63. Woven Reliquary

Entwined between hands and machines, these wondrous arts of making have crossed tremendous distances of space and time through the simple twist, tuck, and knot of a single piece string.

Hello friends,

In one of her iconic journal entries, science fiction writer Octavia Butler declared herself a “WORDWEAVER / WORLDMAKER.” I’ve always been envious of people who can knit and crochet. There’s something utterly marvelous about watching the choreographed movement of hooks and needles, the rhythmic swing of arms pulling yarn across a flat knitting machine, a spool’s careful unraveling. These crafts have their own poetic language, manifested in the geometric designs of punch cards or the abbreviated sets of letters and numbers found on patterns. Weaving is another world of its own with looms that take up a whole room, be the size of your palm for darning, or anchored to the body, raising its warp and weft from floor to ceiling with varying degrees of manual labor and automation.

Within these choreographies of making, stories are spun, songs are plucked from threads, knowledge is shared, community is made. We become bound not only to each other, but to legacies of craft that go back generations. Entwined between hands and machines, these wondrous arts of making have crossed tremendous distances of space and time through the simple twist, tuck, and knot of a single piece string.

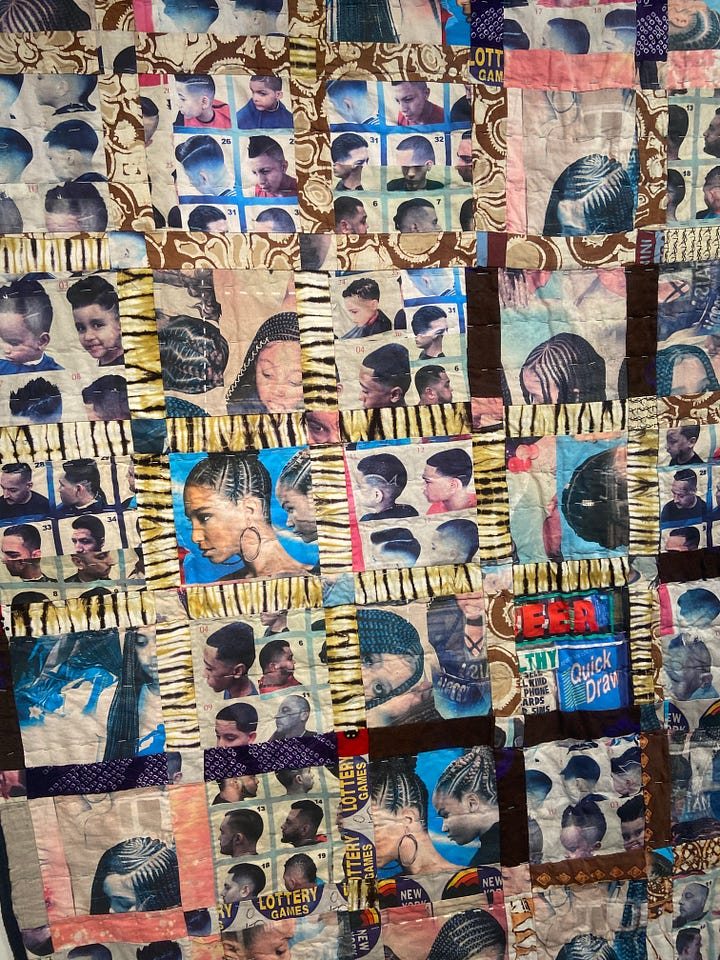

TOUCH

Earlier this month, I got the chance to experience the work of textile artist Cassandra Mayela Allen. Her show at Olympia, Desahogando: Undrowning, features an array of weavings and quilts that map out the experiences of New York City’s migrant communities amidst socioeconomic precarity and threats of further displacement under gentrification. I was struck in particular by Color Studies I (2022) and June (2024), each created from up-cycled clothing donated to Mayela Allen by fellow Venezuelan migrants. The closer you look, the more you find recognizable symbols of the weaving’s past material lives: a tag from a pair of Levi’s jeans, shiny strips of corduroy, and polyester patterns. Along with her hand-sewn quilts (which feature images of bodegas, barber shops, and hair braiding salons), Mayela Allen invites us to reflect on how we consume resources and find community, showing us how these textiles help preserve immigrant histories through acts of making and mending.

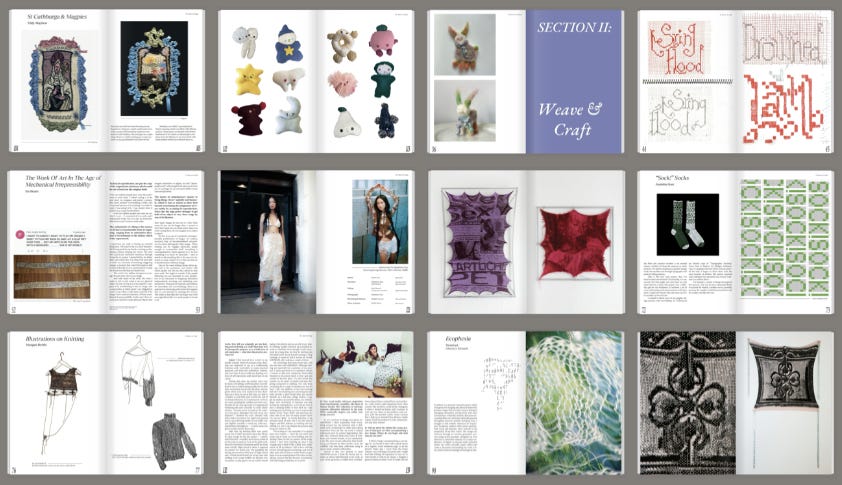

Needlebound is a zine by and for experimental fiber artists created by the brilliant knitwear designer Hayley Mortin. This interwoven collection of interviews, essays, and images with artisans and makers offers an expansive look at textile production. From artists’ soft sculptures and wearable garments to scientific experiments with bio-materials, digital tools, and wool farming, Needlebound brings together so many different perspectives on the craft, providing a valuable resource for skilled artisans and curious novices alike. In a time when our consumption of fashion and art is so influenced by the fleeting whims of social media, I appreciated how many of these stories invited readers to slow down, to think of knitting as a process more than a finished product, and to find community in these acts of creativity.

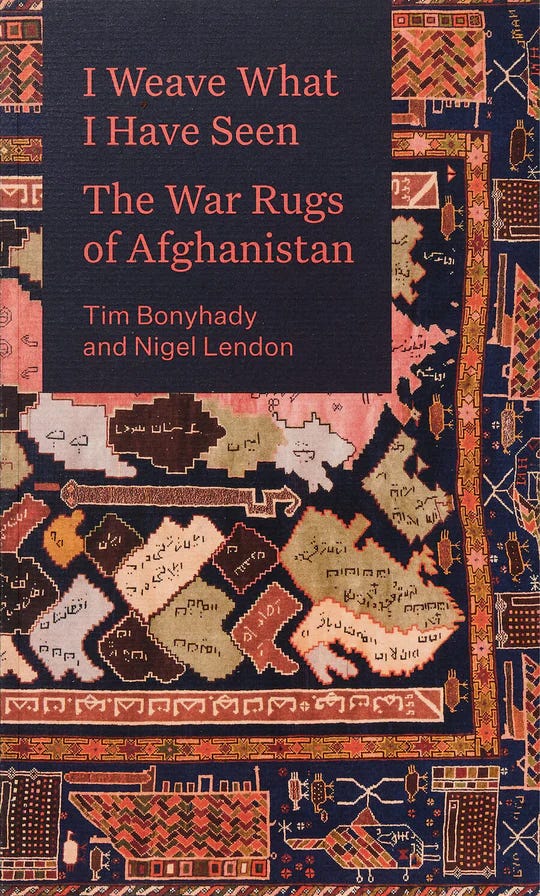

Created as as an exhibition catalog, I Weave What I Have Seen: The War Rugs of Afghanistan analyzes 40 rugs produced by Afghan weavers in reaction to the Soviet invasion of the 1970s and 80s and the United States invasion in 2001. They incorporated symbols of modern warfare into traditional Afghan iconography as armed conflicts devastated the country. Scenes of combat, weaponry motifs, and regional maps quickly became mass-produced for collectors and tourists. Each rug features detailed descriptions of their origins (such as the weaving family who made it) and of their rich iconography, providing much-needed analysis to items that were often seen as mere novelty souvenirs. The Afghan war rugs became not only a tool for political storytelling, but a resilient way to keep these weaving traditions alive.

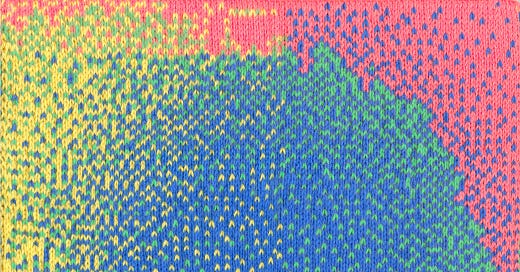

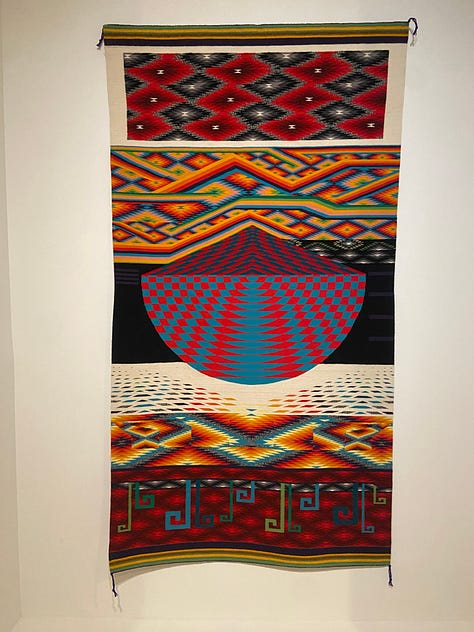

Melissa Cody is a Navajo weaver whose practice that infuses traditional Diné imagery with chromatic pixelation inspired by 1980s video games. Her show, Webbed Skies, was one of the best exhibits I saw this year. Rich geometric tapestries merge traditional craft with digital technology, with particular nods to the mid-1800s Navajo Germantown weaving technique that was born from the unraveling of blanket rations during the U.S. government’s territorial expulsion. Under Cody’s hands, weaving becomes a site for cultural experimentation and reclamation. A 4th-generation weaver, I love that the curators included a display with images of Cody at her loom, along with her wooden tools and samples of her colorful synthetic-dyed yarn.

LOOK

Ophelia Arc is a textile artist whose body work often feels more like flesh than fiber. As yarn is flayed out, bunched up, stuffed, suspended, and interlaced, it takes on a corporeal sensation, connecting the material to psychological threads of memory and trauma. Each piece has a meat-like, beautiful metabolic rot to them, suggesting cycles of unmaking, digestion, and regeneration. I could stare at them for hours (even if some are rendered so uncannily that it makes me a little squeamish. As Arc describes her process of crocheting and tapping into that muscular memory of making: “It got me thinking about the idea of a rumination loop that exists in the mind, like when you’re stuck in a thought pattern. A lot of my work applies this form of soft logic to a hard fact, and considers the paradox that happens there.”

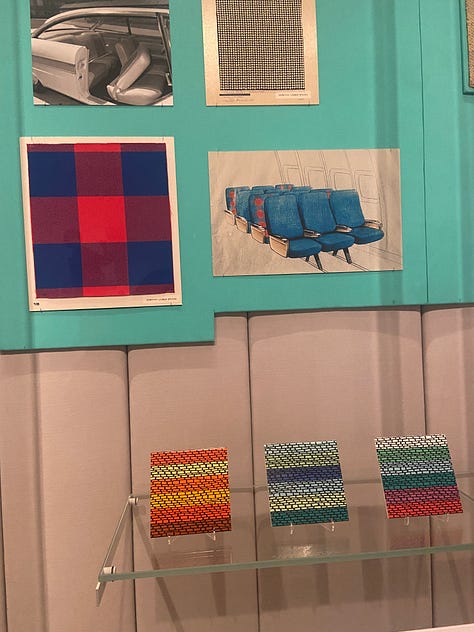

Known as “the mother of modern weaving,” textile designer Dorothy Liebes made a name for herself thanks to fabrics she produced in collaboration with people like Frank Lloyd Wright, Doris Duke, Bonnie Cashin, and companies like American Airlines, the Plaza Hotel, and Chrysler. From wall hangings to upholstery, Liebes used weaving to reshape modern interiors, film sets, and commercial design, and was a pioneer in using synthetic threads in the post-war period. In a time when most female makers would go unnoticed and uncredited, Liebes asserted herself as a powerful weaver and a transformative force in the textile industry.

Mrinalini Mukherjee’s vibrant hemp and jute sculptures tower over you, resembling a hybrid mix of organic ecological forms and something divine-like, bridging traditional Indian craft traditions and folklore with a contemporary sensibility of abstract design. Some might remind you of a blooming flower, while others an estranged humanoid figure through their layered folds and twisting forms. Each is a technical marvel, created from elaborate patterns of knotting and weaving with a dimensionality Mukherjee was able to achieve without the use of a loom.

Katya Budkovskaya is a Russian textile artist who uses knitting to make glitching, kaleidoscopic tapestries. Budkovskaya’s design process is so fascinating to me: each pattern sketch is first dropped into Photoshop where painted pixels are gradually built up to represent every stitch she will make. Her color palettes skew from pastel retro nostalgia to neon, eye-straining hues, creating fascinating optical illusions with light and shape that remind me of broken computer screens and heat maps held together by the soft weight of yarn fibers.

LISTEN

Immaterial by the Metropolitan Museum of Art explores a single material’s role across thousands of years of art history. I really enjoyed their episode on linen, a ubiquitous fabric that many of us are reaching for now during the summer. With contributions by curators, cultural critics, and fashion historians, we explore how flaxseed is woven into this material and its many uses over the years from Egyptian burial offerings to expressions of masculinity and colonial power in modern suiting.

A.G. Cook’s track “The Weave” off his recent album Britpop is a synth-y spindle of a song. There’s a soft rhythmic magic to its rolling melody and repetitive lyrics. It reminds me of working thread in between the warp of a loom, gradually building up to the image of something beautiful and whole.

Every year, Planet Money embarks on their ‘Summer School’ series, looking at moments in economic history that have shaped how we live today. Their episode, “The golden age of labor and looms,” begins in 1348 with the Black Death and eventually takes us to the Industrial Revolution to show how textile workers’ protests transformed labor power in response to the rise of new manufacturing technologies.

LICK

Recently, I attended a talk through the Tatter Textile Library on the topic of ‘Queering The Loom.’ The event featured three presentations by weavers John Paul Morabito, Indira Allegra, and Jovencio de la Paz on their creative practices. I love how each of them discussed weaving as an embodied act, one capable of untangling binaries and generating expressions of queer time, memory, and thinking through the use of beading, performance, and experiments with digital software. Tatter is a fantastic resource if you’re looking to learn about textile crafts, with hands-on workshops here in Brooklyn and a great accessible schedule of virtual lectures.

I have no idea how I’ll get there, but I absolutely need to visit the World Famous Crochet Museum in Joshua Tree. This tiny building hosts a treasure trove of handmade soft sculptures and whimsical pieces collected over the years by its founder Shari Elf (who has yet to learn how to knit and crochet herself). A delightful odd archive of woven pieces smack dab in the middle of the desert.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

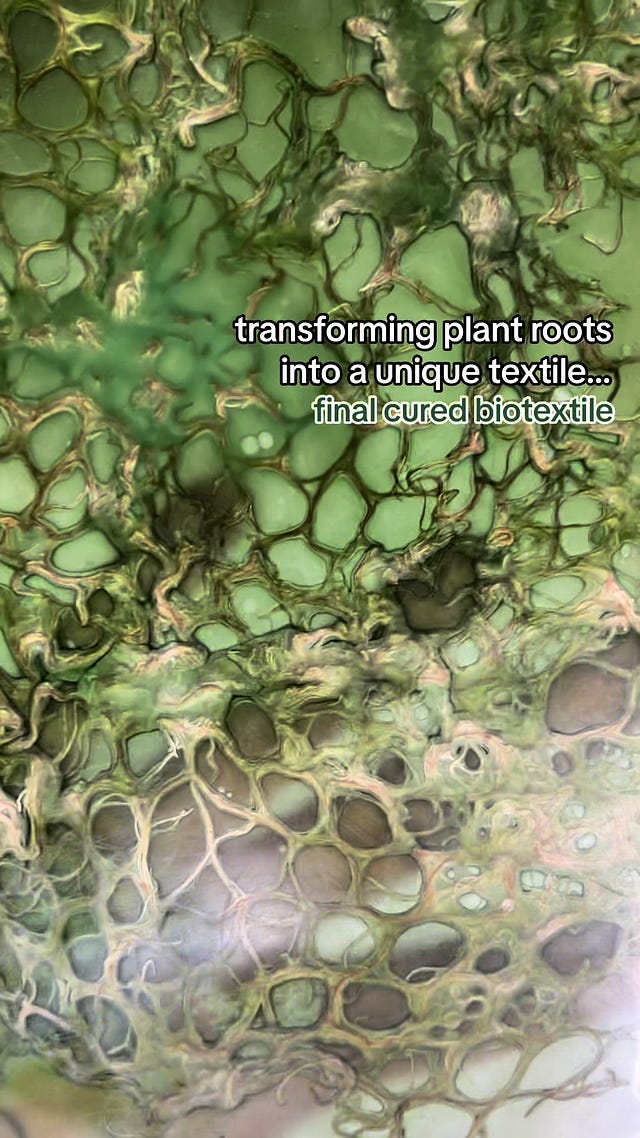

Beth Williams is a UK-based textile artist known for growing bio-yarn and textiles from algae and plants. This is some of the coolest experimental work with fiber arts I’ve ever seen, and I love how Williams meticulously documents the ephemeral process from first bloom to their spinning and knitting to decay. While pieces might only be worn or handled for a brief moment, they are thoughtfully produced and deeply cared for, evoking profound questions about sustainability and fashion consumption. Williams has also talked about how their environmental knitting practice also allows them to explore questions of accessibility and disability.

El Anatsui has gained significant acclaim over the years for his bottle-top installations, made out of aluminum caps and foil he first found when working as a professor in Nigeria. His abstract pieces are instantly recognizable thanks to their metallic, iridescent sheen. This video from Art21 documents Anatsui’s process and the tremendous labor that goes into creating these recycled compositions.

CLICK

Did you know that female weavers were employed by NASA software engineer Margaret Hamilton to make computer memory storage cores for the Apollo missions? I recently ended up in a rabbit hole about this forgotten history. Although we don’t know the names of these women, we know that they were chosen for their dexterity with this hardware and ability to recall what each line of computer code did in order to document their threading and remove errors. Hamilton (the “rope mother”) dubbed these core memory weavers as LOLs (“little old ladies”). Thanks to interventions by feminist textile artists, their legacy of technoscientific work persists today.

Back in 2022, archeologist Michèle Hayeur Smith spoke with Scientific American about her research findings that revealed the vital role of women’s weaving and textile production in the growth and expansion of Viking society. Smith gradually pieced together these histories from fabric fragments in museum collections and quickly learned how their labor at the looms contributed to the survival of their communities in harsh climates and garnered power as social and economic currency. I also appreciate that Smith (a knitter herself) often demonstrates how their looms were used, giving embodied life to the Viking women’s traditional craft.

In her piece, “At The Loom,” poet Linda Pastan invites us to come sit with her, to allow ourselves to feel the sensation of weaving through the plucking of threads, and the choreography of the shuttle, finding a fibrous musicality along the way. Pastan balances transporting us back into histories of textile creation with keeping us rooted in this intimate moment of making. Her call to create with care: “You weave a spell, / I wear it on my back, / and though the chilly stars / go bone naked / we are clothed.”