Meet Jimmy Fay, Co-Founder of Close Friends Collective

A queer urban historian uses the walking tour to share NYC's hidden gay histories

Hello friends! This month, I’m finishing up my New City Critics fellowship with the Architectural League of New York’s publication Urban Omnibus and Urban Design Forum. I wanted to share a really great interview I got to do for one of our assignments. We were tasked to interview someone who is an expert of New York City, but not in the traditional sense. I immediately thought of Jimmy Fay, who I’ve known for ages and whose work as a poet and historian I’ve long been in awe of. As we’re in the midst of Pride Month, I knew I had to publish our discussion about their work with Close Friends Collective (who are currently booking their June and July tours of the Lower East Side and the East Village). Enjoy <3

Jimmy Fay joins our call the day after their first Lower East Side tour of the year. One of the six founding members of Close Friends Collective, Fay co-leads walking tours across the LES that center on the stories of lesser-known LGBTQ+ New Yorkers whose lives and legacies have shaped the city we know today. Fay, also a poet, actor, and playwright, first took an interest in interactive historical storytelling after working as a costumed educator at the Tenement Museum. Currently at Brown University pursuing an MFA in Theatre Arts & Performance Studies, Fay’s practice as a writer, researcher, and historic interpreter focuses on excavating queer pasts and imagining queer futures along New York City’s streets and sidewalks.

Close Friends Collective is composed of educators, artists, and historians with a deep passion for queer history and public education. Since the collective’s formation in 2021, the group’s pedagogical work has expanded into zines, events such as gay love letter readings, and, of course, more walking tours with new additions like the East Village and Green-Wood Cemetery. Close Friends Collective takes a communal, cooperative approach to public history, with members working collaboratively to research and uplift queer narratives of New York City often underrepresented and overlooked by traditional historic institutions. By bringing tour groups directly to these sites where events of queer protest, joy, community, violence, and discrimination unfolded, Close Friends Collective maps an alternative understanding of New York City through these queer historical figures and their communities—one that encompasses the diversity of their lived experiences with art, labor, policing, and social welfare.

During our conversation, Jimmy and I discuss their journey of becoming a queer historian of New York City’s Lower East Side and how these walking tours put Close Friends Collective’s mission of queer urban education into practice.

EB: When did you become interested in public history, specifically educating folks about New York City history and the people who’ve brought its neighborhoods to life?

JF: I started working in public history at the Tenement Museum as a part-time educator focusing on the history of the Lower East Side. I worked there in that capacity until I was laid off along with like 90-95% of the front of house staff in August 2020. When I and almost all of my colleagues were laid off, it was this emotionally difficult thing because we had gotten attached to the neighborhood and we knew so much about it. The job required this incredible depth of knowledge from us. I didn’t have any prior experience with public history. I started at the Tenement Museum in my capacity as an actor, actually. I was a costumed interpreter there, which was this bizarre job where I dressed up in garb from 1916 and played a 14-year-old immigrant from the Ottoman Empire—but that’s another story from another life.

EB: When did you decide to co-found Close Friends Collective?

JF: In 2021, a group of us who used to work at the Tenement Museum as well as our colleague Salonee Bhaman, who is an academic historian, were approached by a mutual friend that we all knew, Katie Vogel. She does public history stuff over at Henry Street Settlement, which is a social services organization on the Lower East Side. The staff at Henry Street wanted some kind of programming for Pride but they weren’t finding anything rooted in the history of the neighborhood. They commissioned us to write a walking tour that was supposed to be a one-off for Henry Street staff.

It’s something my colleague Nat Hill and I wanted to do for a really long time because we had, while working at the Tenement Museum, taken it upon ourselves to dig up a tremendous amount of queer history of the neighborhood and had been advocating for the museum to take that research and do something with it, programming-wise. During our tenure there, they never did. So, yeah, we were very frustrated by this lack of queer history in the neighborhood. Most of New York’s queer history tends to be concentrated in the West Village for understandable reasons. It’s where Stonewall and the Chelsea Piers are, stuff like that. But there’s queer history everywhere. The Lower East Side is this remarkable neighborhood that has had so many identities over the years and so many different identities at one time and continues to. We wanted to fold queer history into that because we saw a kind of lack.

EB: Why was the walking tour as a format so important to your practice?

JF: I really love it. In terms of why we do the walking tour, I think it’s nice to learn these stories standing in the place where they happened. I think that can be its own emotional experience where you’re communing with the past, but it’s also a nice way to be confronted with the realities of the present while we tell these stories. Yeah, there’s something about being out in the neighborhood among the people who actually live there that feels important to me. Like not being sequestered in an institution. It’s the kind of relationship we want to have with the past.

EB: Could you describe what the walking tour is like? Do you have any stops that feel always important to acknowledge when you go on these tours? I’m curious about how you structure it and where you go throughout the Lower East Side.

JF: It’s different every time. We have a repertoire of stops at our disposal and then, depending on the size of the group or the particular interests of the group or things like access needs, we’re able to tailor the tour to that specific iteration. We tend to give four, sometimes five, stops on a tour.

Henry Street itself is its own stop. Henry Street, as an institution, has this remarkable queer history because its founder Lillian Wald was herself queer. She was one of those incredibly ambitious and successful women who was married to her work and, you know, lived with all women. When your brain starts to catch on to little things that traditional historic interpretation will say about queer people without calling them queer, you start to see them everywhere, It’s like the “they were roommates” thing. That’s where our name comes from. Close Friends Collective is a cheeky nod to the erasure of queer people in the past. Anyway, Henry Street Settlement has this amazing queer history and continues to be a beacon of social services, mutual aid, and has, we think, this very queer ethos in the present.

Yesterday, we did a stop about a young person from 1856 called Charley, who was tried in this court case at Essex Market Courthouse for vagrancy. The New York Times published this article implying that the reason that they were arrested was because they were an “unfeminine freak” because they were assigned female at birth and were wearing male clothing. It’s this incredibly early instance of trans history there, and that stop dovetails with so many things in the present. It’s actually a bit frightening how relevant a lot of it has become.

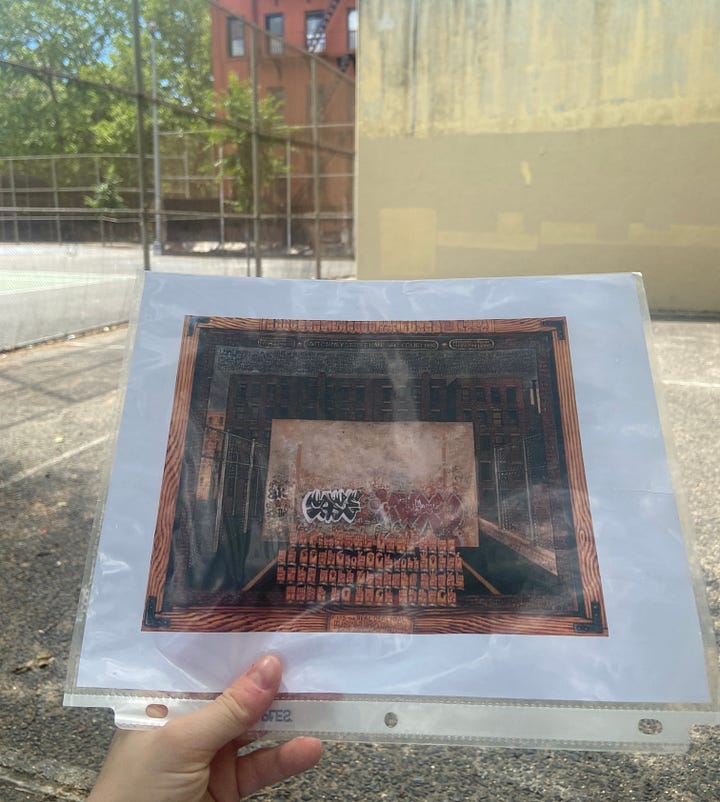

Then we talked about S.T.A.R. house. S.T.A.R. was an organization founded in 1970 by Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera. It stands for the Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries, and they had their headquarters for a time on 2nd Street. We talk about the artist Martin Wong and also a one-time lover, collaborator, and friend of his, Miguel Piñero who was one of the founders of Nuyorican Poets.

Bluestockings is our other institutional partner in the neighborhood. We also talk about the photographer Alvin Baltrop. We talk about political funerals during the AIDS crisis. There’s so many, but that’s the Lower East Side tour. We also have an East Village tour that just launched over the summer, so that’s a whole other one.

EB: There’s something beautiful in not just having one circuit that you do, but having it adapt to the kind of audience as well as also what you as historians are thinking about and researching, and making it timely. You can interchange these histories and tailor these tours in a way that, in a more traditional institutional format, you can’t or you’re more restricted.

I have a question about audience. What has your experience been like with the participants who come on these tours? Who is interested in them?

JF: The vast majority of the people who come on our tours are locals. Not exclusively. We do get tourists and that’s its own kind of fun experience, but most of the people we get on tours are from New York City. Many live on the Lower East Side, which is really cool. Part of the reason we reserve a section of free tickets for every tour is because we want people who actually live in the neighborhood to have access to the tour. It’s also a lot of people who are brand new to the city. Our tour has become this kind of homing device for newly arrived queers in New York to find each other. We get to see people making friends on the tours. Sometimes they’re flirting and it even gets a little cruise-y.

EB: That’s so fun. As someone who has worked in public history for a long time, I think those are my most favorite moments, where the people on the tour are talking to each other and also learning from each other and making friends, making community. It really demonstrates the power of Close Friends Collective bringing people together in this way.

JF: Yeah, I think it’s really nice to be able to tell these stories to a population who live in the neighborhood where it happened or the city where it happened and who have their own stakes. It’s a different goal that we have for this project than I think a lot of museums have.

EB: Is there any research you’re currently working on? A specific site or specific historical figures that you’re interested in including in the tour or expanding on in the tour?

JF: The stop on our tours that we’ve had the most breakthroughs with newly-discovered information has probably been Charley. That person we might today identify as trans, who was arrested in 1856. Their history intersects with this massive media matrix about trans people in the 19th century. Trans people, or people we would today call trans, were media sensations back in the 1800s all over the country in ways that are so surprising and also not surprising at all. Charley was part of this network of other trans masculine people who were famous in the newspapers for being continually arrested for being trans.

There was a person, whose birth name is Emma Snodgrass. They were arrested in Boston and I think again in New Hampshire. They were from New York, where their dad was a cop. So every time they got arrested, they were brought back to New York City and then they would abscond again to go live some trans life somewhere else. It seems like Charley and this person, Emma Snodgrass, were friends. So now we’re doing research about Emma Snodgrass.

Simultaneously, my colleague Daniel Walber and I are doing research at Green-Wood Cemetery for our Green-Wood tour, because that’s one of our other partners in the city. Daniel’s looking to see if any of the people we talk about from the Lower East Side have any connections to Green-Wood. We discovered this lot at Green-Wood that does have the Snodgrass name and then we went into further archival research and found that we do think this person who was born as Emma Snodgrass is probably buried there. We’re not 100% sure, but that’s an exciting update.

Also for our Green-Wood tour, I went to Washington D.C. to the Archives of American Art at the Smithsonian and did a bunch of research about this muralist called Violet Oakley who was pretty famous in Philadelphia in the early 20th century. She did all sorts of massive-scale commissioned art that, for her time, was a really big deal because she was a woman. She was one of those people who had this lifelong assistant and friend who lived with her, an artist called Edith Emerson. Historic interpretation of Violet Oakley’s life, even from in the copy that is on the Smithsonian website for her finding aid of her archives, describes Edith as her lifelong companion. Most historians have shied away from calling their relationship romantic but—because I’ve been doing this work for so long—I’m like, this person is gay. There’s no doubt in my mind. So when I was working at Green-Wood as an educator, I went to the Smithsonian to get concrete proof. I and CFC, as an organization, don’t believe in this idea of needing proof to call somebody in the past queer. But if these institutions want proof, I’m sure it exists. So I went to the archive and found this incredibly romantic and beautiful love letter between them. As far as I’ve seen, it has never been digitized or published. So, yeah, that’s the type of work we are currently invested in.

EB: How are you and CFC planning on expanding your work? Are there other parts of New York City whose queer history you’re interested in exploring? Or bringing these kinds of walking tours to those neighborhoods and finding community partners there?

JF: I think we definitely all have ambitions to reach other parts of the city. We are really interested in a Brooklyn tour. We’ve been researching different neighborhoods for where it might be possible. It’s harder in the other boroughs because the neighborhoods are less concentrated, so a walking tour can become more difficult geographically. But Park Slope has this really rich queer history, so does Brooklyn Heights. We’ve talked about that. We’ve talked about doing a Queens tour. With Queens, there’s so many different neighborhoods with such rich and interesting histories. Yeah, a Harlem would be amazing, too, but we have talked the most about a Brooklyn tour and a Queens tour.

We don’t want CFC to grow more quickly than we have the capacity for and we’re very happy with our present repertoire. It’s something all of us are so passionate about that we want to be able to sustain it for a long time. So we’re careful not to expand beyond our means at the moment. But those are some dreams that we have.

EB: Could you speak to what your experience has been like working collaboratively and in this collective mode to tell these stories of New York City Queer history? Community also feels really important in this context where you’re drawing these connections between past and present, but doing it in this communal way.

JF: Yeah, I keep pinching myself and being like, “Why is this working so well?” Because it’s hard with collectives, you know. It’s not like our work is without conflict, but I think what helps is that all of us are genuinely really good friends. When we do get together, we certainly spend some time talking about the Collective and we have agenda items and everything, but we also just vibe and hang out. We all love each other and I think, crucially, we all respect each other.

EB: What does it mean for you, personally, to do this work of queer urban history? Especially in this time when LGBTQ+ rights are being so threatened and these histories are being erased. Like when the T is getting dropped from government archives, you know, and stuff like that. What has this work has signified for you as a historian and also as a queer person?

JF: I was one of those children obsessed with history, but I never encountered anything resembling queer history. If we learned about queer history, I’m sure it was a paragraph about Stonewall. And I’m sure I did not see myself—a tiny closeted dyke from rural Arizona—in that story at all.

I hope that what these stories do for people is plant this idea that queer people have always existed, and all kinds of queer people have always existed. I am particularly moved by the story of Charley at the moment because seeing such an explicit example of trans history from as early as the mid-19th century is, for me, proof positive that transness has also always existed. Even at a time when people didn’t have language for it.

At a time when the government and so many empowered and emboldened people hold this line that being trans is some kind of new language that has this agenda and is seeking to infect the innocence of American body politic. It’s just patently not true. Any queer or trans person could tell you that is not true. So that’s the work of history, right? Let me go back and find specific examples where that’s true and put it in your face and be like “Look, how can you tell me that isn’t real?” How can you tell me that we didn’t exist?” I think that’s the emotional connection I feel to it, especially right now.

EB: How has the work of CFC changed how you experience and see New York?

JF: I remember working at the Tenement Museum and giving a tour to this group of school kids who, I think, were in the fourth grade. The Tenement Museum is partly housed in this old crumbling tenement, which is this amazing and fascinating and gorgeous building. But sometimes it would really freak kids out. This one kid was really losing it and he kept being like, “Did somebody die here?” As a historian, I wasn’t going to say no because obviously tons of people lived there. Certainly, people died there. So I didn’t know what to say. But his teacher was like, of course, somebody died here but somebody died everywhere in New York. I watched these kids’ eyes go big with this revelation. I think that’s analogous to how I see queer history now. It’s like, somebody gay was here. Everywhere. On every corner. Even in the neighborhoods that weren’t thought of as these big gay hubs, there were gay people everywhere.

EB: Yeah, it’s like one of those moments when you’re meeting up with your friends on the street corner and you’re thinking about other queer people who also probably met their friends on the same street corner. There’s something really poetic about that.

I think what it also does for me, emotionally, is that I see my own ancestry everywhere. It’s nice to be able to connect with these historical figures, in the way that queer people are always making their own families. I see something of myself in the story of somebody like Charley and any of the other queer or trans people who have lived in the city that I call home. When I’m hanging out with my t-boy friends, I’m part of a legacy. We become part of this lineage.

Brilliant brilliant interview!!! Thank you so much Ellie!!!