Making Perfumes In A Medieval Monastery

How I spent my Sunday at the Met Cloisters

“In a world sayable and lush, where marvels offer themselves up readily for verbal dissection, smells are often right on the tip of our tongues—but no closer—and it gives them a kind of magical distance, a mystery, a power without a name, a sacredness.” — Diane Ackerman, A Natural History of the Senses

Every time I do that meandering hike up to The Cloisters through Fort Tryron Park, I like to pretend I’m in the scene of an Anne Carson poem. With one single exception during the 9 years I’ve lived in New York, I only go to The Cloisters in the dead of winter. Like Carson’s narrator on the moors, I trudge against the biting wind, making my way over circuitous slopes lined with threadbare trees, up slippery stone staircases amidst jutting boulders, and along cliffside overlooks rendered sepia and ashen.

By the time I make it up to the entrance to the building—whose monastic tower and hourly clock chimes feel so utterly out of place in a city of pavement and skyscrapers—I’m already a few minutes late to the perfume-making workshop.

We begin in the dimly-lit galleries where some of the most prized objects in The Cloisters’ collections are held: The Unicorn Tapestries. If you’ll permit the art historian in me to geek out, these are a marvel not only for their beauty (and the fact that most of the cycle managed to stay completely intact since its creation in the 1500s and subsequent rediscovery in a barn in the French countryside during the 1850s) but because these textiles offer a fascinating insight into botanical knowledges and mythic symbolism in everyday life during the Middle Ages. Take the unicorn, for instance. Although scholars still debate its symbolism, the portrayal of its hunt suggests allegories of marriage and fertility. Unicorn horns themselves were believed to purify water and offer protection from poison (a silver goblet made of narwhal tooth sits nearby, sold to wealthy aristocrats as genuine unicorn horn).

Today’s workshop, however, begins with a lecture about all of the different plants and botanical imagery that surround these scenes of the unicorn. Instructor, perfumer, and expert in medicinal plants in the Middle Ages Michael Nordstrand walks us through some of the tapestries’ identified species that were also used in early perfumery.

You have common flowers like irises and lilies. The more herbaceous French centifolia rose is also present in the tapestries, and were often grown in monasteries and castle gardens. Nordstrand also pointed out a bitter orange tree. Bitter oranges were first introduced to Europe in the 10th century by Moors living in Spain (which is why they’re also known as Seville oranges). Although the raw bitter orange is mostly inedible, every part of the tree was used for food and fragrance. It was used in marmalade, to make orange flower water, and flavor liqueurs. It was used as an astringent, oral medicine, and dietary supplement. Neroli, a common perfume note still used today, is derived from the flowers of the bitter orange tree.

Perfume in the Middle Ages was far from the industry we know today. These fragranced liquids (distilled in water or alcohol) were not just worn, but consumed. Napoleon, Nordstrand noted, was a notorious perfume drinker and drenched himself in liters of cologne each month to absorb its medicinal and hygienic properties (the original eau de cologne, 4711 by Wilhelm Mülhens, can still be found today). While we tend to create a gendered distinction between perfume and cologne, Nordstrand pointed out that ‘cologne’ itself was a unisex style of citrus-based fragrances who earned their name from the city of Cologne, Germany where they were invented.

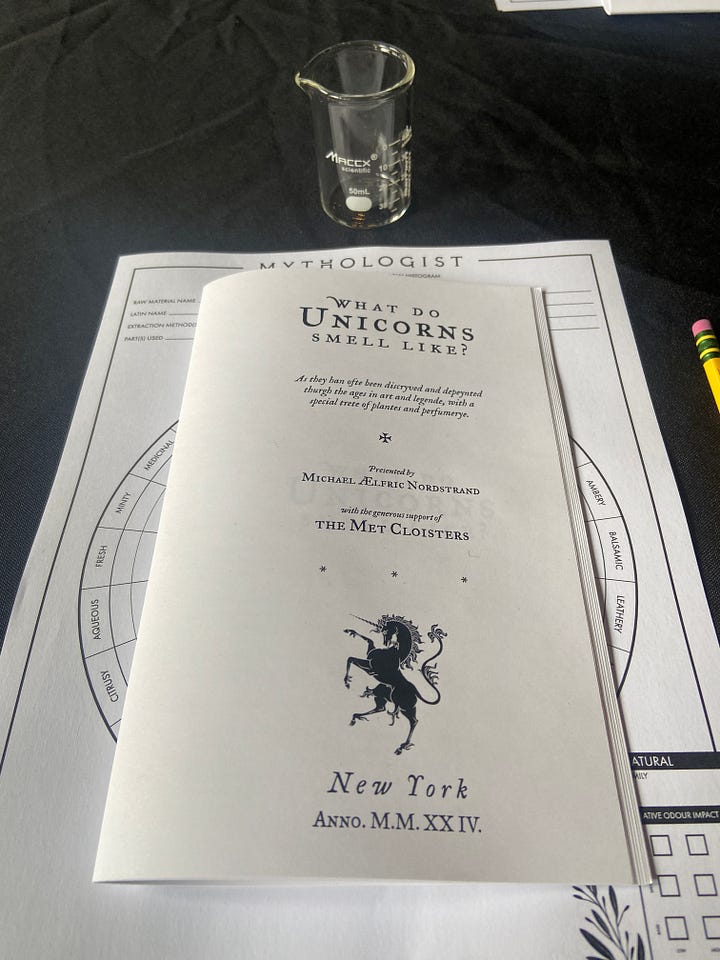

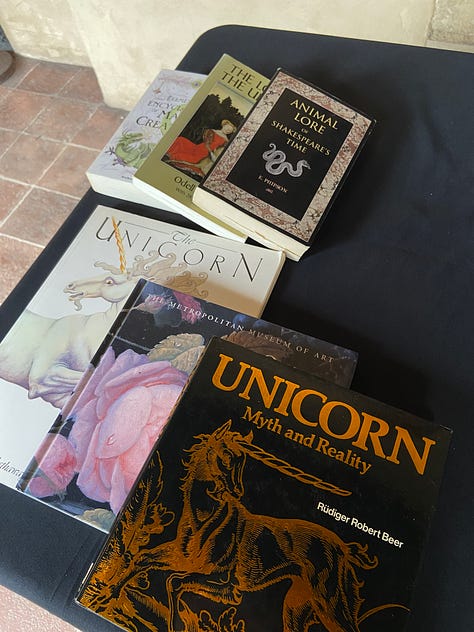

When we return back to the courtyard where the workshop is held, we are greeted with an array of tools: beakers, pipettes, gloves, formula charts, and a zine that broke down the different scent families, types of notes, and offered a few recipes of historic fragrances we could replicate or build off on (my personal favorite was Queen of Hungary's Water, one of Europe’s first alcohol-based perfumes invented in the 1300s, which included lavender and orange blossom).

As Nordstrand answered questions and explained some perfumery terminology, he passed around scent strips to give us a sampling of what kinds of scent materials we had at our disposal. We learned about top, heart, and base notes (usually determined by longevity) and about the lesser-known “agrestic” scent family made from plants that grow wild in the countryside and historically associated with Mediterranean botanicals. We got a crash course on how to measure out the amount of each raw material we wanted to use, best practices for using scent strips to determine how two odors might smell together, and how to avoid any accidental cross contamination as we blended our fragrances. A chemistry lesson among The Cloisters’ open air garden.

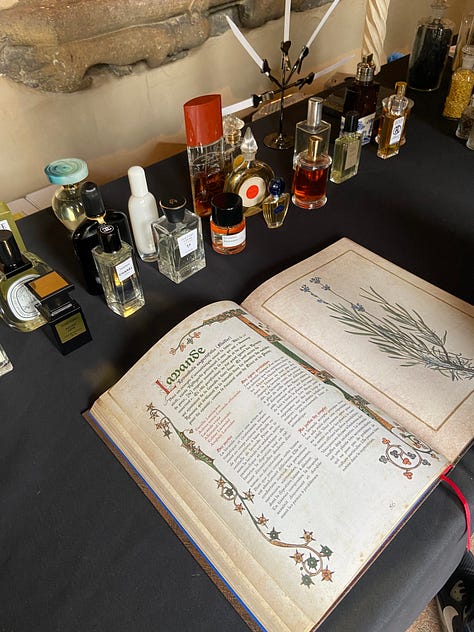

At the center of our workshop area sat a table with dozens of labeled glass bottles organized by fragrance family. You had florals, spices, woods, herbals, musks, and animalics. Many were distillations of the same plants we had seen in The Unicorn Tapestries with a few modern synthetics and base note blends to help us get started.

Off to the side sat a table with example perfumes we could smell to find inspiration, a mix of classics like YSL’s Black Opium and more contemporary and niche brands like D.S. & Durga’s Burning Barbershop and Loewe’s Agua. Even more evocative of a medieval apothecary were a bunch of glass bottles and vials full of the actual raw materials that are distilled into the little liquids found in our perfumes. There was saffron, a bunch of different resins, dried herbs and seeds. I even got to take a whiff of solid ambergris (a waxy material made from sperm whale intestines that’s been a coveted perfuming ingredient for centuries).

I went into this workshop with a half-baked idea of what I wanted to make. I kept thinking about this notion of a lamb waiting to be slaughtered, especially in the context of The Unicorn Tapestries which features the hunt and capture of the elusive mythic creature). I was interested not so much in the scent of the flowers blooming in these images, but the odor of animalic fear and the smell of confinement.

Because I was imagining a barn, I knew I wanted something that smelled like bright, fresh wood, but with a kind of vegetal, soil note underneath. Maybe something with a hint of hay to it. With the lamb, since I didn’t have too many powdery options at my disposal, I wanted to lean more into the sweetness of innocence, so something fruity or honey. In my initial brainstorm, I mapped out this rudimentary evolution from a soft, sweet opening to something more grassy in the middle, down into a woody base.

The process was ultimately a ton of trial and error. There was a lot of meticulous building up and diluting down of different concentrations. In between smelling my different options, I followed the advice of my instructor and smelled my skin and drank some water to reset my nose. I got to smell some familiar notes on their own that I had only ever experienced mixed in a perfume (like gooey osmanthus) and engaged with others that were totally new to me. Clary sage had that hay-like musk I was looking for. I didn’t expect to enjoy the delicate bloom of muguet (or lily-of-the-valley) and was caught off guard by the sweet, almond-like grassiness of coumarin. Ended up loving cypriol which bears a lot of similarities to papyrus and had a crisp, peppery green quality. Gagged a little at the pungent odor of civet (but also knew I wanted to incorporate it into my perfume somehow).

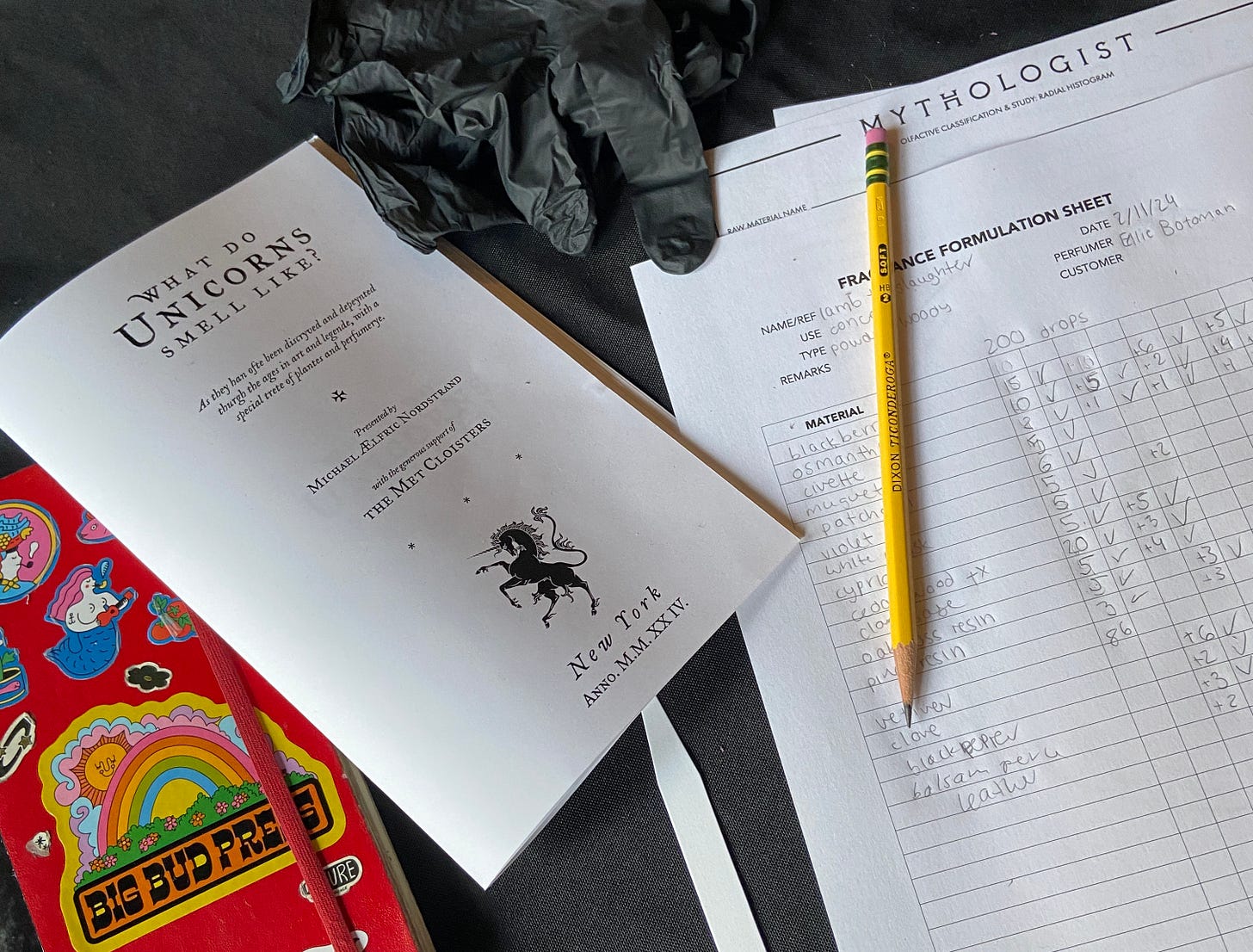

After almost 3 hours of carefully measuring, thoughtful smelling, and trying not to spill anything, I ended up with my first-ever perfume: Lamb To Slaughter.

In the end, I settled for top notes of blackberry, osmanthus, and violet. Blackberry reminded me of my childhood, osmanthus offered a sweet resinous depth, and a little bit of violet’s muted herbal, powdery softness. I went with heart notes of clary sage, white musk, black pepper and cypriol. White musk helped ease that transition to that woodier green, and I always love a little punch of pepper in my fragrances. At the base, I went with Texas cedarwood which gave me that fresh, wooden floor effect. Patchouli, oakmoss, pine resin, and balsam added a bit of soily depth. Leather helped me further define the perfume’s farm setting. hen I used the tiniest drops of civet to get that sour bite of animalic musk.

By the time I brought my beaker up to be bottled and labeled, I was already brainstorming what I would do differently next time I got access to a perfumer’s organ. Would I consider this perfume a success? Mostly. For my first try, I definitely fell victim to every novice perfumer’s tendency to “make mud,” in the words of Nordstrand, by blending together too many notes at once. The biggest challenge had definitely been trying to find a balance of concentration among all of these notes with such radically different intensities. I kept having to stop and smell my progress, trying to trust my nose to determine where I should be adding more to build up the fragrance. That being said, I was pleasantly surprised that I ultimately ended up with a final product that was somewhat wearable on the skin.

When the workshop ended, we were all swapping scent strips with our perfumes, seeing what we all made. Some were super sweet, others attempts at replicating one’s signature fragrance, and a few that took some creative liberties of their own. By the time I left The Cloisters and began to make my way downhill back to the train station, I was surprised that I hadn’t gone completely nose-blind yet. Although I tried to concentrate on my descent and not stumble down Fort Tryron’s steep trails, I found myself getting distracted by smells I hadn’t noticed before in the muted cold. The earthy rot of browned leaves, the wet humidity of the soil soggy with melted frost and rain. As I got closer to the city, I began to pick up on discreetly-smoked cigarettes and weed. The exhaust of cars and bus traffic. Half-finished coffees tossed into trash cans. The mouth-watering smoke emanating from a bustling halal food cart. Dust and graffiti paint and piss once I swiped into the subway station. The smells didn’t stop on the ride home. Yet, even as I teetered on sensory overload, I could feel myself get transported to that barn, that sense of fear, that sense of a doomed destiny amidst hay bales every time I brought the bottle up to my nose.

this is so, so great! sounds like a dream experience--thanks for letting me live through you :-)

Real interesting article! I have a large Osmansthus bush growing right next to my back door. Can smell it as I walk into my house. So, what did ambergris smell like??