58. Architectural Reliquary (I)

For this month’s newsletter, acts of building up and tearing down.

Despite having no desire to draw or build things myself, architecture has almost always been on my mind. One of the first books of art criticism I ever read in high school was not really art criticism at all, but rather critic Paul Goldberger’s (now out-of-print) Building Up And Tearing Down Reflections on the Age of Architecture. Since then, I’ve taken classes on architectural history, wrote about architectural influences in animated film, worked for the Center for Architecture here in New York, and am now focusing on climate resilient museum architecture for one of my master’s theses.

Once you start noticing you can’t stop—little details like the sloping of walls, the placement of windows, where light falls across an interior, how layouts guide the flow of movement, how materials contrast with or play off of local color and textural palettes, socioeconomic, and ecological histories. Architectural practice, theories, and techniques are constructions, shaped just as much by us as we are emotionally, mentally, and creatively influenced by them. I want to use this opportunity to pull back the curtain on the façade, to focus on the process not just the final product, to show how the built environment can reinforce social norms or challenge political convention, to unsettle the field’s fixed notions of permanence and perfection. So for this month’s newsletter, acts of building up and tearing down.

TOUCH

How did architects respond to the rise of environmentalism in the 1960s and 70s? While discussions about green architecture and sustainable, low-carbon building are now part of mainstream debates, MoMA’s show Emerging Ecologies charts the lesser-known of the philosophies and political movements that brought forth new innovations in environmental design. Many of the projects featured in the exhibition were never built yet were influential nonetheless in their radical calls for rethinking our relationship to nature. Beyond displaying models and sketches, the show explores how the rise of environmental justice movement and second wave feminism, as well as critiques of consumerism and pollution, raised important questions about designing for more equitable futures on the land, the ocean, in outer space, and underground.

Out in Architecture is a wonderful compendium of essays and interviews by architects from across the LGBTQIA+ community. Where other discussions about diversity and inclusion in design tend to focus on corporate principles of DEI and impersonal statistics, I appreciate that this book centers these architects’ lived experiences, making space for them to express in their own words how they’ve navigated the workplace as out (or not), and how their design perspectives and approaches to projects have been shaped by additional intersections of identity like race, gender, class, and disability. As the architecture field continues to experience its own professional reckoning, this is necessary reading.

Last month, I had the chance to attend a talk at the Cooper Hewitt by landscape architect Kongjian Yu. Yu has earned international acclaim for his concept of the “Sponge City,” an innovative approach to urban design that seeks to revitalize, remediate, and make resilient areas in cities that are prone to flooding. Yu walked us through his philosophy, noting how his upbringing in the countryside taught him important lessons about staying connected to the land and finding strength in dynamic fluidity. Yu’s ecological infrastructure projects embrace the growth of greenery and have found proven success by letting natural movements of water ‘breathe’ by dismantling traditional non-porous concrete flood walls. It was impressive to hear Yu discuss the process of his projects from start to finish, and how they continue to reduce flood destruction in the years after their completion. Cheaper, faster, and self-sustaining, Yu’s practice offers a promising look into the future.

For one of my final projects this semester, I’m working on a research paper about the role of olfaction in the sensory experience of nightlife, a topic that’s sent me into a rabbit hole of nightclub spatial design and rave infrastructures. John Leo Gillen’s Temporary Pleasure: Nightclub Architecture, Design and Culture from the 1960s to Today has been an invaluable resource with its historic look at the club scenes of New York, London, Berlin, Detroit, Chicago, and Ibiza. Gillen not only focuses on iconic venues and exclusive clubs, but also celebrates the designs of DIY venues as vibrant ephemeral spaces to dance, find community, and experience disorienting release.

LOOK

Curry Hackett is a designer who is using AI to envision alternative Black architectural futures. He has imagined churches made from red clay and Appalachian quilt patterns, Chicago two-flats made with quilted brickwork, playgrounds inspired by Black hair, and (my personal favorite) Florida homes with inflatable porches. I’d recommend pairing a scroll through his feed with his interview with Bloomberg and an essay he co-authored for e-flux about racial epistemologies in the architectural canon.

I’ve been fascinated by Rachel Whiteread’s practice for some time now, how she’s able to turn cast forms of building fragments into ghostly sites heavy with the weight of memory, time, loss, and displacement. Where architecture is meant to welcome you into a space, Whiteread denies the viewers access through the solidity of her pieces. While I’ve had the chance to see Whiteread’s monumental works in galleries and museums, I still think about her 1993 public artwork House. The form was cast from a Victorian terraced house in East London that was slated for demolition. When the sculpture was placed in the location where the house once stood, its surrounding homes had been completely flattened, leaving the sculpture all alone in a new public park. Eventually Home was also demolished, but not before it sparked intense public debate about the emotional ties to home, housing rights, and economic precarity.

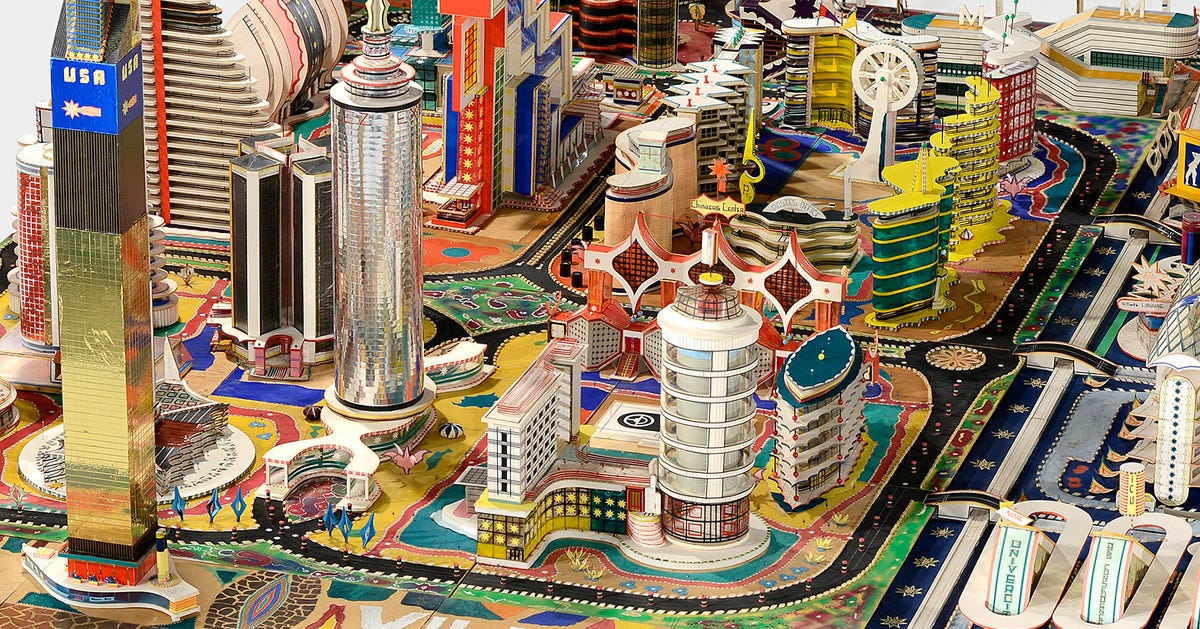

Model-making is a vital part of the architectural process, enabling designers to translate ideas from the page or the computer into a small-scale, 3D construction of the site to study and present. Bodys Isek Kingelez uses the architectural model as his sculptural medium to imagine vibrant worlds from entire cities to standalone buildings. At first glance, you’re struck by each piece’s colorful beauty. But the more you look, the more you notice how these sculptures are textured with found everyday objects like soda cans, packaging, foil, and plastic. Born after the Democratic Republic of Congo’s independence from Belgium, Kingelez sought to create utopian urban futures, where architecture can flourish alongside societal growth, heal past wounds, and embody optimistic dreams of the future. I saw Kingelez at MoMA in 2019 and I’ll never forget how visitors spent hours studying his meticulous worlds.

I’ll never forget the first time I saw photographs of a building by Lina Bo Bardi. I was stunned by the raw geometry and sharp linearity of her structures, contrasted by these electric bursts of color that became symbolic of Brazilian Modernism. Bardi didn’t design passive spaces, she wanted to design monumental habitats, where people (especially craftsmen and laborers) and their diversities of artistic, political, and cultural expression could thrive. The building that struck me all those years ago? SESC Pompéia in São Paulo which was adapted for reuse from an old drum factory that now houses sports facilities, workshops, restaurants, galleries, and theaters.

LISTEN

As Hollywood became the epicenter of filmmaking in America, the many performers, studio staff, and industry who came to Los Angeles to find fame needed homes that reflected new southern California sensibilities. Paul Revere Williams was the architect who brought their building ambitions to life all across the city. 99% Invisible published an amazing episode about Williams and his legacy back in 2017, and it remains one of the best architectural retrospectives I’ve heard. Williams designed buildings for big names like Frank Sinatra and Lucille Ball, constructed schools and hospitals, and contributed his expertise to the Beverly Hills Hotel, Howard University, and LAX. Despite being credited as a creator of the “Hollywood Style,” Williams never went to architecture school, only studying art and engineering before building up his portfolio. As a Black architect, he faced hostility from his colleagues and was often not welcome in commercial spaces he designed, yet his legacy still stands today.

If you love listening to people talk about their practice, how they’ve built their craft, and how they’re using design to build new futures and reflect on past histories, the Architecture Foundation’s podcast, Scaffold, is for you. Each episode features an in-depth conversation with architects, researchers, critics, historians, and visual artists who all approach the construction of spaces through their unique perspectives. Along with interviews with Tacita Dean, Sumayya Vally, and Moshe Safdie, their spin-off series Power & Public Space uses experimental projects to grapple with political issues.

What if we curated the music inside spaces the way we do home decor? While we experience that today in lots of commercial spaces and, thanks to home audio tech, we like to put on certain songs to match a space’s vibe, Kankyō Ongaku: Japanese Ambient, Environmental & New Age Music 1980–1990 compiles the songs of the artists at the forefront of the spatially serene genre of “interior music.” With proto-ambient melodies designed to reshape the feeling of a room and its furnishings, these soundscapes act like, as critic Simon Reynolds put it, “an environmental tint, closer to good lighting or incense than music as commonly understood: a nonintrusive complement that surrounds and enhances everyday activity.”

LICK

When I went to the Brooklyn Museum earlier this month, I got to see an exhibition dedicated to María Magdalena Campos-Pons, a multimedia artist known for her photography, installation, and performance works. I wandered into one of the galleries and was immediately met with a dress modeled after the Guggenheim Museum's iconic circular forms. This piece was made by Campos-Pons for a performance at the museum. Titled Habla Lamadre, Campos-Pons led a musical procession along its Frank Lloyd Wright-designed spiral, filling the Guggenheim's atrium with reverberations of singing and music. Campos-Pons led the way with a bouquet of roses and a vase, evoking the Yoruba deity Yemaya as she asserted the power of Black artists within the white-dominated institution. You can watch the moving performance online and see this architectural dress in action.

Failed Architecture continues to be one of my favorite outlets for architectural criticism. As the name suggests, the publication breaks away from traditional design media, elevating in-depth critical research projects over the industry standard of glossy editorial spreads and effusive articles that act as regurgitated press releases. Failed Architecture’s contributors take on the built environment in its many material, social, economic, and political forms, grappling with the way architecture foster connections and divisions within the spaces we move through. With a wide array of articles and podcast episodes to choose from, there’s something for everyone.

With the violence happening in Gaza and the West Bank right now, it’s been great to see architects and design researchers share their expertise about how systems of apartheid have been constructed in the region and continue to be used to enforce the restriction of movement, blockades of resources, violent military policing, and mass displacement through the encroachment of illegal settlements. I visited Israel and the West Bank back in 2016 and I still remember noticing the red roofs of settlements, the high barbed-wire walls, and complicated checkpoint systems, even if I didn’t fully understand their significance at the time. One resource I have found particularly helpful was a teach-in about the architecture of settler colonialism led by The Funambulist’s editor-in-chief Leopold Lambert. I’d suggest pairing Lambert’s lecture with a look through Forensic Architecture’s many geospatial and media investigations into incidents of violence in the Occupied Palestinian Territories to see how the land itself has become inscribed with the residues of systemic injustice.

CLICK

PIN-UP is one of my go-to reads for architecture and design, so I was delighted to read architect Oana Stănescu’s interview in the magazine with architect and professor Pierre de Looz. I really appreciated how the conversation moved between Stănescu’s approach to teaching design students, the life influences that have shaped her practice, and the role of play and public engagement in her projects (which range from collaborations with Virgil Abloh and Kanye West to a proposal to put a pool in the East River and an elevated park that revives the industrial history of her hometown. She wonders, “Can you create a place that just allows you to forget about that, to let your guard down, to communicate once more, see the world, see yourself, see everything through something way more visceral, more honest maybe?”

Earlier this month, I took a research trip down to Miami to photograph a museum down there. After I ended up spending the rest of the day in Miami Beach on the other side of Biscayne Bay, walking among the pastel hues and sleek modernist structures of its Art Deco District. I was reminded of a piece by Jessie Kindig I read back in 2019 about the history of Miami Beach and the Miami Design Preservation League is fighting to preserve its unique architectural history in the age of intensified storms and sea-level rise. Kindig raises important questions about what calls for climate resiliency actually look like, and what to do with the aesthetic histories we’ve inherited when their structures might not make it into the future. “Whom and what we love, whom and what we save, and how we mourn the things,” she writes, “we’re certain to lose are now becoming urgent questions of preservation.”

Back in June 2022, e-flux published a collection of essays under the theme of ‘Sick Architecture.’ As the editors note in their introduction, “Sick Architecture is not simply the architecture of medical emergency. On the contrary, it is the architecture of normality—the way that past health crises are inscribed into the everyday, with each architecture not just carrying the traces of prior diseases but having been completely shaped by them.” Each piece is a rich deep dive into histories of medical design, disability justice, wellness, toxicity, and show how social and biological ills shape bodies and buildings. A few recommendations: the role of whiteness in clean aesthetics, biopower in Ellis Island’s medical screening rooms, viral infrastructures, inclusive care home design, disabling building form, and autistic spatiality.

Neon Yang’s short story “Old Domes” follows a “cullmaster of buildings” as she attempts to ‘execute’ the spirit of Singapore’s Supreme Court building to make way for a new architectural marvel. I got absolutely sucked into Yang’s architectural world-building, where old building guardians are executed to make way for new ones and construction deities protect worksites. I love how Yang uses the buildings themselves, and the histories and memories they carry, to wrestle with Singapore’s practices of perpetual new construction, preservation, and renovation. This description beautifully sums up these elaborate entanglements of space and time: “A living corpus carved and recarved, hollowed by tunnels and multibasement carparks, its borders fed with the leftover rock and silicate. It was a young land, supple and stretchy, where maps a year old were outdated, their lines dancing a seismographic tango.”

Very happy to see Kankyo Ongaku in this piece. Great work.

So interesting!