Notes From A Heatwave

Air conditioning isn't going to save our warming cities

“Angels are unthinkable / in hot weather,” - Monica Youn, ‘A Parking Lot in West Houston’

The story goes like this: the Sackett and Wilhelms Lithography & Printing Company was struggling to keep the humidity levels in their production rooms low. Their paper was warping from all the moisture in the air and the inks weren’t drying properly. Engineer Willis Carrier was hired to find a solution. The result was a machine—the Apparatus for Treating Air—that pumped air across metal coils cooled with ammonia that drew moisture from the air. Not only were these spaces much drier but, in the hot summer months of 1902, significantly cooler than the rest of the building. It’s said that the room where Carrier installed his new invention became the preferred lunch spot for Printing Company employees.

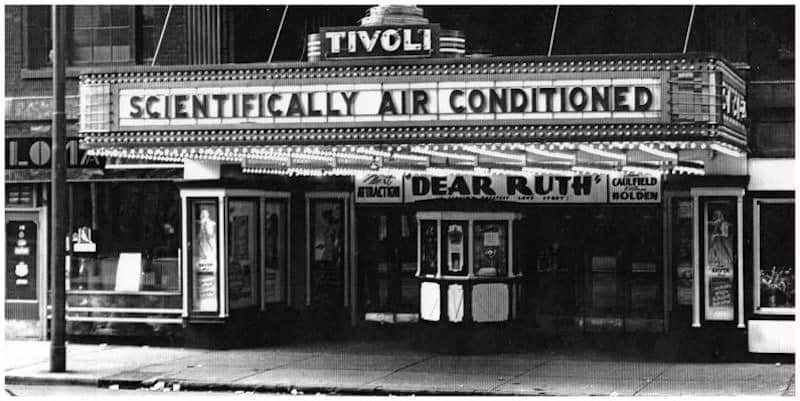

Yet, air conditioning didn’t stay inside factory buildings for very long. Movie theater owners became one of Carrier’s biggest customers as once sweaty, crowded theaters became places where movie-goers could find relief from the sweltering summer sun. Eventually, smaller air conditioning systems would make their way into the homes of the wealthy, although it wasn’t until the 1940s that the window-sized units we know today became cheaper to produce and more widely-accessible, bringing mechanically-chilled air to more homes and buildings across the country. Now approximately 10% of households have no air conditioning whatsoever.

As I write this, there’s a patchwork of heatwaves blooming across the country. Regions known more for their brutal winters are now sweltering under record-breaking temperatures. Parts of the Pacific Northwest are expected to exceed 100℉ (38℃). Further south, the drying heat of California has sparked yet another brutal wildfire season, sending the Oak Fire ripping through Yosemite National Park and Mariposa County. In the Sun Belt, Texas’s power grid was once again threatened by rolling blackouts, this time due to surges in electricity demand due to high temperatures. I spent this past weekend, like many in the Northeast, practically catatonic in bed with my fans and air conditioning blasting and a blanket covering the window, occasionally moving from the small sauna of my living room to a periodic cold shower like a sweat-soaked slug.

In Europe and Asia, things haven’t been better. In fact, they’ve been much worse. In China, temperatures are expected to reach almost 104℉ (40℃) this upcoming weekend. Parts of India and Pakistan—regions that climate scientists expect to be unlivable by the end of the century—have been getting hit with disruptive heatwave after heatwave since the start of summer. In Spain and Portugal, heat-related deaths were not in the dozens or hundreds, but in the thousands. Wildfires in France, Spain, Greece, and more have devastated acres of land and led to evacuations. In the United Kingdom, high temperatures shut down London, melted streets and airport runways, and exposed serious flaws in local infrastructure. The city of Seville has launched a ranking and naming system for heatwaves, with Category 3 heatwave Zoe as its first.

The knee-jerk reaction for heatwaves like these is always the same: installing more air conditioning everywhere whether that be through purchasing window units or installing central AC into new construction or remodeling pre-existing buildings. During the heatwaves in Europe, I kept reading, hearing, and seeing videos about the ‘culture shock’ of the region’s limited use of air conditioning, that many who moved there from the States hadn’t expected to move into places that didn’t have any AC. The reality is that the US is an outlier in air conditioning use compared to the rest of the world. A 2016 study found that 328 million Americans consumed more energy for cooling than all of the people living in Africa, Latin America, the Middle East, and Asia (not including China) combined. A 2018 report from the International Energy Agency noted that only 10% of homes in Europe are air conditioned. Of course as people experience these extreme weather events—especially in places that have been built to keep warmth in not out—mechanically-cooled air is incredibly appealing and can even be life-saving. But is this really our only option as our summers get hotter?

The negative environmental impact of air conditioners on our cities has been studied for years now. Older models of air conditioners released harmful greenhouse gasses in the form of CFCs up until the 1980s, and even newer units still rely on polluting, heat-trapping chemical refrigerants. Stan Cox, the author of the book Losing Our Cool, noted in an interview that the emissions from air conditioning use in the United States is estimated to be about 500 billion tons of CO2 per year, greater than the country’s construction industry. While they offer short-term relief, air conditioners aren’t an efficient way to keep us cool. Along with pollution, emissions, and expelling hot air, high use of air conditioners can put a strain on power grids and dramatically increase our energy consumption. Take, for instance, the Sun Belt where cities like Phoenix, Scottsdale, Austin, San Antonio sweeping all the way across the south to Florida have seen huge population surges coincide with record-breaking temperatures and high energy consumption. One recent calculation put America’s electricity consumption for cooling alone at 616 terawatt hours (for comparison, China came in at 450 TWh and the rest of the world at 334 TWh). As Europe recovers now from this extreme heat, it’s clear that pushing for more air conditioning will be an expensive investment and overhaul of countries’ infrastructure, something not made easier by high energy prices exacerbated by the war in Ukraine.

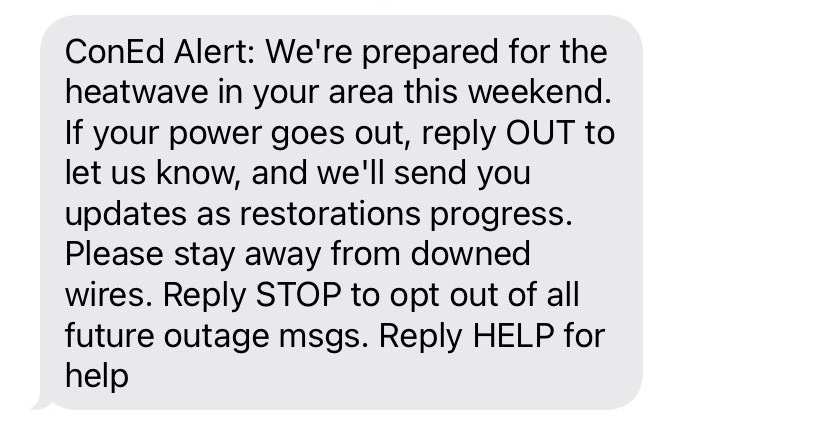

As someone who grew up in the air-conditioned comforts of Florida, then moved to New York where I experience record-breaking heat year after year, I’ve been thinking a lot about how we should (but aren’t) redesigning our homes and our cities to meet the demands of a warming world and keep our communities safe and resilient. Like many other NYC residents, I was bombarded by text messages from Con Ed in the days leading up to the heatwave, a steady stream of reassurances that they would do their best to avoid blackouts as people crank up their cooling systems. Along with these messages came all kinds of ‘tips’ for what we, as consumers, could do to help: turning off units or raising thermostats to consume less energy, only running other appliances at cooler times in the day, and more obvious suggestions like keeping curtains drawn and windows closed. Advice like this (which I also saw echoed in Texas) doesn’t make a whole lot of sense when the power stays on in office buildings whether or not they’re occupied, or you see places like Times Square stay lit up during the day. The reality is that low income communities are sacrificed first in the name of ‘saving energy’ during heatwaves and see their power restored last. The problem of these dangerous tactics from utility companies, especially when ‘just buy an AC’ is touted as the go-to cooling strategy for our cities, isn’t something that gets solved by one person turning their thermostat up to 80℉ during a heatwave.

Let’s start with what we’ve lost in the age of air conditioning: regionally-specific (also known as vernacular) architecture. In parts of the country where long, hot summers are the norm, homes were oftentimes built with elements like porches to help keep residents cool and designed with layouts that allowed breezes to circulate throughout the structure. Construction materials like adobe were commonly used in especially hot desert climates because of its ability to manage heat. The advent of cooling systems meant that buildings no longer needed to be designed with the particular climate of an area in mind. As construction boomed, structural designs became standardized in order to spur the mass production of homes and the paved expansion of urban areas. An AC system was a cheaper and faster alternative to spending time on vernacular design elements or materials, and installing these meant that high-rise buildings could become more densely packed with office space and apartments since you no longer needed things like extra windows to ventilate this temperature-controlled environment. Now we’re stuck with buildings in hot areas that aren’t designed to stay cool, reliant instead on air conditioning systems that are entirely at the mercy of local power grids. As countries and regions confront the reality that they’ll need to adapt to rapidly warming weather, these cooling elements of vernacular architecture that were once deemed superfluous should be revisited.

Now, as the demand for buildings adapted to hotter climates grows, architects are beginning to once again incorporate passive cooling designs into their structures, taking inspiration from human history and the natural world alike. Several firms in Senegal are experimenting with mud and adobe as energy-efficient alternatives to concrete and its massive carbon footprint. For their design for the Pearl Academy of Fashion in Jaipur, Morphogenesis took inspiration from “baolis” (wells) and “jaalis” (perforated screens) found in old forts and palaces across India to create a building that can stay cool thanks to an underground pool of water and shade-blocking facade. For centuries, Iran’s desert cities have kept cool through windcatchers. These towers bring air flows into buildings’ interiors (sometimes in tandem with water reservoirs known as ab anbars) without the need for electricity-based cooling systems. The Bauhaus-inspired University of Ife in Nigeria incorporates modernist ideas into vernacular design, while the Laayoune Technology School in Safi, Morocco incorporated several cooling strategies into its layout like double-skin facades, covered walkways, and brise soleil shading. In more tropical climates, buildings like the Stepping Park House in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam show how greenery like plants and trees can support open, ventilated structures with their shading and emission-absorbing effects.

I’m always so fascinated by biomimetic architecture, and I’ve especially loved learning about the ecological elements that shaped the design of the Eastgate Centre in Harare, Zimbabwe. This massive office building and shopping center, built in 1996, was designed in direct opposition to the traditional ‘big glass blocks’ we associate with our modern cities. Rather than deal with a building that can be expensive to maintain and keep cool with fossil fuel-powered central air conditioning system, architect Mike Pearce created a ventilation system that uses fans in the building’s basement to push hot air up and out of the building through a series of ducts that keep internal temperatures regulated and an external facade with vegetation on its sides that help absorb the heat of sunlight. The whole building’s energy efficient design takes inspiration from African termite mounds. These mounds help protect the termites from extreme heat through an elaborate system of heating and cooling ducts that circulate down, through, and out of the partially underground structure.

We know for a fact that if we want to have greener communities, we need to build our cities with density in mind. Passive cooling designs like that of the Eastgate Centre show us that air conditioning isn’t the only way to keep us cool in highly-populated urban areas and, if we’re going to wean ourselves off fossil fuels and save energy, we need to find more efficient ways and incorporate them both in new buildings and our pre-existing infrastructure.

In this conversation about keeping our cities and communities cool, I would be remiss if I didn’t talk about trees. As cities grew and began paving over land to create streets, sidewalks, and parking lots and began building with materials that reflect heat (think: glass and the light surface of concrete), displacing shady trees and greenery along the way, these design choices led to the creation of the “urban heat island effect” wherein spaces have an increased intensity of heat, which in turn leads to increased energy consumption inside buildings, increases emissions, and puts people at greater risk of heat-related illnesses since there’s no cover to protect them from the sun. The presence (or lack of) trees in city neighborhoods continues to be a damning indicator of environmental racism. Study after study after study have shown the way low income communities of color are segregated based on access to green urban infrastructure like trees planted along streets, community gardens, public parks, leading to higher temperatures and health impacts from pollution in those neighborhoods. Conservation group American Forests has even launched a Tree Equity Score to further quantify these gaps among urban communities.

Honestly, though, you don’t need scientific research to understand these thermal disparities. Spend enough time walking around your city or traveling from one neighborhood to another and you’ll be able to feel the differences in heat. In New York City, this can sometimes happen on a street by street basis. It’s not uncommon to see lots of tree cover on residential streets that have high rates of homeownership, while streets that have mostly rental properties or are in lower income, more industrial neighborhoods might be lucky to have a single tree or two. Recently, I had the misfortune of walking around the barren streets of Lower Manhattan while running an errand. I kept ending up in these stretches of SoHo and Tribeca that had no shady tree cover to speak of, just blindingly-bright sun bouncing off the concrete sidewalk and luxury all-glass buildings that wore me out despite all of the water I drank and sunscreen I had on. My only option was to duck into one of the many air-conditioned high end stores or overpriced restaurants that populate these areas where I’d probably have to shell out $5-$6 for an iced drink just to be able to stay in the space. Occasionally, I’d walk past a building and get hit with hot air getting expelled from its cooling system, which didn’t make the walk any easier. I haven’t been able to shake just how awful this kind of poor urban design was to see and experience, especially since New York City’s humid climate is now considered to be subtropical. For all of the annual panics about the potential power grid failures and high energy demand during heatwaves, it’s clear that a policy decision as simple as planting more trees on barren city streets would make significant improvements to quality of life and reduce the need to blast our ACs.

Unlike other destructive weather events like floods, hurricanes, or tornadoes, we can’t always see the toll extreme heat takes on our communities—although now many of us are starting to feel it with greater intensity each year. Even though many of us are now spending this summer seeking out shade, we’re not in the dark about expected rises in global temperatures. Many cities are now having to confront hotter and hotter seasons, even if their climate was once mild, and that means unprecedented changes in urban design and infrastructure if we want to keep these spaces safe and habitable. After living through a July marked by deadly heatwaves and seeing the rippling effects of wildfires and droughts around the world, it’s clear that we need to rethink the way we keep our buildings and our cities as a whole cool.

The rise of air conditioning offered the unprecedented luxury of climate-controlled buildings, but it also led to the phasing out of architectural styles and design elements that once helped homes and workplaces cool without AC. While some cities like New York or Chicago have greater degrees of walkability, the prevalence of cars meant less incentive to invest in green spaces and trees (especially when people are just parking and walking straight into an artificially-cooled interior). High heat and access to cooling is also very much a socioeconomic and racial justice issue as neighborhoods have to bear the burden of blackouts, lack of vegetation, and high energy costs during these extreme weather events. When I see designs proposed by architects that bring passive cooling back into our structures, whether that be through reviving ancient or historical building techniques or taking inspiration from nature, it’s a reminder that air conditioning and all of its energy-exhausting emissions isn’t the only solution to our warming planet. In fact, these kinds of designs and strategies like planting vegetative shade can help open up our enclosed spaces and bridge the indoor/outdoor divide. Other effective strategies like planting trees to build temperature-lowering cover also helps us reconnect with and reimagine our relationship to the climate of our communities, enabling us to adapt to current climate impacts and be more resilient in the years to come. As easy and lovely as our mechanized cooling comforts can be, it’s time to face the heat.