62. Embroidered Reliquary (I)

As I write this, I find myself getting distracted by a loose thread on the shirt I'm wearing.

Hello friends,

As I write this, I find myself getting distracted by a loose thread on the shirt I'm wearing. It's right at the shoulder seam, perpetually upright and always in my peripheral vision. I could grab a pair of scissors and snip it (restoring a sense of order to my fashionable presentation) but it doesn't feel right to execute this string whose only crime was getting snagged by its human wearer at some point in its life as a garment. It'll stay for now, a reminder of this shirt's compositional vulnerability. A small hole accompanies it. Maybe one day I'll muster up the courage to mend it and leave my own trace of thread for another owner to notice when they wear it.

For as long as I can remember, I've always been fascinated by sewing. I grew up with my mother and grandmother spending nights in front of the TV hunched over worn socks, ripped blouses, and things in need of hemming or lengthening. I still remember trying not to get pricked with pins to adjust a dress for a school dance, and now I regularly bring my mending to the tailor. I've always been fascinated by garment construction's simple beauty, of fabric and needle and thread coming together to turn the geometric language of cut patterns into beautiful wearables that stitch together times, places, and cultures. For this newsletter, I'm thinking about the labor of sewing, stories told through embroidery, how we become stitched together, and how the tug of a single loose thread can lead to our collective unspooling.

TOUCH

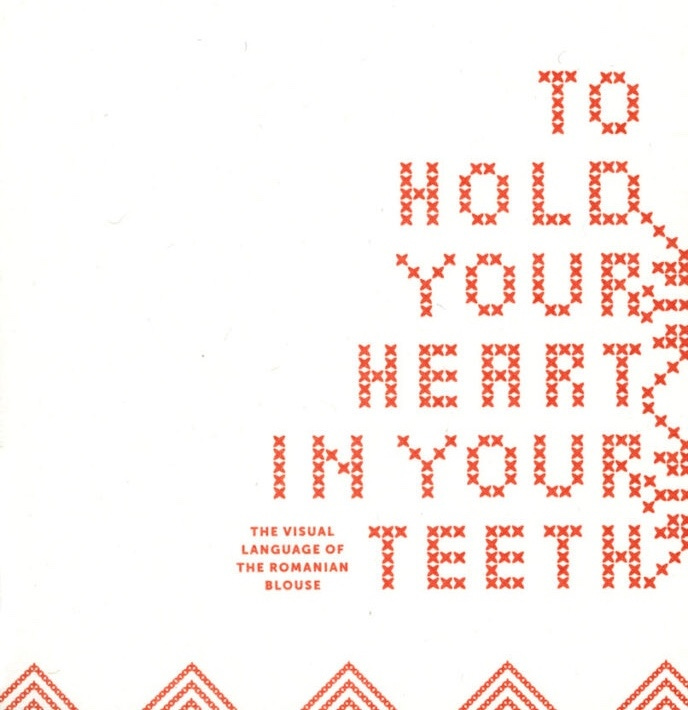

Simona Bortis-Schultz's book To Hold Your Heart in Your Teeth unravels the stories and symbols found in traditional Romanian blouses. This book made me so emotional, seeing not only parallels to my own family's experience but also giving visual language to embroidery motifs I grew up seeing (and wearing). Bortis-Schultz takes us into rooms where blouses are hand woven from hemp, grapples with her own history of immigration, and explores how these folk traditions shifted in the communist and post-communist eras. More than anything, Bortis-Schultz's study is a testament to generations of feminine resilience preserved through craft.

At the end of last year, I picked up a tank top from the Ramallah-based brand Nöl Collective. I first became aware of their work with Palestinian artisans through a video they made about their experience travelling between craft communities while also navigating the Israeli apartheid regime's system of checkpoints and roadways closed off to Palestinians. Nöl Collective embodies sustainability in a way that other fashion brands rarely do, not only by using handmade woven fabrics and deadstock but also directly supporting makers and their families across Gaza, Bethlehem, Ramallah, and Jenin. This particular piece is embroidered with tatreez, a tradition of cross-stitching done by embroiderers in Naqoura Village just outside of Nablus. Even with brutal military crackdowns, the Collective continues to make and send out their pieces all around the world, and I can't recommend supporting them enough.

Common Threads Press is a small publisher based out of the U.K. specializing in zines and books about radical and overlooked histories of craft. They first got on my radar with Stitching Freedom: Embroidery & Incarceration by Royal School of Needlework curator Isabella Rosner and have quickly become one of my favorite indie presses. While Stitching Freedom explores needlework made by women and men produced within the confines of prisons and mental health institutions (from suffragettes and those struggling with addiction to concentration camp victims and survivors of slavery), other titles like Many Hands Make a Quilt: Short Stories of Radical Quilting and, more recently, Mauka to Makai: Hawaiian Quilts and the Ecology of the Islands invite us to learn about collective and individual experiences of finding community and preserving histories and cultures through sewing and making.

LOOK

Last week, I got to see Pacita Abad's first retrospective at MoMA PS1. Spanning over 30 years of a vibrant career in quilting, painting, and paper sculpture, I was awestruck when I walked into the gallery and was met with walls filled with monumental textile paintings. Abad was known best for her trapuntos, where she stuffed and stitched colorful cloth onto painted canvases to give them a multi-dimensional quality. With each tug of the needle, Abad (herself a refugee who fled the Philippines in 1970) embedded political messages in her work, drawing our attention to marginalized peoples, multicultural identity, and immigration through her expressive textiles.

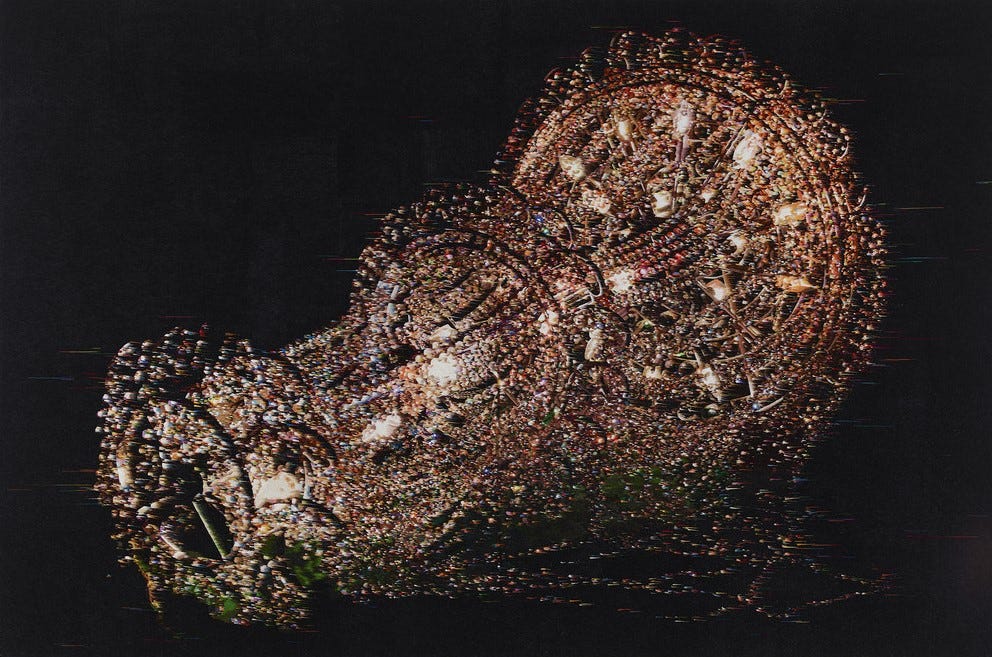

The first time I saw one of Kyungah Ham’s pieces, I thought I was looking at a blurred photograph of a chandelier. Yet, on closer inspection, it becomes apparent that these images are constructed through needle and silk thread. Beyond the immediate ephemeral beauty of these pieces, Ham’s work seeks to bridge divisions between North and South Korea through the shared cultural thread of embroidery. Ham constructs each needle painting by smuggling each pixelated digital design to North Korean artisans who then send it back to the South through intermediaries once they finish the stitching. Ham is interested in communication and reunification, and taps into embroidery’s history as a visually coded language to achieve this. The endeavor is not without risks. The embroidered works are often confiscated or damaged in transit.

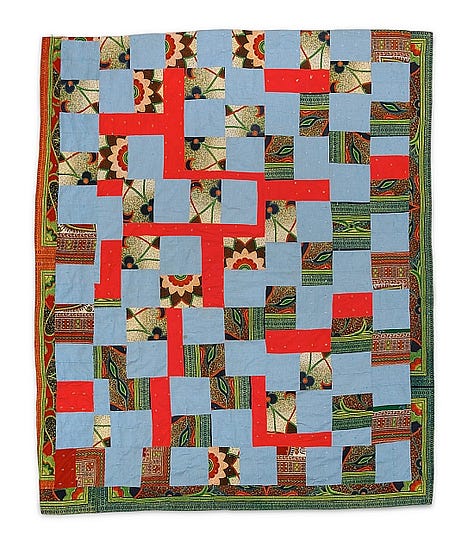

Lately, I've been thinking about the quilters of Gee's Bend. Since the 19th century, generations of this Black craft community in Alabama have fought to preserve their textile making traditions through the end of slavery, sharecropping, during the Great Depression, and as acts of creative collective liberation during the Civil Rights Movement. There's nothing like these quilts, emblems of not only Southern American folk traditions, but also lively and vibrant experiments with geometric abstraction. In recent years, Gee's Bend has garnered national attention, with their quilts appearing in museum exhibitions and collections. Today, you can still go visit their workshops (I hope to do so one day). If you can't make it down to rural Alabama, you can support these quilting families directly on platforms like Instagram and Etsy.

After returning back from military service in 1945, Jacob Lawrence began a series of paintings that featured Black workers. The Seamstress (1946) is one of my favorites. Lawrence’s dynamic Expressionist style brings the fabric workshop to life, presenting sewing as an art form requiring great technical skill and dedication to the craft. As the American post-war period saw the acceleration of mass consumerism, Lawrence draws our attention instead to the overlooked Black laborers he encountered in small workshops around Harlem and their vital roles as makers for the community.

LISTEN

Avery Trufelman’s Articles of Interest explores the history behind the items we wear everyday and how shifts in our culture, politics, and the economy have transformed how we design clothes and how we get dressed. You may have heard of the show because of its multi-part “American Ivy” series that explored the history of preppy style. But there are so many other great episodes to choose from like one on pointe shoes (balletcore anyone?), prison uniforms (done with Ear Hustle), Cher’s iconic closet from Clueless (1995) and the complicated history of the Hawaiian shirt (perfect for summer). Trufelman takes us beyond what’s trendy to look at the innovative materials, garment construction, labor histories, and social justice issues that feed into fashion.

Back in April, we lost artist Faith Ringgold, a monumental force known for her creative practice that mixed media like painting, sculpture, and performance with a deep commitment to activism. Last year, when Ringgold had a retrospective at the New Museum, an entire gallery was dedicated to her bold and beautiful “story quilts.” Notes From America did a great episode about Ringgold’s legacy, speaking with her daughter about the stories of creative power depicted on these textiles.

Hosted by Recho Omondi, The Cutting Room Floor features conversations with people working all across the fashion industry, from designers and models to brand strategists and stylists. These interviews are wide-ranging and deeply incisive as Omondi’s guests reflect on their own relationships to style, how they’ve built their companies, and how they envision the future of fashion in this time of social media, celebrity culture, and hyper-overconsumption. Omondi is such a skillful interviewer, and it’s so refreshing to see her subjects speak frankly and comfortably about the good, bad, and the ugly of their experiences. The show switched to a video format in 2023 but you can listen to older (yet still relevant) episodes here.

LICK

If I could pick a single fashion newsletter to subscribe to, it would have to be my friend Em Seely-Katz's

. I'm obsessed with the way they think about fashion, writing about how clothes can become a way of experimenting with your gender expression and reflective of the pop culture you consume. Their ability to track down such unique, beautifully-constructed pieces and draw unexpected connections between current trends and fashion history is truly unparalleled. Whether you're on the hunt for some new things or hoping to learn about talented emerging designers, their recommendations and predictions will be exactly what you're looking for. Not sure where to start reading? I love their "My Style Heroes" series, dressing like a One Piece character, CAPTCHA clothing, and their wearable poetry looks made my literary heart sing. I’m always so excited to see them in my inbox.

I had no intention of talking about Paris's Haute Couture Week, but I was absolutely blown away by the artistic embroidery of Thom Browne. "Haute couture" as a concept represents a deep commitment to the artistry of tailoring and dressmaking, and now reflects a strict series of production standards for fashion houses to follow (such as having a Paris atelier, made-to-order designs, and at least 20 technically skilled employees to make garments for each seasons). Thom Browne's Fall/Winter 2024 collection embodied this passion for fashion as a craft, with models walking down the runway in elegant white monochrome sets accented with meticulous stitching and playfully precise tailoring. A whimsical dream, as always.

If you’re a Game of Thrones fan like me, then you probably noticed a new opening credits sequence for the latest season of House of the Dragon. As a huge lover of medieval art history, this made my heart sing. The showrunners wanted the design to emulate the famous Bayeux Tapestry (a handmade depiction of the 11th century Norman Conquest of England) and worked with the studio yU+co to weave an elaborate narrative of the Targaryens’s rich and bloody family history. Given that House of the Dragon grapples with issues of gender, it feels apt to model the design after an artwork embroidered by women whose labor and histories have only recently garnered the attention they’ve deserved (and spurred modern attempts at recreation).

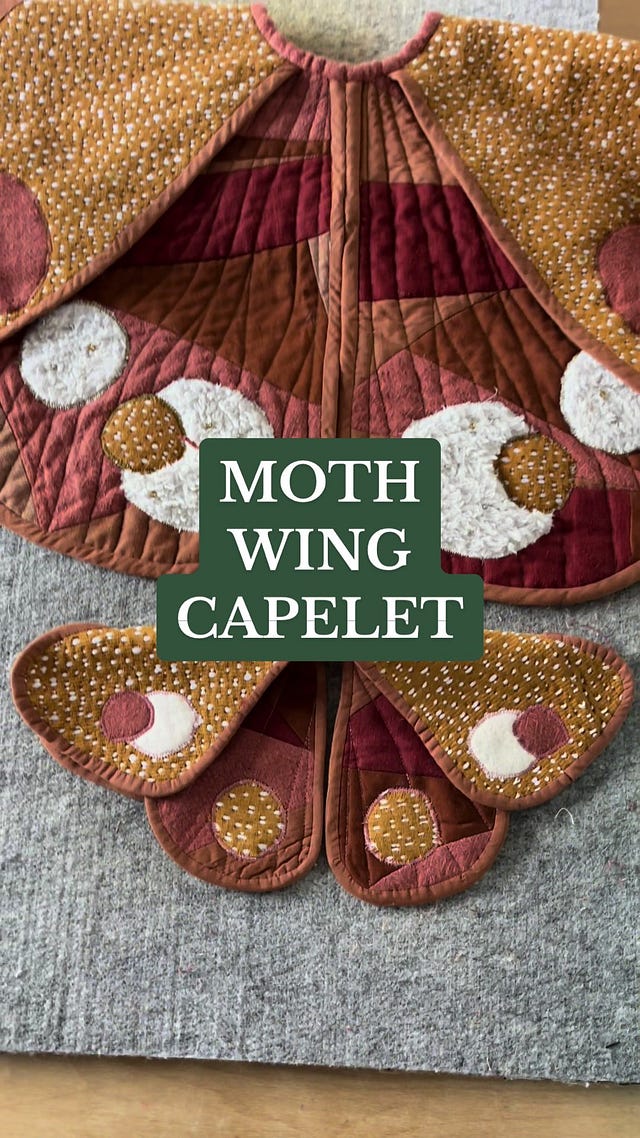

It would be silly of me to make an entire newsletter about embroidery and not include at least one tutorial or resource for my readers who might like to embark on a DIY project of their own. I want to the wonderful creative work of Rachael Gilbert-Burns (aka MinimalistMachinist). I first got connected with Rachel over TikTok and I continue to be obsessed with her passion for mending, quilting, and making. Her practice can feel downright futuristic at times with the way she experiments with technologies and processes. I highly suggest exploring her tools and patterns.

CLICK

I would be remiss if I didn’t include a critical look at the impact of our textile and clothing consumption on the environment. I still think about this story from Wired by Matt Simon about scientists discovering microfibers and plastics in the isolated waters of the Arctic Ocean. In the water samples they collected, nearly three-quarters of the fibers they found were synthetic polyester, undoubtedly entering these ocean currents through dumping and drainage from washing machines. As these fibers become part of our ocean sediments (and textile waste remains a pervasive problem on land as well), it’s clear that these destructive behaviors have and will continue take a toll on the health of these ecosystems as marine life continues to consume them.

From 2014 to 2018 at the University of Applied Arts in Vienna, a team of artists and makers embarked on a research project called Stitching Worlds. Their goal was to explore textile technologies and digital fabrication asking, among many questions, “What if electronics emerged from knitting, weaving and embroidery? How would technology be different if craftspeople were the catalyst to the electronics industry, via textiles manufacturing?” Their website is a fascinating archive of their findings, categorizing insights into speculation, study, experimentation, and reflection & dissemination. Over its lifespan, Stitching Worlds became an exhibition where these experimental projects were displayed. Now, the project lives on in the open-access book Stitching Worlds: Exploring Textiles and Electronics.

In a time when reading fashion magazines can feel boring and uninspired (the same brands with lame listicles that are always on the risk of shuttering), I always get a kick out of SSENSE’s editorial content. It’s all over the place in a way that I appreciate. There are conversations with creatives like emerging designers, stylists, models, and photographers, the occasional book or film recommendation, and deep-dives on fashion in pop culture. Some recent favorites have been their look at the style of the infamous TV network Bravo, screen-friendly clothing, and their Color Story series.

I always like to end these newsletters with a work of poetry or fiction. It feels fitting—after our discussions of how practices of sewing and embroidery intersect with issues of gender, power, and labor—to conclude with Carmen Maria Machado’s short story, “The Husband Stitch.” The story unravels like a fairy tale, beginning with a ribbon tied around a girl’s neck and ending with a haunted fraying of body and mind.