I'm sick of thinking about work. I'm tired of hearing about layoffs, watching my friends waste hours of their lives applying to jobs that will ghost them or steal their data, reading articles keen to blame the fucked state of the job market on one 'lazy' generation or another rather than the exploitative systems of corporate greed and wage stagnation that make all of us feel overworked and underpaid these days. The thought of "recession-core" and "recession-proofing" my life exhausts me. The thought of the "future of work" exhausts me more.

I've been thinking about my labor a lot these days. What do I contribute? How do I work? Who do I want to work for? Or with? It didn't take me very long into adulthood to realize I'd never be a corporate baddie or an office siren or whatever. I've never been able to hold on to a regular 9-to-5 for longer than a few months. The prospect of the same commute to the same office every day makes me feel crazy. Teams and Slack notifications make me shudder. Jargon like 'PTO' and 'ROI' make me want to rip my hair out. Yet, my time as a multi-gig worker in the art world, museums, and academia has been fraught with its own labor struggles for living wages, creative agency, and the never-ending quest for a healthier work-life balance. Even if what we all choose to do is different, our fights for dignity and survival remain the same.

For this newsletter, labor in all of its myriad messy forms. From workplace dramas to corporate corruption to overlooked histories of workers' rights, systemic sensoriums and commodified collapse and unraveling economies abound.

TOUCH

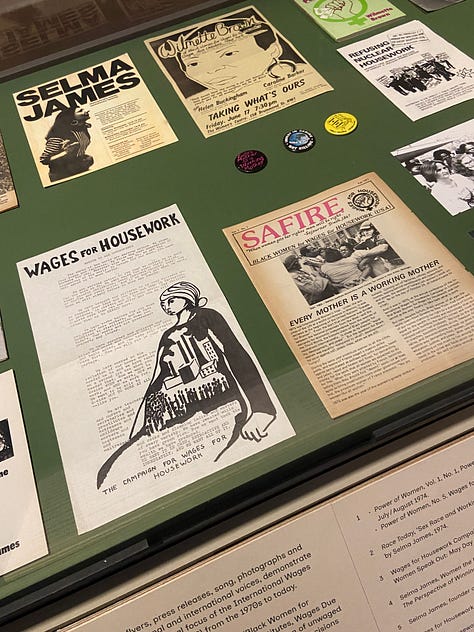

I was in London a few weeks back and saw Hard Graft: Work, Health, and Rights at the Wellcome Collection. The exhibition centers the experiences of underrepresented workers whose dangerous, marginalized, and precarious labor also invite collective healing and resistance. The show was divided into three sections: “The Plantation,” “The Street,” and “The Home.” Each looked at these sites of racialized, gendered, and classed labor from colonization to the present day. There was something so poignant about seeing these multi-generational, global struggles interconnected in this way, whether it be the fight for paid domestic work, sex workers rights, or revolting against enslavement. The show spoke not only to the toll these kinds of work take on the body, but how amplifying these stories creates a healthier world for us all.

Hiroko Oyamada’s The Factory follows three employees as they begin new jobs in a sprawling, mysterious factory campus. As they settle into their seemingly mundane roles, they begin to question the purpose of their labor and discover peculiarities about their new employer. I don’t want to spoil too much, but I love how this novella embraces the strange and surreal. Science fiction has always been my favorite genre for critiquing the modern workplace, and this is another read to add to your list.

I realize I never talk about theater on here, but I wanted to share a piece I saw a couple of years ago that still haunts me to this day. Titled Job, the play follows a therapist and his patient, a young woman Jane who had a viral public meltdown and is forced to take a leave of absence from her job as an online content moderator. Over the course of their session, as the two gradually learn more about each other, we see how Jane got pushed to the brink and how her tech job has drastically shaped her worldview. A sharp, disturbing thriller.

Last time I was in Boston, I got to catch a retrospective of the artist John Wilson. Known for works like Young Americans (1972–75) and his keen eye for portraiture, Wilson was a beloved figure in the local art scene and spent much of his career teaching at Boston University. I was struck by the focus on Wilson’s work as an artist, how his creative labor as maker and mentor reflected his political values of racial equality and social justice and his experiences with the Civil Rights Movement. Sketches and iterations of paintings, sculptures, and illustrations lined the walls, revealing his process to us. A video nearby plays clips of a community clean-up of Wilson’s bronze bust Eternal Presence (1985) at its location outside the National Center for Afro-American Artists in Roxbury. We watch as neighbors wash the statue and polish it to a shine, enabling Wilson’s artistic laboring to live on.

LOOK

In 2024, fiber artist

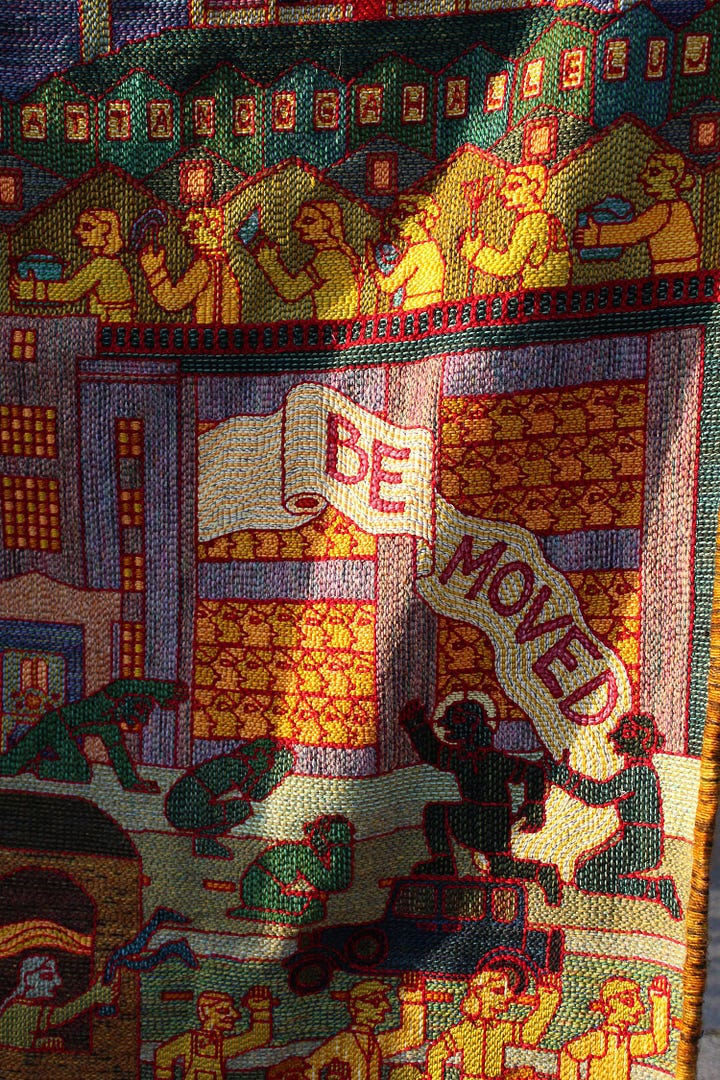

created Mill Town, dedicated to the 1934 strike by workers at the Coosa-Thatcher textile factory. Arnold’s embroidered tapestry tells their story of labor organizing and their continued fight even when threatened with brutal crackdowns. I’m struck by the ode to the protest song, We Shall Not Be Moved, which continues to be sung by activists and workers today. Arnold’s practice weaves together legacies of labor struggle and political liberation, transforming the tapestry into a documentary of lesser-known working class histories. Some other favorites? These Hands (2024) made for Volkswagen workers at IBEW Local 175 and I Walk (2025) dedicated to the 1918 Chattanooga carmen’s strike and streetcar riots.When designers Revital Cohen and Tuur Van Balen learned from a handbook for mechanical engineers that workers can sustain an output of about 75 watts over the course of an 8-hour shift, they partnered with choreographer Alexander Whitley to create the sculptural-performance, 75 Watts. This assembly line dance, performed by workers at the White Horse Electric Factory in Zhongshan, China, draws our focus not to their products, but the process of their making. Set at the center of the world’s manufacturing and global supply chain, the parts they assemble while they move are designed to support the movement of their bodies, not to create a new commodity for the market. As the artists note in an interview with MoMA: “Within the huge complexity of industrial manufacturing processes, the biological behavior of human bodies on an assembly line is not always predictable enough to fit…[This] feels relevant again in these times of neo-feudal economies and precarious labor.” Timely in this moment of trade wars, you can watch a section of the performance here.

In his ongoing series, Dark Gardens, photographer Md Fazla Rabbi Fatiq documents the complex history of tea farming across Bangladesh. When tea production began under British colonization in the 19th century, workers faced brutal working conditions and extreme weather, leading to protests that resulted in the deaths and continued enslavement of many. Fatiq charts this industry’s continuation into the present, where the afterlives of these plantations still perpetuate unsafe and exploitative working conditions. Fatiq has a sharp eye for this industry’s contrasts and contradictions: We see a worker’s hand permanently disabled after an accident in a tea-processing factory, an eye blinded from pesticides, the land aglow with fireflies, and a goat balanced precariously on terrain bare from over-harvest.

At first glance, Liza Lou’s Kitchen (1991–1996) appears to just that, an ordinary kitchen rendered in a glittering sculptural technicolor. Yet the closer you look, you’ll start to notice that this full-scale replica is decorated with thousands of hand-glued glass beads. The sheer scale of time and energy that went into making this artwork might be hard to wrap your head around, but Lou made it to acknowledge the value of domestic work and challenge the dismissal of gendered craft. By merging these two historically feminine domains, Lou invites you to reflect home, labor, and dignity.

LISTEN

“Work, work, work / Die, die, die,” Shilpa Ray croons in her song, “Add Value Add Time.” Playing off the questions posed by every MTA MetroCard machine, Ray contemplates the senseless cycle of the work commute and the futility of trying to survive in a dehumanizing economic system. The upbeat melodies under her frustrated lyrics feel like that moment when you try to smile through your anger.

Back in 2019, photographer LaToya Ruby Frazier spoke with the Modern Art Notes podcast about her series, The Last Cruze, about the General Motors’s Lordstown, Ohio plant and the UAW workers’ lives amid the plant’s shutdown. I really appreciated how Frazier talks about her process documenting this working class community’s fight for survival and their grief over the closure, challenging labor stereotypes and building in this current political climate. Not mentioned in the podcast but still interesting, the photographs are displayed in an installation that mimics the factory assembly line.

My go-to podcast recommendation is always Busted Business Bureau. If you’re looking to laugh while also learning about wild stories of companies behaving badly, corporate scams, and batshit behavior businesses try to get away with, this is definitely the show for you. A few particularly wild episodes to get you started: The Salvation Army, ShotSpotter, Toys ‘R’ Us, and Southwest Airlines.

No story of worker abuse terrifies me quite like the Radium Girls. In the 1920s, female painters at a watch dial factory started falling sick and dying of mysterious, gruesome illnesses. The cause? They had been instructed by their bosses to touch the tip of their brushes on their lips, causing them to ingest deadly amounts of radium-laced paint. Criminal goes into this dark history and goes beyond the horror of these young women’s fates to explore how their legal fight for justice impacted modern labor laws.

LICK

Of course, I have to talk about Severance. A visually-stunning thrill ride, Severance creates a scathing labor critiques of the modern workplace by immersing us in an elaborate late capitalist sci-fi dystopia. For the uninitiated: the show follows a team of workers who have undergone a procedure to separate their work selves from their outside selves. As we follow these “innies” and their mysterious tasks at the sinister biotech corporation Lumon Industries, we wrestle with issues of bodily autonomy, workplace organizing, and corporate greed. Having just finished its second season, the show delved into even deeper, more nuanced explorations of Lumon as a metaphor for mega-companies we know today, from the aftermath of company towns to racist respectability politics. Highly recommend pairing your watch with discussions about the show’s office and corporate design.

If you’re looking for breaking news about ongoing labor issues and investigations into harmful companies and economic policies, I can’t recommend More Perfect Union enough. This platform first got on my radar when Starbucks workers were striking and unionizing a few years back. I remember noticing that they were one of very few outlets who actually went out there to speak with workers, asking about their demands and their lived experiences, and I’ve kept up with their journalism ever since. With focuses on topics like climate, rural America, and corporate accountability, they have an admirable dedication to sharing workers’ stories and shedding a light on underreported, overlooked parts of the working class economy.

I first watched Barbara Kopple’s 1976 documentary Harlan County, USA for an Intro to Film class in college and was forever changed after. The film follows Kentucky coal miners on strike and the company’s attempts to break them with police, scabs, and hired agitators. Kopple’s style of nonlinear narrative that merged interviews with archival footage, jumping forward and back to explore internal political drama and corruption at United Mine Workers, and her inclusion of local folk songs and the experiences of the miners’ wives in sustaining the strike help place the struggles of Harlan County within a larger, significant continuum of American labor history.

The time I spent in my local mall’s Wannado City felt like a fever dream. Kids running around roleplaying different jobs like airplane pilot and dentist and fire fighter in a playground version of the grown-up world. I was reminded of this bizarre phenomenon in a video essay by Defunctland. This episode explores the rise of the ‘kid city,’ their absurd logistics, the corporate sponsorships that helped sustain these projects, and the eventual downfall of these playsites in the Great Recession. The hilarious archival footage of kids acting out serious jobs like lawyers is worth a watch.

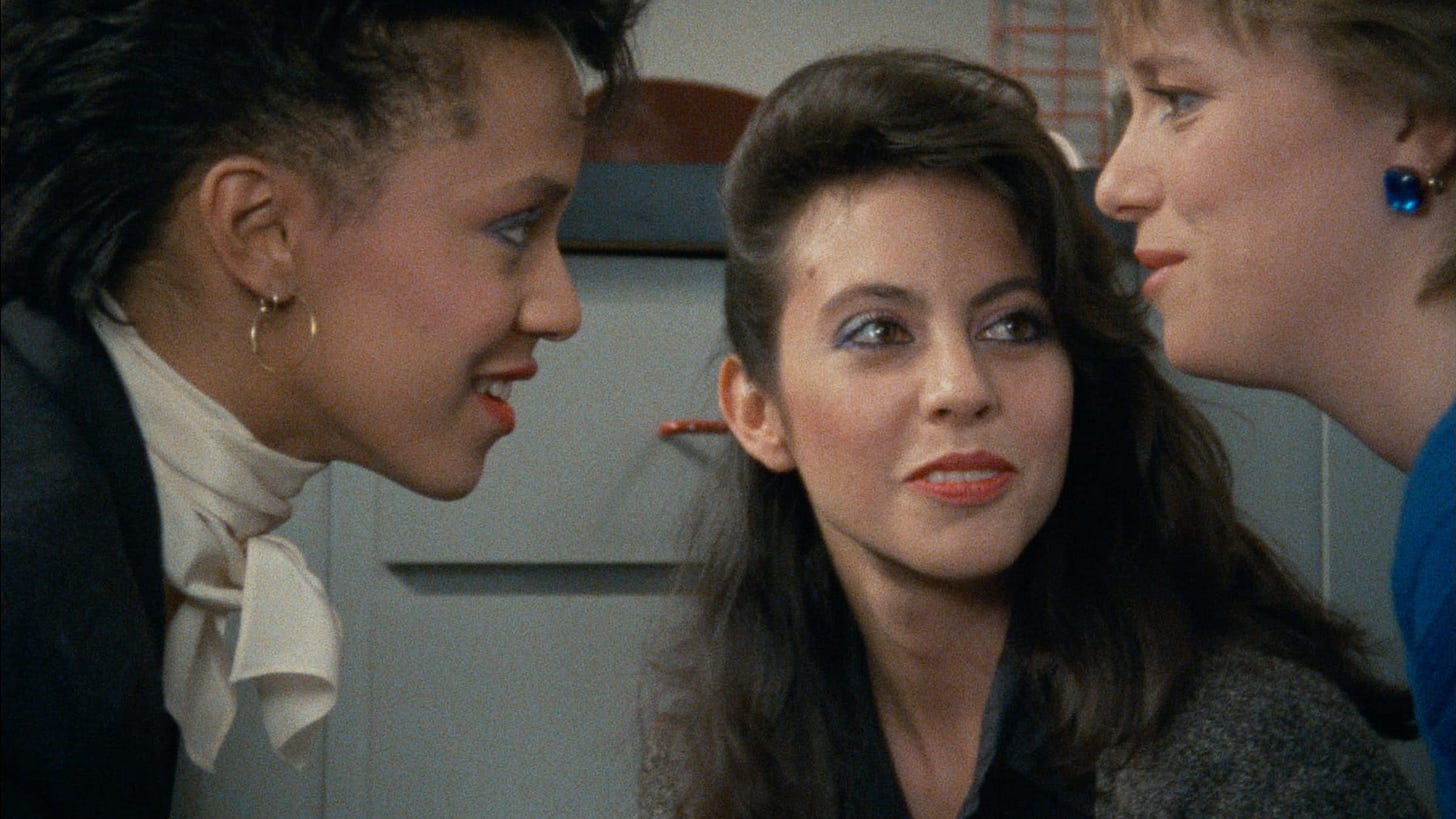

Lizzie Borden’s 1987 film Working Girls follows several women working their shift at a brothel in Manhattan. Set mostly within the confines of the loft, we watch as they interact with clients, chat in between sessions, and determine how they value their labor in a freelance economic system that would sooner exploit them. The women all find ways to reclaim their agency and push back against the capitalist greed of their madam, such as encouraging each other to pursue their dreams and mis-reporting sessions in the brothel’s ledger. Yet we also see how they are repeatedly disrespected as workers, being made to pay for their condoms, pressured to stay overtime, and, in the case of Black sex worker Debbie, told that her race will mean less pay than the other girls. By turning her feminist perspective to an industry that is so heavily stigmatized, policed, and rendered invisible in America, Borden tackles the dehumanization of sex workers with a deep care for their lives and their labor rights.

CLICK

Amidst the Oscar buzz, I really appreciated reading Marla Cruz’s critique of Anora in Angel Food. For all of the film’s praise for its dark comedy and charismatic acting performances, Cruz brings a different a perspective to the film’s narrative arc based on her own experience as a sex worker, finding frustration and triggers in the physically and emotionally violent ways Ani is treated throughout the film. Regarding the film’s labor critique, Cruz notes, “Hypnotized by dreams of assimilating into the capitalist class rather than toiling to entertain them, Ani miscalculates the boundaries between herself and her labor at her own peril.” Where Baker might have had opportunity for greater complexity, Cruz laments that “boundary between Ani the person and Ani the worker” is rendered inaccurately non-existent and that “Anora embodies the dehumanizing consumer fantasy of a devoted worker who loves the consumer so much she does not conceive of her servitude as labor.”

Back in 2013 for Strike!, anthropologist David Graeber coined the term “bullshit jobs” to describe a new kind of phenomena where, rather than seeing the reduction of working hours as technology advanced, we’re now taking on paid roles that appear to just take up time in our day with little meaning or contribution to a company’s operations. “How can one even begin to speak of dignity in labour when one secretly feels one's job should not exist?” he writes, “How can it not create a sense of deep rage and resentment.” There’s a Kafka-esque pointlessness Graeber alludes to, one that feels especially relevant in this moment where senseless layoffs and a terrible white-collar labor market have caused many to reflect on the purpose of their work.

Anna Wiener recounted her experience working at a Silicon Valley start-up for n+1, and this piece eventually grew into her memoir, also titled Uncanny Valley. As someone who grew up witnessing the wealth of the tech boom and now its decline, I appreciate how Weiner reflects on employees’ anxieties about company culture, the precarity of their jobs, and their uncertain futures. Weiner renders the tech industry’s chaotic unprofessionalism and rampant misogyny in searing detail. “They need to know: Am I down for the cause? Because if I’m not down for the cause, it’s time,” she muses, “They will do this amicably. Of course I’m down, I say, trying not to swivel in my ergonomic chair. I care deeply about the company. I am here for it.”

At last, we conclude with a poem: “13 Questions For The Next Economy” by Susan Briante. Although originally published in 2018, there is something so prophetic about Briante’s contemplations on the current economic state of the world and the radical possibilities of working for better future in the face of system that seek to destroy us. Lately, I’ve been sitting with lines like “What revolution will my daughter feed?” Observing a sign begging for diabetes test strips and advertisements for help navigating Social Security benefits, she wonders, “Who will read / this / in the next economy, the one that comes after the one that kills us?”

Many thanks!

Thought provoking and compelling rumination 🙏