teeth marks. The piece is a reminder that our body is our most powerful tool.

LISTEN

America’s Test Kitchen’s podcast, Proof, is full of bite-sized episodes about food history and culture. I eagerly await each new season and all of the culinary tales and food misadventures they bring. Some absolute gems include cooking meals for your dog, the secret history of celery, the Indigenous science of corn nixtamalization, and Minute Maid and Tropicana’s battle for the orange juice market.

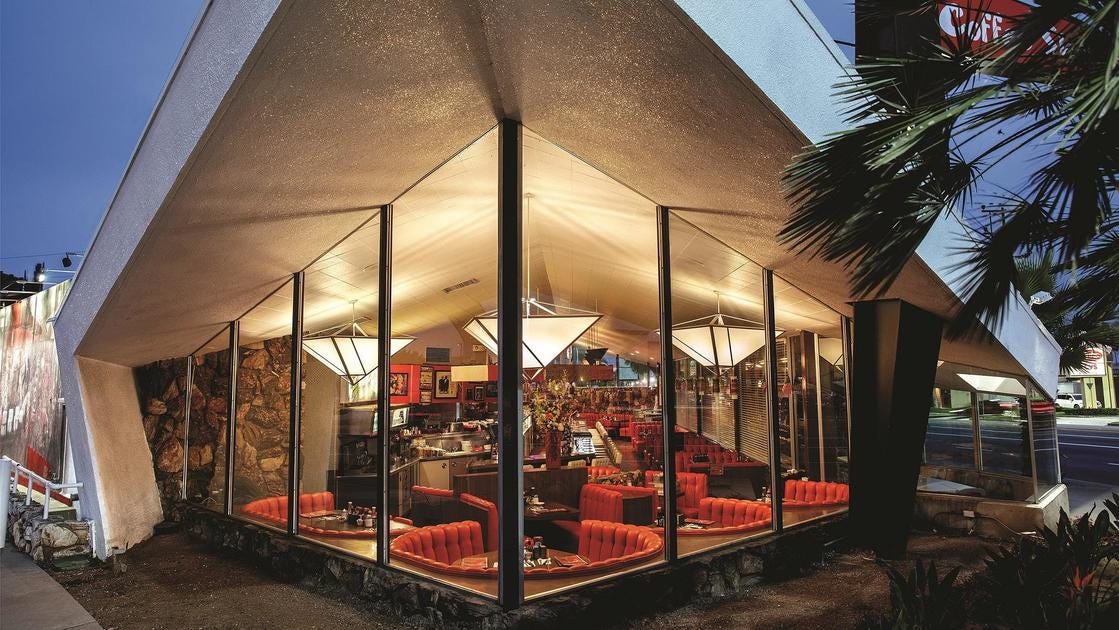

Googie architecture: a futuristic, Atomic-age atomic style with a silly name you probably associate with 1950s Southern California. But did you know about the female architect who brought Googie’s iconic geometric designs to Los Angeles’s diners and coffee shops? New Angle: Voice has a fantastic episode about Helen Liu Fong, one of the leading architects in the Googie movement, whose contributions to Californian design have been forgotten in American architectural history.

If you’ve ever seen a delicious (or absolutely disgusting) meal on the screen and wondered what went into creating that little piece of movie magic, I suggest you listen to this great interview with food stylist Janice Poon for Milk Street Radio. Poon, whose credits include the stomach-churning thriller Hannibal, shares her secrets for creating realistic meals (even in fantastical worlds) that actors can safely eat on-screen.

LICK

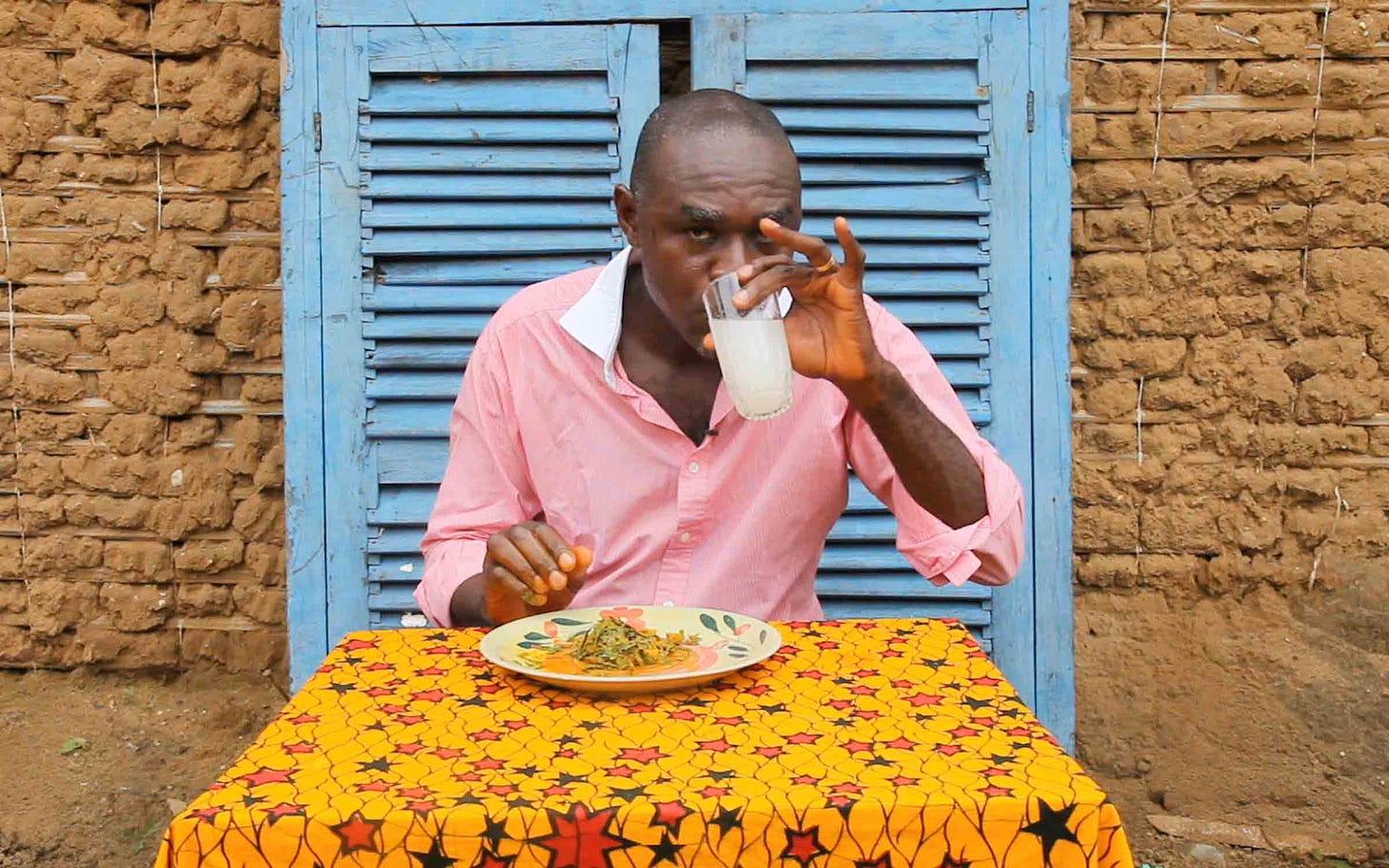

From 2014 to 2016 and in 2019, artist and filmmaker Zina Saro-Wiwa created Table Manners. All 16 videos in the series feature people from Ogoniland eating in front of the camera. Throughout the meal, her subjects stare directly at the viewer, engaging them as observer and dining partner. The project becomes like a power play between the eater and the audience, challenging the colonial gaze with self-determined acts of consumption enriched by local scenery and traditional Nigerian foodways.

If you’re ever in the mood to look at some weird old recipes with questionable ingredients, Cursed Cookbooks satisfies that craving. There’s lots of dishes with savory things suspended in gelatin, a concerning amount of ketchup and mayonnaise, the occasional animal made out of veggies, and confections made out of meat. It’s a funny look at the trendy foods (and unsettling combinations) of years past.

Like everyone else on the Internet, I’m now addicted to watching Amelia Dimoldenberg’s Chicken Shop Date. The format is simple: Amelia goes on a date with a celebrity across sports, entertainment, or music. Absurd questions, deadpan jokes, awkward silences, and (of course) fries and fried chicken ensue.

Unseen Edible is a project with a simple, yet fascinating, premise: what if we used to lichen to feed our collective future? First created by designer Julia Schwarz back in 2017, the project is a speculative fiction/documentary hybrid that imagines a time when lichen becomes a staple in our diets. Despite being very resilient and grown in abundance during famines, lichen is still viewed mostly as detritus. Yet, Schwarz’s experiments show how lichen could be used to address nutritional needs and food shortages brought on by climate change. Schwarz designed a whole toolkit for lichen harvesting, and even made a line of food products that incorporated lichen into bread, butter, pesto, and pesto that people could try IRL. Schwarz’s fascination with low impact, planet-friendly foods has grown into the collaborative design studio, Simiaen.

A long time ago, I worked as a gallery attendant for a pop-up show on the Upper East Side. One of the exhibited pieces was Alison Nguyen’s Dessert Disaster (2017-2018), and I think about it to this day. Comprised of found footage of disasters and over-the-top food commercials, the video work’s playful juxtaposition draws parallels between our hunger for disaster porn and our culture of overconsumption.

CLICK

Nomi Stone’s poem, “Thinking of My Wife as a Child by the Sea, While We Clean Mussels Together,” is a lesson in tenderness. Stone captures that moment when the knife gently pries open the mollusk shell to expose their soft, briny interiors for eating. Stone’s meticulous preparation of her family’s meal becomes flavored by reflections on love, family, and fleeting memory. “Isn’t it beautiful and terrible to exist inside / time:,” she writes, “to already be not there but here then here—”

If you want a more historical look at food and eating, I’d suggest this great essay about greed and gluttony by Irina Dumitrescu. Dumitrescu, who is a scholar of medieval literature, challenges the notion that gluttony is something that should be punished and invites us to reconsider a form of desire that has long been deemed a sin. It’s a thought-provoking piece about the relationships we build with food and each other.

The at-home bread baking craze isn’t going away anytime soon, but Seamus Blackley’s efforts to bake with yeast from Ancient Egypt takes this love to a new extreme. In 2019 Blackley—who, in addition to being one of the creators of Xbox, is an amateur baker and Egyptologist—partnered with a microbiologist to extract some samples from Egyptian ceramics. He then revived the dormant yeast, feeding it until he had enough to make a loaf of bread. The taste of these ancient grains? “Light and airy.”

Back in the 1960s, Pamela Strobel, also known as Princess Pamela, turned her apartment into the Little Kitchen, a soul food eatery that ended up hosting the likes of Gloria Steinem, Andy Warhol, Diana Ross, and Ringo Starr. Three decades later, she closed up shop and disappeared from the New York City food scene without a trace. Mayukh Sen traces Strobel’s life and legacy in this wonderful profile for Food52. As Sen digs through rumors about Strobel’s fate, her coming-of-age in restaurants, and tales of legendary meals paired with Pamela’s brand of fierce hospitality, he paints a vibrant portrait of a woman whose influence we can still taste today.

Aimee Nezhukumatathil’s poem, “Baked Goods,” perfectly captures the delicious chaos of assembling a recipe. Despite it being absolutely freezing right now, Aimee’s lyricism immediately transports me back to my stuffy apartment kitchen in July as something boils over on the stove, dirty dishes pile up in the sink, and stomachs growl in anticipation of a delicious homemade meal. Nezhukumatathil puts it best: “Our kitchen is a riot / of pots, wooden spoons, melted butter. / So be it.”