65. Fluid Reliquary

I’ve been thinking water lately. How it pools, soaks, floods, and flows. It is a force that cleans, corrodes, contaminates. Gives you life in one moment. Drowns you the next.

Hello friends,

I’ve been thinking water lately. How it pools, soaks, floods, and flows. It is a force that cleans, corrodes, contaminates. Gives you life in one moment. Drowns you the next.

As summer gradually bled into fall, I found myself contending with this liquidity. My family and I were on a road trip through the South and, after stopping at Atlanta and its famous aquarium, we found ourselves caught up in the aftermath of Hurricane Helene with washed out roads and the complete absence of water (save for some extra bottles we packed for the long drive). This year’s hurricane season was a fluidly brutal dance of shifting storm paths, great swells of storm surges, ceaseless rain, and reignited discussions of climate adaptation. I’ve also spent hours swimming laps at my local community pool this year until, exhausted and sunburnt, I’d make my way home, leaving a trail of wet flip-flop footprints and wrung out chlorine water in my wake. There’s the leak in our building’s hallway that leaves behind tiny puddles every time it rains. Rivers of smelly ooze from ripped trash bags on the sidewalk. The sticky spill of cocktails on a night out. Splattered drippings from cheap air conditioner window units. The steaming coffee and tea I consume morning and evening. Once I noticed, I couldn’t ignore it—whether the delicate beads of blood on a nicked finger or the slick gloss of wet graffiti paint I pass by on my commute.

At a recent talk I went to about coastal resiliency on the 15th anniversary of Hurricane Sandy and the influential MoMA exhibition Rising Currents, one of the architects posed this question: “What happens when you go to the water rather than retreat?”

For this newsletter, some reflections on fluidity—from exploring the materiality of this state of matter and the complex hydrological systems that sustain us to diving into waterlogged histories and the dynamic flow of being and surviving in the world.

TOUCH

No book has haunted me in recent years quite like Julia Armfield's Our Wives Under The Sea. This eerie tale (of a deep-sea researcher who suddenly returns home after she went missing on a submarine expedition) dances between the genres of the Gothic, queer romance, eco-horror, magical realism, and grief fiction. I don't want to give too much away, but I remember feeling so profoundly thirsty, yet also slick and waterlogged as I took in Armfield's surreal prose—a testament to its fluid power.

Described as “a cup of jasmine tea, brewed in ocean water,” The Point by Clue Perfumery is the most interesting subversion of marine scents I’ve encountered in fragrance. When we think of aquatics, we think of something fresh, blue, oftentimes more masculine. This blend of notes includes elements like crushed porcelain and wet sand, resulting in an androgynous scent that’s more like a briny encrusted shipwreck than your standard clean cologne. Bright and mineralic, it reminds me of that brief moment of calm when you dive under the frothy tumble of ocean waves.

Last year, I had the chance to attend a dress rehearsal for Newtown Odyssey, a contemporary opera about and set on Newtown Creek. For those unfamiliar, Newtown Creek is a 4-mile waterway between Brooklyn and Queens that has been used as an industrious port for hundreds of years. Yet generations of oil spills, metal and chemical dumping, and sewage runoff from the refineries and factories along its shores have left it so contaminated that it’s been designated a Superfund Site. When we think about climate change storytelling, we usually think of documentaries or news reports, but opera proved to be a compelling medium for telling the story of this creek, its human and non-human inhabitants, and the pressures of gentrification and clean-up shaping the composition of its water. I also loved that the Newtown Creek Alliance did a presentation beforehand (with a tank of water from the creek itself).

Duck: Two Years In The Oil Sands is a graphic memoir about Kate Beaton’s experience working in Canada's fossil fuel industry. Beaton's narrative is loaded with tensions: her struggle to sympathize with her fellow workers while also becoming the victim of sexual violence amidst this predominantly male workforce; trying to survive financially as a young person saddled with student loan debt and few job prospects while also wrestling with the morality of working at a place that is actively decimating Canada's landscape; becoming a migrant worker drifting from temporary oil field camps while also witnessing the industry's displacement of First Nations communities. Oil itself appears very little in Beaton's story, but it doesn't really need to. Beaton grapples, instead, with the undercurrents of extractive power that sustain these harmful systems that the destroy people and ecosystems who encounter it.

LOOK

I encountered Firelei Báez’s painting Untitled (United States Marine Hospital) (2019) at her ICA Boston retrospective and it’s been on my mind since. This massive painting swallows you up with its turbulent blue as you go up close to see the details at the bottom. Báez’s sweeping brush strokes are layered over a WPA architectural diagram of the historic New Orleans hospital built to care for injured seamen. The United States Marine Hospital eventually became a psychiatric facility, and prioritized mental health treatment for victims in the wake of Hurricane Katrina. Standing in front of this painting, you can’t tell if the water is the storm surge crashing over the hospital, retreating floodwaters, or a representation of New Orleanians’ collective emotional turmoil and healing trauma. Maybe the water depicts all of them.

I first saw New Public Hydrant in MoMA’s 2023 New York New Publics Show. The bright, welcoming blue of these prosthetic fire hydrant attachments made them impossible to miss as your roamed the gallery. Co-created by Tei Carpenter and Chris Woebken, this project sought to hack the city’s water infrastructure and reevaluate our relationship to this vital public utility. New York City boasts some of the best drinking water in the world, yet access to it when you’re outside can be a messy patchwork of broken fountains, sealed hydrants, and shutoff faucets. These sketches and prototypes currently include a bottle filling station, a water fountain with various heights for pets and people, a solar hot water station, and a sprinkler boombox.

Ani Liu’s 2022 sculpture Untitled (Feeding Through Space and Time) is an artwork that is in constant motion, circulating 5.85 gallons of synthetic milk across a network of tubes programmed to the rhythm of Liu’s own breast pump. The work (whose liquid quantity equalled the amount of milk Liu produced each month) came out of her experience trying to balance re-entering the labor force with the demands of her maternal care work. Liu uses these circuitous rivers to wrestle with the invisible labor of motherhood as well as the intimate relational tensions of the biological and the mechanical that emerged between herself, her child, and her machine. A great addition in the impactful lineage of breast milk as artistic medium.

LISTEN

At just 10 episodes long, Scaffold’s audio series Power & Public Space remains one of my favorites. A personal highlight is their interview with artist Lauren Bon of Metabolic Studio about her project Bending The River. Bon seeks to divert polluted water from the Los Angeles River, remediate it, and redistribute it back into a network of green spaces to help restore the area’s original floodplain. The L.A. River is notorious for its concretized flood control design, initially built in the 1930s to send city wastewater out to the Pacific. Bon provides a vital ecological intervention through adaptive reuse infrastructure that will redirect the channel’s flow back into native wetlands and local parks, creating a healthier, more sustainable relationship to urban waterways. I highly suggest pairing this discussion of Bon’s creative vision with recent updates of the project’s construction to see how it has grown.

Addison Rae’s “Aquamarine” is an absolute gem of a pop song—and one that’s been stuck in my head since it dropped a week ago. Rae’s iridescent vocals and breathy lyrics like “Swimming in the sea with the salt in my hair / Kissed by the sun, it’s a love affair / Heart of the ocean around my neck / I don’t have to say it, you know what’s next” evoke a nostalgia for the dreamy mermaid-themed imagery we all reblogged as teens on Tumblr. I remain forever fascinated by Rae’s career trajectory from cringey viral TikTok dance star to cool girl pop princess.

Depending on where you live, how you get and consume water usually means either going to the tap to refill your glasses or using water bottles and gallon jugs to quench your thirst. Food science podcast Gastropod dove into this history of personal hydration with a look over the ongoing fight between bottles and tap. What seems like a straightforward journey into bottling water for the personal convenience of portability ends up becoming a much more complicated tale of corporate greed, unsustainable consumption, the invention of PET plastics, and the environmental cost of privatizing a valuable natural resource and selling it back to us.

A while back I listened to a phenomenal interview Outside/In did with science writer Sabrina Imbler about their book How Far the Light Reaches: A Life in Ten Sea Creatures. Growing up on the coast of Florida I always knew the ocean was a diverse, strange place, but Imbler invites us to find a queer kinship with these norm-defying undersea organisms. The conversation moves from Imbler’s own discoveries (like finding jellyfish while with a trans surf club on Rockaway Beach) to bigger reflections on how we can evolve science journalism to include dynamic insights from lived experiences.

LICK

Murina (2021) is a tense coming-of-age story set on the isolated, rocky islands of the Adriatic Sea. It follows Julija, a young girl with a passion for spearfishing, as she tries to extricate herself from the suffocating control of her father. When an old family friend comes for the weekend with the promise of buying their land and turning into a luxury resort, Julija begins to clash with her parents over their conflicting desires for her future. The film uses the rich blue water and harsh landscape of Croatia’s Adriatic as an extension of Julija’s psyche, a place where she can find escape, empowerment, and freedom amidst her imprisonment in paradise.

Artist and architecture researcher Imani Jacqueline Brown’s fluid practice seeks to untangle the continuums of extractivism—spanning centuries of slavery, genocide, settler-colonialism, and fossil fuel production—in order to drive us to realize futures of repair, resistance, and collective liberation. One of my favorite projects of hers is Follow The Oil. Users can explore Brown’s maps documenting Louisiana’s oil and gas infrastructure with permit data taken from the Department of Natural Resources or learn about this polluted coastal history by following the path of a single pipeline.

Sound artist Ioanna Vreme Moser’s piece Fluid Memory (2019) is a kinetic sculpture that’s activated by saltwater. As liquids move through its glass structure, the piece is able to conform computational processes and generates patterns of flow movement as the water cycles through the system. As the salt comes into contact with copper coils, it generates sounds that reflect these rhythms of computer memory. Moser’s design draws inspiration from fluidics, a technological approach that sought to use liquid hydraulics and pneumatics to perform operations. While fluidics was popular in the 1950s, it became replaced by the electronic circuitry we know today. Moser offers us an alternative, less resource-intensive computing system where saltwater can program.

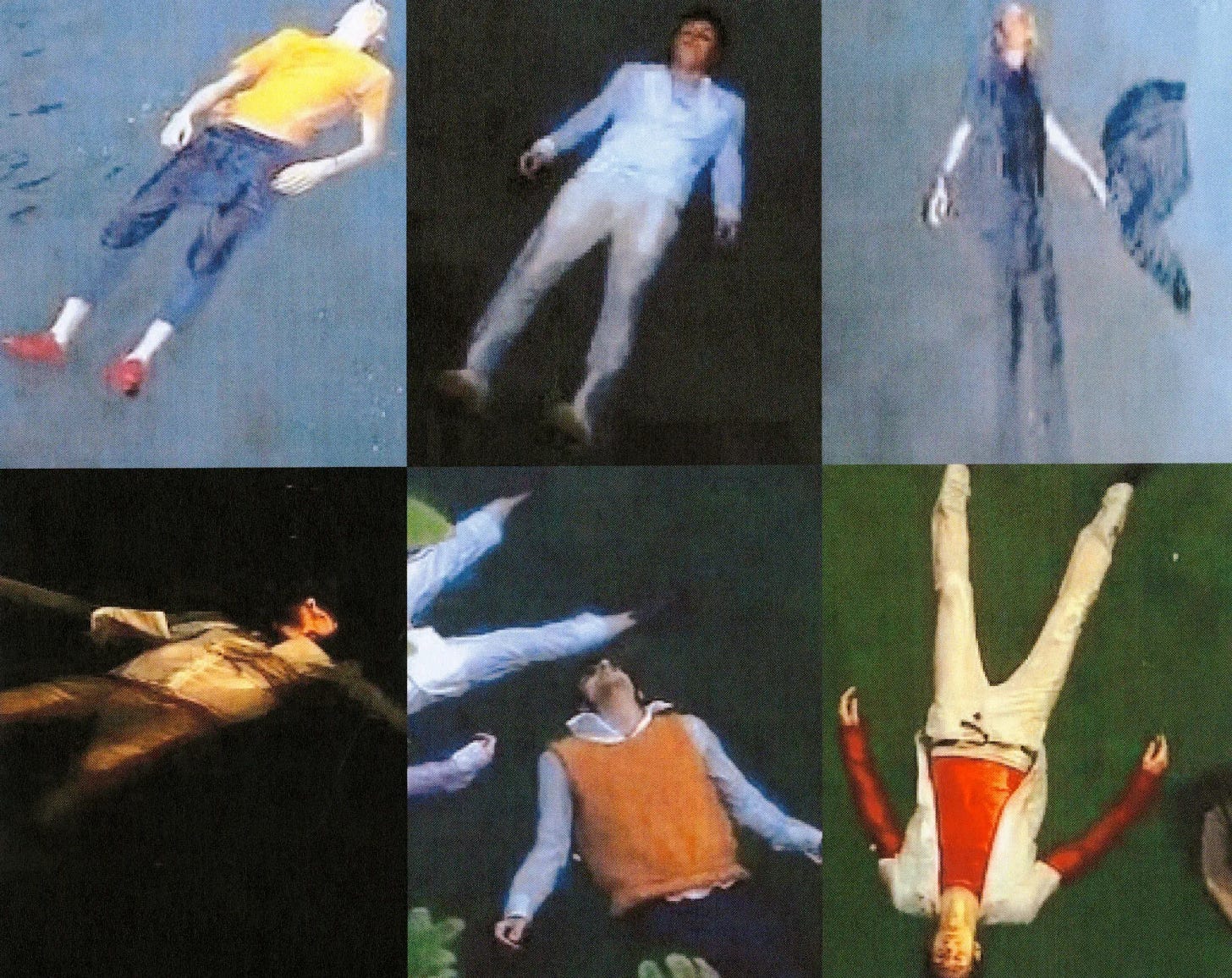

In 2003, confused attendees were shocked to find that the models for Carol Christian Poell’s SS04 show were not emerging from Milan’s alleyways or streets, but rather floating down the Naviglio Grande. Titled “Mainstream Downstream,” the presentation featured a collection soaked in the rancid, polluted water of the canal. The human models (no, they were not mannequins) kept a corpse-like stillness thanks to inflatable float supports as they went down the water. You can still find recordings of the show, and I suggest pairing it with this guide and this commemorative article.

CLICK

Walking around New York these days has me thinking of Emily Raboteau’s essay “Daylighting a Brook in the Bronx.” The five boroughs were all built on many buried creeks, streams, and lakes, but Raboteau explores one area by her neighborhood that will soon be home to one of the city’s biggest green infrastructure restoration projects. As more intense storms overwhelm our streets and sewers, Raboteau takes us on a walk to contemplate how bringing back this historic native ecosystem can usher in a new era of environmental justice after generations of harm by highway construction, redlining, asthma-inducing pollution, and the paving of green space. She writes: “The water never really went away. It still remembers where it used to be.”

Cultural historian and public servant Sergio Lopez explores the musical traditions that emerged after the devastating Great Flood of 1927 that destroyed thousands of square miles of land, killing hundreds and leaving many more displaced across the Mississippi Delta. Abandoned by the government in the wake of this horrific pain and devastation, musicians from these poor Black communities turned to song to express their traumatic experiences as refugees and remember what they lost. Lopez deftly weaves together song lyrics with historical accounts from flood victims.

Alice Towey’s short story “Dark Waters Still Flow” is told from the perspective of a sentient water treatment plant. Perhaps this is unsurprising given Towey’s background as a civil engineer specializing in water management. As NEWT regulates its everyday filtration processes, like churning digesters and sending oxygen into aeration basins, it notices things like the chill of autumn, the presence of owls and other animals along its waters, and reads poems to itself as it works. This is a delightful tale about more-than-human care and futuristic infrastructures.

There’s something so marvelous and whimsical about Amy Gerstler’s poem “Sea Foam Palace.” Here the body becomes gelatinous, porous, euphoric with sludge and slick as fleshy beings collapse and bubble into each other. I love her playful, conversation tone as she addresses her lover with an invitation for fluid mischief: “Forgive my word-churn, my / drift, the ways this text message / has gotten all frothy.”

A darn good read!