“The opioid crisis is, among other things, a parable about the awesome capability of private industry to subvert public institutions.” — Patrick Radden Keefe, Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Dynasty

Author’s Note: This essay contains discussion of suicide and substance abuse.

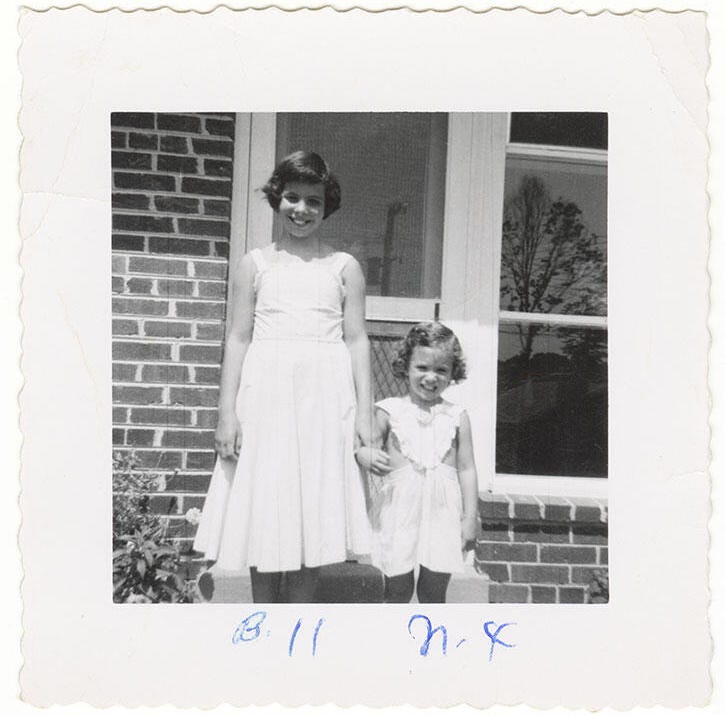

All The Beauty and The Bloodshed begins, as many documentaries about famous artists do, in childhood. But the film does not open with photographer Nan Goldin’s younger years. We begin instead with her sister Barbara, and the tumultuous events that led up to her suicide when Nan was just twelve years old.

As we move through pictures of the family with dressed-up smiles, shots of the Goldins’ neatly manicured suburban home, and Barbara and her baby sister playfully grinning at the camera, Goldin’s voiceover betrays the painful truths behind these nostalgic scenes: that Barbara had refused to conform, that she may have been queer, that she had wanted so badly to be loved by her parents, that she was constantly sent away. To be honest, this wasn’t how I expected a film about Goldin’s addiction recovery and ongoing activism against the Sackler family to open. Yet this is where All The Beauty and The Blood’s power lies, in director Laura Poitras’s careful drawing out of ghosts from the past to reveal how they still haunt our present.

The Sackler family, who amassed their tremendous fortune through Purdue Pharma’s sales of Oxycontin and the company’s role in the prescription opioid crisis, is the film’s silent specter. While the Sacklers and their lawyers deny Poitras’s interview requests, the family’s titanic presence still makes itself known. Regardless of your involvement or interest in arts and culture, odds are you’ve entered into a building or exhibition space developed with Sackler money. Once you notice them, the names of Arthur M. Sackler, his daughter Elizabeth, and other members of the Sackler Trust become impossible to ignore, mounted on signage in art galleries, emblazoned in front of education centers, included on display boards with the names of top donors.

The Sacklers’ profound philanthropic influence became the central focus of Goldin’s activist group, P.A.I.N (Prescription Addiction Intervention Now). First launched in 2017 from a support network of people in recovery or who had loved ones impacted by opioid addiction, P.A.I.N quickly gained attention for its disruptive protests at the Met, the Guggenheim, the V&A, and others. Goldin noted in a 2018 essay for Artforum that P.A.I.N’s goal is to hold the Sacklers responsible: “To get their ear we will target their philanthropy. They have washed their blood money through the halls of museums and universities around the world.” The practice of wealthy donors using art to cleanse their reputations is nothing new. Yet P.A.I.N’s direct actions and list of demands for institutions to refuse Sackler donations and take down their names marked a new chapter in ethical museum practice and institutional accountability.

I’ll admit, as someone who’s currently studying and working in museums, this was a hard movie to watch. Not only because of Goldin’s turbulent life (which I had some familiarity with as a fan of her work), but because of how painful it was to see these museums respond to P.A.I.N’s protests with mostly silence. At one point, we see leaked WhatsApp messages from a group chat of Sackler family members following one of P.A.I.N’s protests, including one from Marissa Sackler: “I speak regularly with dia on all of this and they fully support us and think Nan Goldin is crazy.” Beyond the cold dismissal of Goldin’s concerns as just another loony artist, Marissa’s note about Dia Art Foundation embodies the exact problem P.A.I.N sought to challenge.

Donors like the Sacklers have weaponized their wealth to gain private power in the art world and shield themselves from public scrutiny, while museum leaders have been actively complicit in this system of sanitizing reputations in exchange for funding. The Sacklers’ influence goes beyond galleries, too. We listen to interviews of P.A.I.N members being watched by someone parked outside Nan’s house, and even see a video they recorded of a man they believed to be hired by the family. We hear the anxiety in Nan’s voice as she recalls bracing herself for a potential lawsuit and the loss of the creative reputation she worked hard to gain. We learn that the Sacklers used Purdue Pharma’s bankruptcy settlement to avoid future personal liability.

Even as removals of the Sackler name and refusals of donation are celebrated by P.A.I.N, it’s clear that the rot at the heart of today’s philanthropic system goes beyond one family or one name on a wall. It’s a whole cultural and economic system designed to buy access and protection, keeping museums in a constant state of precarious reliance on the whims of funders. That these biographical acts of Goldin’s life span the HIV/AIDS epidemic, the opioid crisis, and the COVID-19 pandemic is a reminder that these histories of cultural and medical injustice are so deeply entangled and still ongoing. Poitras’s cyclical structure to this film reminds us that the past never stays quietly in the past. History always comes back to haunt us.

But this documentary isn’t about the Sacklers (there are already plenty of those). It’s about Nan Goldin and the creative life she built for herself through the family she’s found over the years. In the face of all of this disillusionment with the art world, the failure of institutions to act ethically, the knowledge that the Sacklers’ fate remains unjust, that Barbara Goldin’s fate could have been avoided, the power of community cuts through that darkness like a flash set off a lightless room.

Although many of us have encountered Nan’s photographs on a gallery wall, in social media posts, or in book form, Goldin’s practice has always centered around the slideshow. Early in the documentary, she sits with Poitras in her studio, advancing through her life from one image slide to the next. As she recounts how she picked up a camera for the first time and immersed herself in the vibrant queer communities of Boston, Provincetown, Berlin, and New York City, we learn that she let her subjects pick the portraits they liked and tore up the ones they didn’t. When she showed The Ballad of Sexual Dependency at galleries, her friends would see themselves and comment on the pictures, enabling Nan to alter each presentation of The Ballad to fit her curatorial instincts and the feelings of those she photographed. These deeply personal histories imbued in Goldin’s work can be so easily lost in the acquisition of a single image or a descriptive wall text, and I’m so grateful for Poitras’s inclusion of those anecdotes. Even as many of Goldin’s friends succumbed to HIV/AIDS—leaving her as one of the few survivors in a decimated generation of artists—Poitras shows how they live on through Nan’s photographs and P.A.I.N’s ethos.

Every time some kind of wrongdoing is exposed, the art world asks itself the same old question: can we separate the art from the artist? Now this question has a new permutation: can we separate the donor from the source of their money? Goldin and Poitras argue that it’s impossible. Art institutions aren’t neutral islands operating separately from society; they reflect economic, sociocultural, and political values in the work they display, their funding, and infrastructure. As Poitras intercuts scenes of Goldin’s early life with her decades later in addiction recovery hosting P.A.I.N meetings in her living room and leading die-ins in galleries, we see how these forces of resistance, found family, and raw vulnerability have shaped her creative life and activist legacy. The personal and the political cycle into each other like flickering slides. All The Beauty and The Bloodshed is a necessary intervention in these timeworn debates of institutions, culture, and power, reminding us of art’s radical potential to confront, call out, build up, break down, and unite us all in love and heartache.