Like many of you, I spent last Wednesday in a daze of fury and disappointment. As I’ve spent the past week recalibrating, checking in with friends, continuing my work in mutual aid, and preparing myself for the oppressive chaos that lies ahead, I found myself refusing despair and channeling that impulse for hopelessness into a productive anger built on love and care for each other.

Over this week, I’ve been turning to art to find moments of beauty, resilience, and resistance through this turbulence. Artists like Ana Mendieta, David Wojnarowicz, Jeffrey Gibson, Wendy Red Star, Sonya Clark, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, and Christine Sun Kim have lessons for us to learn and stories to tell. Even if these works were not all created in the present moment, the stories of struggle they tell and the lessons of liberation they share address feel especially urgent.

Thornton Dial, “Don't Matter How Raggly The Flag, It Still Got To Tie Us Together,” 2003

Thornton Dial was born the child of sharecroppers in Alabama, gradually becoming a painter, high construction crew member, pipe fitter and metal worker over the course of his life. In his free time, he began to make complex, bold sculptural assemblages from cloth, wood, and metal scraps he’d find, painting with abstract allegorical brushstrokes that confronted American histories of racial oppression. In his own words: “My art is the evidence of my freedom.” It’s hard not to think about the symbolic weight of flags in this present moment, but Dial’s re-interpretation provides a much-needed disruption to nationalist power through destructive entanglement.

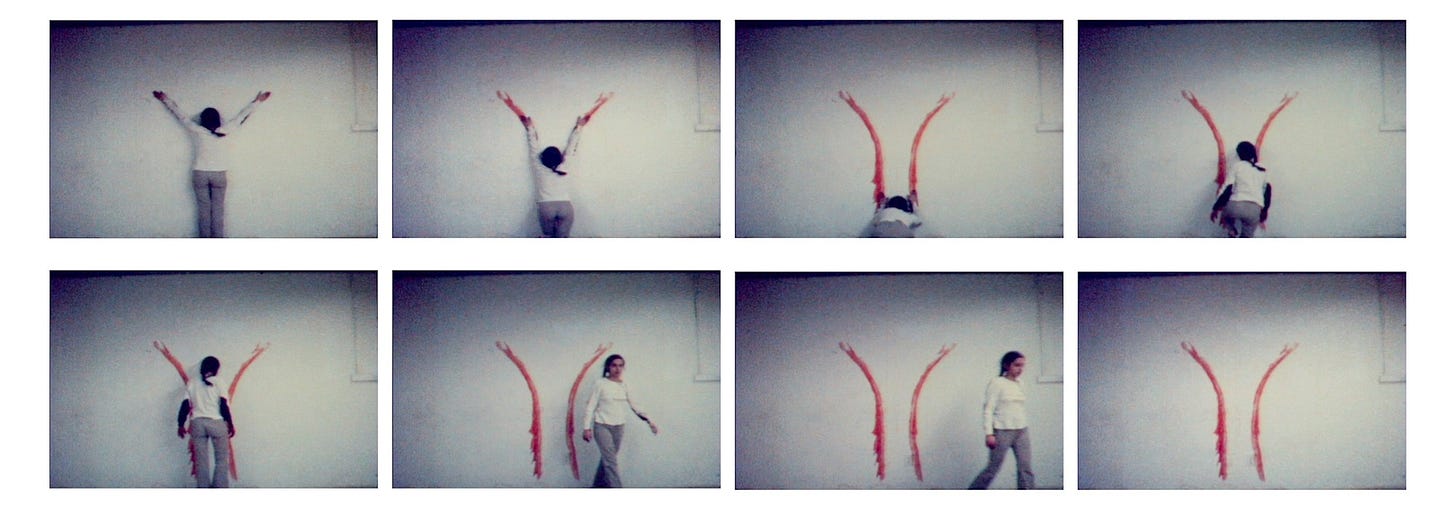

Ana Mendieta, “Untitled (Blood Sign #2 / Body Tracks), 1974

Ana Mendieta was no stranger to using blood in her work. Its eye-catching materiality represented a number of fluid political and cultural contradictions of death, violence, and healing visceral life force. Mendieta spent much of her practice experimenting with the body through gender play and her earth-body works. The year before this piece, she staged performances in response to acts of sexual and physical brutality against women. Her body tracks are acts of visceral creation. The traces of her blood-soaked arms could represent a sprouting tree or gruesome sacrifice.

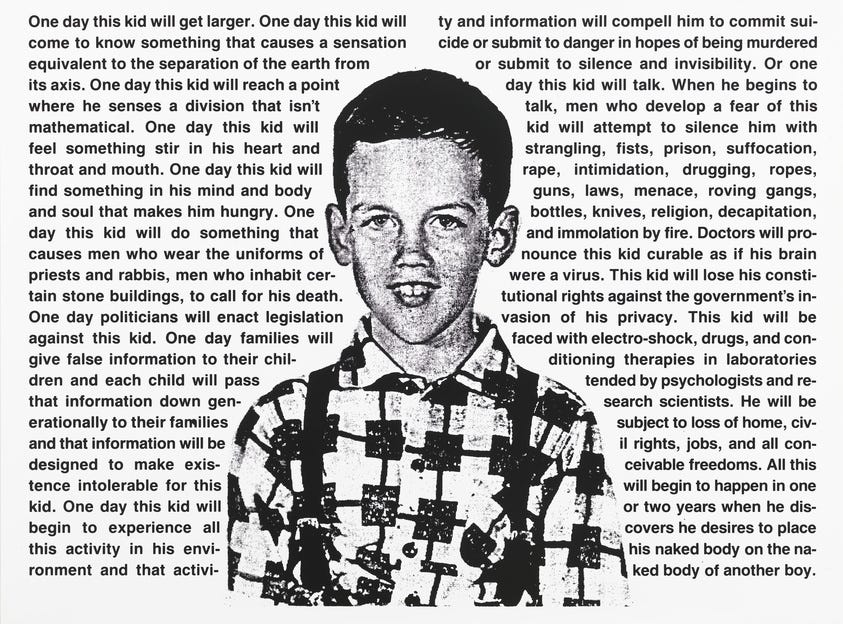

David Wojnarowicz, ““Untitled (One Day This Kid…),” 1990

I remember seeing this piece for the first time at his Whitney retrospective. Standing there, swallowed up by the portrait of David Wojnarowicz as a child, you can’t help but seek out the subject’s hopeful, smiling innocence. As you take in the words framing him, you begin to read about how the artist and AIDS activist will eventually have to confront homophobic violence, political oppression, and being socially ostracized for his sexuality. It’s an important reminder that we do not just fight for ourselves. We fight for the next generation to have a better future, too.

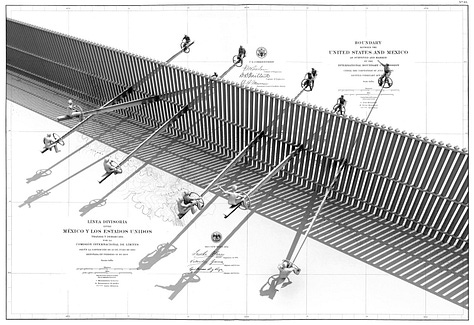

Ronald Rael and Virginia San Fratello, “Teeter-Totter Wall,” 2019

All of the anti-immigrant rhetoric thrown around this past election cycle made me incredibly nauseous. What does give me hope, however, are radical interventions like Ronald Rael and Virginia San Fratello’s Teeter-Totter Wall. Rael and Fratello have spent several years designing ways to challenge the oppressive, divisive violence of the border wall, and this one welcomes children on both sides of the harsh partition to connect with their separated families and play with each other.

Jeffrey Gibson, “OUR FREEDOM IS WORTH MORE THAN OUR PAIN,” 2017

Jeffrey Gibson uses elements of Choctaw and Cherokee beading tradition to redesign garments, punching bags, flags, and wall-hangings with punchy, colorful messages of Indigenous power and cultural resistance. There is a beautiful catharsis to these provocative pieces, the reflections they incite with their sculptural title, and their authoritative assertions of Native resilience under threat of colonization and genocide.

Tabitha Arnold, “These Hands,” 2024

I first became introduced to

’s political textile art through her piece Mill Town, about the 1934 Textile Workers’ Strike. I’ve since been thinking about the tapestry she made for IBEW Local 175 ahead of a vote to unionize at a Volkswagen plant. During the work’s creation, Arnold reflected on histories of interconnected struggles for labor rights and social justice she memorialized in the piece, and got to observe the workers see themselves represented the artworks when it was unveiled. As Arnold wrote in an essay about the piece, “But the antidote to fear is solidarity.”Tourmaline, “Salacia,” 2019

In 2019, Afrofuturist artist Tourmaline released Salacia, a short historical-fiction film set in Seneca Village. Once a thriving free Black community in the heart of Manhattan, Seneca Village was destroyed in 1855 to make way for Central Park. Tourmaline transports us back into that time with trans woman and sex worker Mary Jones as her protagonist. Jones was a real person, jailed in 1836 for stealing and quickly became a salacious tabloid sensation. Rather than centering Jones’s brutal incarceration, Tourmaline reimagines her as a resident of Seneca Village, and interweaves this story with archival footage of trans activist Sylvia Rivera. Where generations of systemic oppression aim to wipe out Black trans histories, Tourmaline seeks to develop important new intergenerational lineages. The film isn’t currently online, but you can listen to the artist talk about the film here or read about it here.

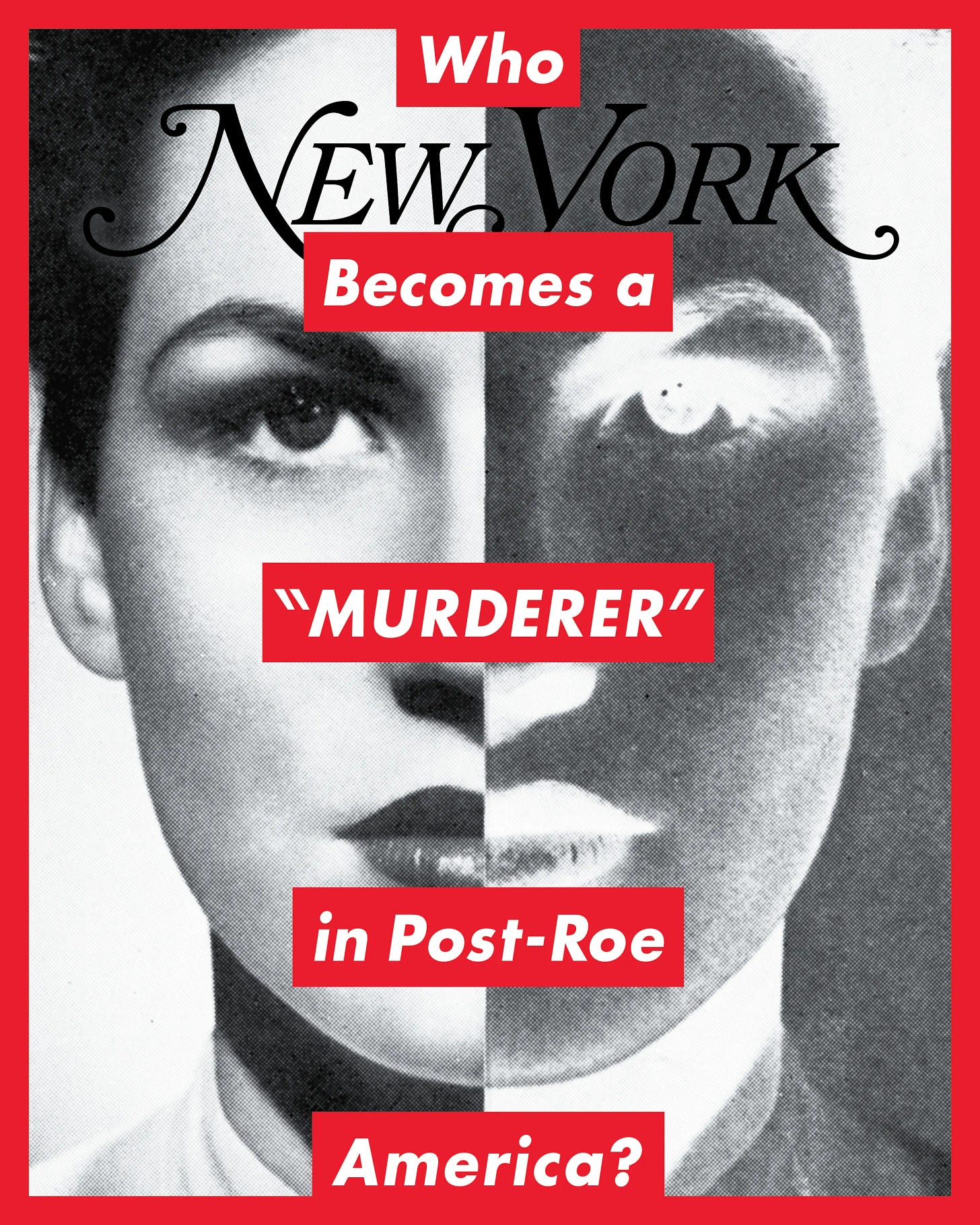

Barbara Kruger, “New York Magazine Cover, “ 2022

This piece was one of the first saw in the immediate aftermath of Roe v. Wade getting overturned. I still think about it now two years later, in the wake of traumatic stories of mothers miscarrying in hospital parking lots, some even dying under restrictive abortion bans, those crossing state lines to seek care, and pregnant people getting criminally investigated for the loss of their fetus. Barbara Kruger put this new text over her 1989 iconic work, Untitled (Your body is a battleground). In a time when rights to bodily autonomy and medical privacy are being violently ripped away, those most vulnerable will bear the brunt of the punishment and the blame.

Miguel Luciano, “Shields / Escudos,” 2020

Puerto Rican artist Miguel Luciano turned sections of decommissioned school buses into protest shields emblazoned with the black and white Resistance flag that has gained popularity on the island. Luciano’s choice of medium reflects the impacts of the territory’s ongoing fiscal crisis that has led to the closure of schools, the collapse of infrastructure, and new waves of anti-government protest. Luciano explains: “The metal bus armor that once protected children while in transit to local schools are here repurposed into protest shields to protect those fighting for the future of our children’s education, and for our right to be self-determined, and free.”

Wendy Red Star, “The Soil You See…,” 2023

Last year, Wendy Red Star installed a sculpture on the National Mall. The piece was commissioned by Monument Lab, a public history nonprofit that reimagines monuments as opportunities to uplift values of justice, equality, and democracy. While she’s known for her photographs that challenge Indigenous stereotypes, this blood-stained fingerprint reflects Red Star’s interest in the difficult legacies of treaties Indigenous tribes signed with the American government. Tribal leaders signed these documents with their prints and Red Star inscribed this memorialized gesture with the names of several Crow nation chiefs who brokered treaties between 1825 and 1880. This sculpture was placed by the Signers of the Declaration of Independence Memorial, raising further reflections on how Native peoples have been forced into land dispossession, displacement, and assimilation.

Sonya Clark, “Unraveling (Performance),” 2015-ongoing

Since 2015, artist Sonya Clark has invited museum visitors and gallery viewers to join her in undoing the durable cotton fibers of the Confederate flag. It is a physically and psychically challenging form of labor, with the cloth acting as a potent symbolic metaphor for the persistence of white supremacy until it becomes nothing more than piles of red, white, and blue thread. As she told the Nasher Museum, “[I’m] more interested in picking apart and undoing and understanding the fabric of our nation and trying to really understand the roots of racial injustice.”

Justin Brice Guariglia, “Climate Signals,” 2018

It was surreal to hear climate change come up so little during the election, especially after brutal hurricanes and a warm autumn affected the country. This absence reminded me of when Justin Brice Guariglia set up solar-powered LED highway signs around New York. The provocative pieces were meant to act as warnings, conversation starters, grabbing the attention of anyone passing by. Messages ranged from “Fossil Fueling Inequality” to “Climate Denial Kills.” Brice’s project continues evolving, with more eye-catching site-specific highway and marquee installations.

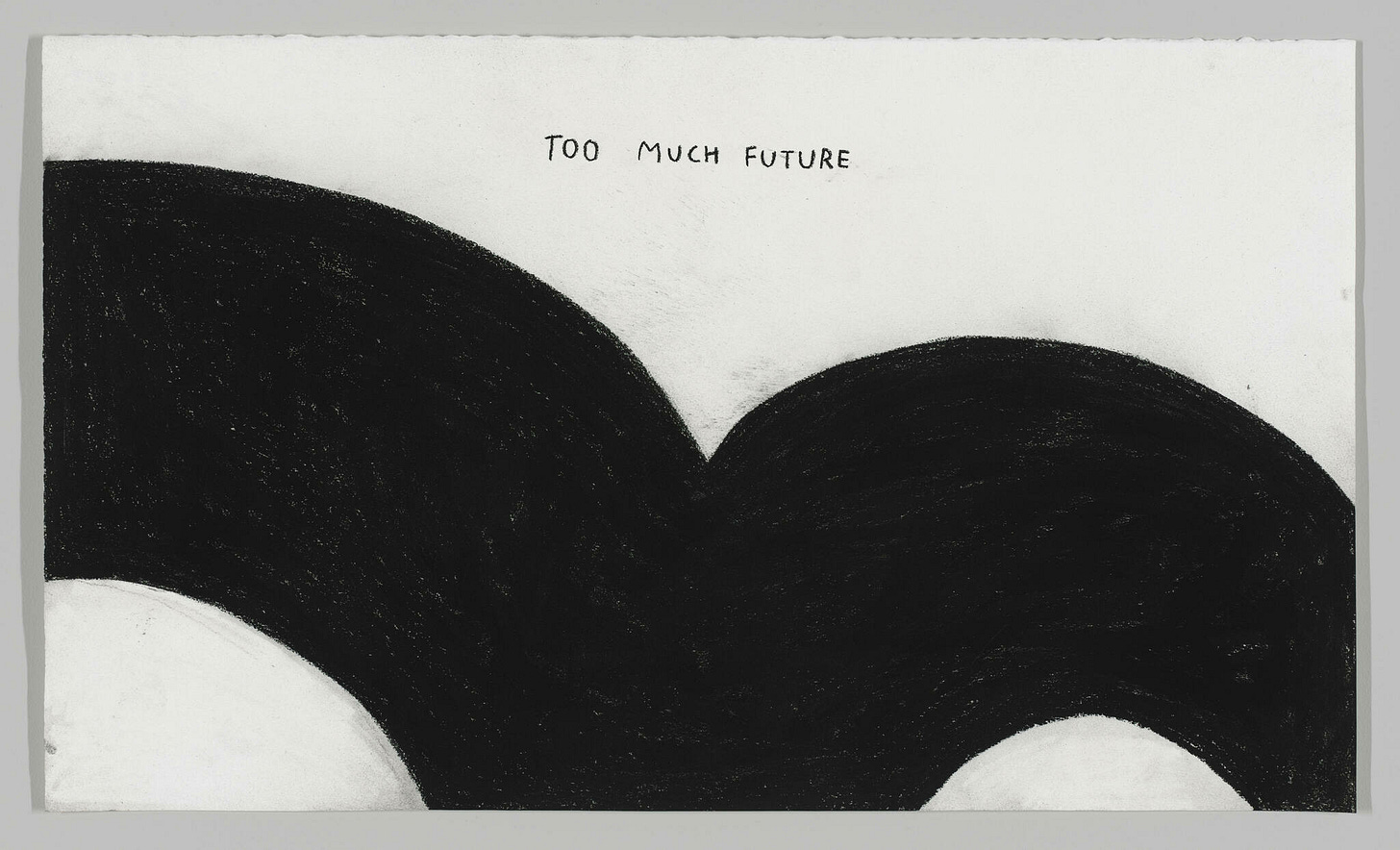

Christine Sun Kim, “Too Much Future,” 2017

There are two versions of Kim’s artwork: the initial charcoal sketch and the public billboard that once sat across the street from the Whitney. A deaf visual artist, Christine Sun Kim is known for her practice that merges ASL with musical notation and bodily gesture. Created in a tumultuous political climate, Kim emphasizes this sense of uncertainty by thickening the normally thin line that represents the sign for “future” and re-shaping it to mimic the hand movement. In a later interview, Kim noted, “When thinking about deafness and/or disability, this 'struggle' is a social construct. It is other people that make us have barriers and face issues.” How can we confront these obstacles and imagine alternative, more inclusive futures?

Felix Gonzalez-Torres, “Forbidden Colors,” 1988

Known for his heart-wrenching paired sculptures of queer love and grief, this under-discussed Felix Gonzalez-Torres unfortunately still retains its relevance. At the height of the AIDS crisis, Gonzalez-Torres drew connections between the censorship and stigmatization of gay communities and the Israeli military’s ban on the colors of the Palestinian flag. In the artist’s words: “This work is about my exclusion from the circle of power where social and cultural values are elaborated and about my rejection of the imposed and established order.” I’m reminded of the jarring moment outside the DNC where attendees plugged their ears to avoid hearing protestors read the names of dead Gazans and when a Muslim speaker was ultimately prevented from giving a speech at the convention. I am thinking about how Gonzalez-Torres refused the complicity of silence then, and how we should continue to refuse it now.

Firelei Báez, “On rest and resistance, Because we love you (to all those stolen from among us),” 2020

I’ve been thinking about this Firelei Báez painting since I first saw it at the ICA Boston earlier this year. This piece embodies the current moment for me, a time for us to care for ourselves while also not losing sight of the political and economic devastation looming ahead. Recently, my social media feeds have been full of people sharing passages from the Octavia Butler book Báez’s subject is reading and identifying parallels between the 1993 sci-fi dystopia and today’s turbulent racial division. In a time when we’re all burnt out, resting feels like a radical political act.