This past month, I kept breaking tableware. It would be with the bump of an elbow off the counter, a dish slipping out of my hand mid-scrub, the jolting sound of the shatter, the scramble to get the dust pan and broom, shards piled up into a safety hazard burial mound in the garbage can.

It’s been a month of disrupted patterns, the sowing of divisions in communities across our countries, broken promises. As bleak as it’s been to turn on the news, to witness that fracturing, I’ve been thinking about the power of fragmentation. What it means to dismantle, to take apart, unravel, obliterate. What it means to then reassemble those broken pieces back together, the impossibility of doing so, the pieces that are left behind, what we can find in the splintering cracks of that new whole.

TOUCH

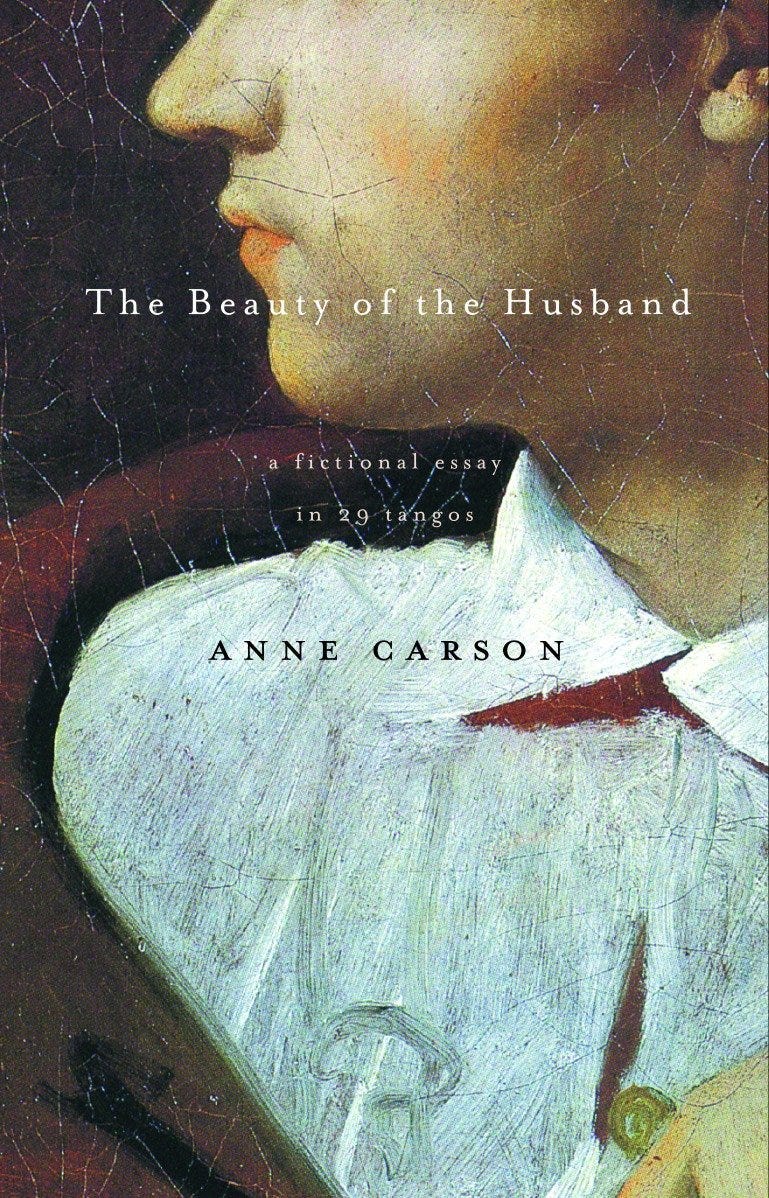

The slow turn to spring put me in the mood to reread Anne Carson’s The Beauty of the Husband. Broken up into 29 ‘tangos’ this poetic fictional essay hybrid is an elaborate choreography in heartbreak. Despite the book’s meticulous regimentation, the relationship at the center of this story is in a perpetual state of disorder, torn apart through repeated betrayals and re-entanglements, in a perpetual state of breaking. At one point, Carson muses, “A wound gives off its own light / surgeons say.”

Wangechi Mutu’s solo show Intertwined turns the galleries of the New Museum into a series of engagements with mythic symbolism deconstructed and reconstituted into hybrid Afrofuturistic forms. Mutu’s rich body of work—spanning bronze, collaged paintings and photographic images, animated video, and mixed media sculpture—embraces the intersections and striations of diasporic and African histories, legacies of colonization, and contends with present struggles in the face of globalized consumerism and the climate crisis. This show is a science fiction archeology site, where you can spend hours excavating Mutu’s profoundly layered imagery.

I read Kristina Lyons’s Vital Decomposition: Soil Practitioners and Life Politics for a class I’m in about decay. Lyons shares the story of soil practitioners ranging from state scientists to campesinos and Indigenous farmers, tracking how they became separated from the land through Colombia's armed conflicts (which led to outlawed plants, toxic fumigation, and remnants of explosives embedded in the landscape) and resource exploitation. This ethnography weaves itself into the divisions among humans and the Amazon's vibrant ecology, revealing decomposition's ability to connect species, regenerate knowledge, and grow agricultural resistance.

LOOK

I would be remiss if I didn’t discuss the work of Cornelia Parker. Most known for her rooftop commission at the Met, Parker’s practice is shaped by her deconstruction of domestic objects to form uncanny new assemblages. Parker has described her actions as “cartoon violence,” testing the limits of materials in her installations. I love her 1991 piece, “Cold Dark Matter: An Exploded View,” where she blew up a literal shed then reassembled the exploded fragments into a state of suspended animation, freezing this moment of destruction forever. Parker was fascinated by the archetypes of the shed and explosion, two images associated with childhood colliding together.

In 2007, Doris Salcedo fractured the Tate Modern’s great Turbine Hall with a giant crack all the way across the floor. Titled Shibboleth, this intervention marked a number of social, political, and cultural fractures she witnessed at the time. For Salcedo, Shibboleth signaled ruptures in literal space and time, yet it also marked divisions of racial hatred, economic violence between the Global North and South, militarized borders, and exclusionary histories of museums where artists of color continue to be marginalized. The crack was sealed at the show’s end, yet its scar is still visible today.

I’ve been following Naoko Ito’s Urban Nature projects for quite some time now. Ito has this magical ability to bottle up trees—literally—through her mind-bending sculptures. I’ve always wondered how Ito gets the branches precisely arranged in jars, how methodical the act of cutting up the tree becomes in order to fit into this precise geometry. Ito’s pieces troubles the division between nature and artificial construction.

LISTEN

Last year, NPR’s Throughline published an episode about the history of the Partition, the moment when India and Pakistan were divided into two countries. The impact of this division was tremendous as 15 million people were displaced in one of the largest mass migrations in modern history that still impacts families and communities today. I appreciated how this episode balanced discussions of historical records and national politics with peoples’ memories from that time of chaotic, polarizing violence.

Sobolik’s Packet Loss is a four-track journey into glitchy, refracted rhythms. “Fk Around and Find Out” has an infectious bounce, luring you into groove with delicious textures. “Update” kicks things off with a playful frenzy while “Cope” marks a deeper unraveling, embracing synth-y contradictions and percussive ruptures in the soundscape. “Airplane Mode” marks an ecstatic peak in this adventure, an adrenaline rush of a song of explosive momentum and reached breaking points. The album has a seamless, science-fictional flow to it, sizzling with a beautifully electric disorder.

LICK

I'm not exaggerating when I say that Severance is one of the best pieces of television I've ever seen. Set in a near-future world where a biotech corporation invented a procedure that allows workers to split their consciousness in two, the show is a biting critique of corporate labor and the dehumanization of our hyper-capitalist office culture. I won't say too much more about the plot (this is the type of show you should go into totally blind), but I will say that this is a perfect cast with phenomenal performances and Ben Stiller's incisive directorial eye imbues this thriller with a wickedly dark sense of humor and a blandly dystopian corporate aesthetic.

Despite the passage of NAGPRA, which was meant to offer legal guidelines for returning Indigenous remains back to impacted tribes and nations, repatriation efforts in the United States remain woefully inconsistent and at miniscule numbers. In a time when museums keep their collections in accessible, a federal database of NAGPRA-eligible artifacts is nowhere to be found, and an unfair burden is placed on tribes to prove their claims, I found ProPublica’s database about the number of Native American remains in museum collections to be a refreshing step forward to greater institutional transparency and accountability. The forced removal and looting of these individuals’ graves marked a traumatic rupture from their communities, and this project has the potential to reunite tribes with their stolen ancestors.

A friend of mine recently got a Piecework puzzle for their birthday. I haven’t done puzzles since I was a little kid (the go-to activity when we'd lose power during hurricane season), so I loved being able to jump into a design that feels fun, fresh, and fits my grown-up taste. I especially love how each puzzle comes with its own custom playlist to set the mood. Each one is the perfect soundtrack for a few playful hours spent with friends (or a glass of wine, or both) putting pieces back together.

CLICK

Author’s Note: I’ll be honest, I didn’t have the attention span to read any longform writing this month. It feels fitting to include only poetry in this section, a literary form that values line breaks and fragmented language above all else.

In “Dream Particles” by Layla Azmi Goushey reckons with the explosive legacy of the Fourth of July. Goushey grapples with her son’s excitement, how their beams of light resemble drones, and she begins to contemplate the lives of other families who, rather than celebrating, find themselves victims of rocket strikes. Goushey describes how “the fireworks’ ashes rain down into our sweet, iced tea.” The façade of joyous patriotism begins to crack, a reckoning erupts from these fissures. As she puts it: “we consume the bitter dream particles and digest them into a lesser form.”

“Burn” by Janice N. Harrington begins with a “prairie cut,” wind and wings carving into the landscape. Harrington dissects this site like a surgeon with an open wound, extracting visual details of this unique ecology and the many flora and fauna that call it home. In some ways, this is a poem about looking, but observing with eyes alone is not enough. As a piece of her hair gets ripped from her head by a breeze, and weeds are uprooted by local naturalists, Harrington muses on her hair’s eventual decay and consumption by the earth. “In a prairie, I am chance,” she writes, “I am rupture.”

Mark Strand’s “Keeping Things Whole” beautifully articulates what it’s like to feel empty, separate, and distant, finding oneself only in absence even as you try to reconnect with the world around you. Strand’s clipped line breaks add to that feeling of self-fragmentation. I love this stanza in particular: “When I walk / I part the air / and always / the air moves in / to fill the spaces / where my body's been.”

I first learned about Janine Joseph’s poetry through an interview she did for Poetry Off The Shelf, where she recounted her experience recovering from a car accident that left her with a traumatic brain injury, and how that impacted her writing. As I dove more into her body of work, I came across “Circuitry,” a poem that pieces together fragments of the accident and its aftermath Each line break is a suspended breath, pausing in between to recount the series of events. In this embrace of glitched remembering, Joseph asks, “ Can you point for me where / it happens in the connection, where / on the line the old equipment / resets itself and loops?”