On World-Making

“How do people resist in the dark ages? What keeps us going, ultimately, is our love for each other, and our refusal to bow our heads, to accept the verdict, however all-powerful it seems.”

Back in 2017, fiction writer Lincoln Michel described world-building as “the most overrated and overused concept in fiction.” I can’t blame him for feeling that way. World-building has become a buzzword, thrown around in contexts completely disassociated from its original meaning until it is nothing but an empty signifier gesturing vaguely to minor acts of setting design. In a time when every corporate business hungers for immersive experiences and brand storytelling, world-building has become touted as an innovative marketing strategy with little regard for its history as a complex, challenging tool in the arsenal of artists, writers, and visionaries.

Traditionally associated with literary craft—particularly science fiction and fantasy genres—this concept has permeated into other media like TV, film, video games, and even theme park experiences. World-building demands holistic planning and realization. Michel notes that it “expects the author to have ‘rules’ that are ‘logically’ followed to their conclusions.” This means developing specific technologies, ecologies, languages, human and non-human communities, historic traditions, and religious systems. The inclusion of little details and aesthetic minutes can often make or break the realization of a constructed world. Some are obvious (like inventing your own word for ‘champagne’ since France shouldn’t exist in your fantastical realm), while others might be more subtle (like inventing manners of speaking and dressing oneself within the confines of this setting). By establishing these spatiotemporal, political, cultural, and psychological parameters, you create a setting that scaffolds the narrative of your story, gives something for characters to navigate through and react to and for the reader or viewer or consumer to reflect on their own realities.

When it comes to the world-building of science fiction and fantasy stories, we tend to assume that there’s an element of escapism built into it. Even if the setting isn’t exactly a peaceful break from reality (think: post-apocalyptic wastelands and war-torn kingdoms), really good world-building sucks you into an alternative world and gets you so immersed that you can pause thinking about your own life. But I find that’s rarely the case. The most effective world-building I’ve encountered doesn’t just handle little details with great thoughtfulness and care for its story; it actively reminds me to look at what’s happening in my own world, to draw parallels and make connections to these fantastical settings and present-day struggles and past histories.

Science fiction and fantasy have always been fundamentally political genres, serving as opportunities to explore ideologies and enact thought experiments with rearrangements and inventions of new social, economic, spiritual, and political systems. Far from neutral genres, SF&F grew out of and in response to histories of colonialism and imperialism, often wielded as a tool for propaganda. Yet world-building within these genres also gives us an opportunity to dismantle the systems that be, to find resistance through imagination, to incite social critique and critical self-reflection. As Ursula K. Le Guin once mused, “We live in capitalism, its power seems inescapable—but then, so did the divine right of kings…Resistance and change often begin in art. Very often in our art, the art of words.”

World-building has been on my mind lately. How can it not be with the ongoing genocide in Gaza and the political chaos here in the States? Amidst horrific reports that rebuilding Gaza will take decades and billions of dollars, the devastation of entire families and their histories wiped out in relentless bombing and sniping, testimonies of navigating an apartheid state not designed for you (something I witnessed firsthand navigating checkpoints to enter the West Bank and Occupied East Jerusalem in 2016), I’ve been thinking about the work of Palestinian science fiction writers.

Back in 2019, the short story collection Palestine + 100 invited authors to imagine what Palestine would look like in the year 2048 (100 years after the Nakba), while Reworlding Ramallah curated stories created during science fiction writing workshops at Disarming Design. The forthcoming speculative fiction anthology, Thyme Travellers, also seeks to bring together voices from across the Palestinian diaspora, infusing futuristic worlds and alternate realities with Palestinian folklore and history.

The writing of queer Palestinian performance artist Fargo Tbakhi, in particular, has taken on a profound new poignancy for me over these past 10 months. I recently revisited Tbakhi’s story “12 Words Interrupted By The Drone” (published in 2020) and, as I read about the military machine encountering a young boy on its journeys of destruction, I thought about the “zanana” or the terrorizing buzz of Israeli drones that have haunted the children of Gaza since childhood. In a poem for Strange Horizons’ 2021 Palestine Special Issue, Tbakhi declares: “PALESTINE IS A DREAM OF THE FUTURE! / FUTURE IS A PALESTINE OF THE DREAMING!” Will we join him in this radical act of resistance through imagination?

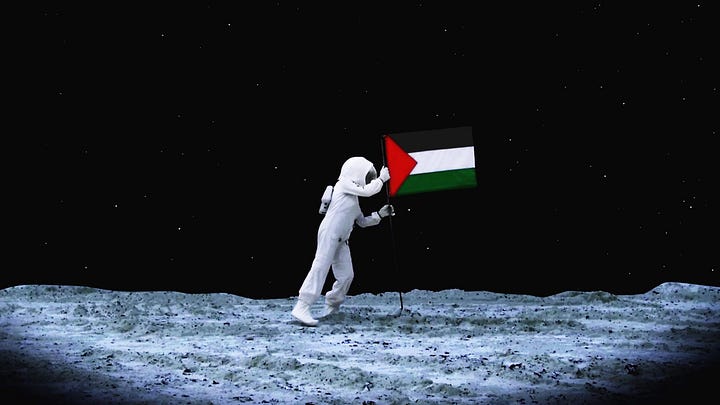

Beyond the page, I’ve been reflecting on Larissa Sansour’s speculative creative practice. Sansour uses the storytelling tools of science fiction to grapple with Palestinian histories of displacement and erasure, while also inviting us to dream of reunification and sovereignty through the creation of alternative homelands. I think about A Space Exodus (2009) and how it imagines the first Palestinian in space through the aesthetics of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, taking a politically playful look at space exploration as both a symbol of human progress and a problematic neocolonial venture. Archeology in Absentia (2016) and Revisionist Production Line (2016) take up archeology as a tool and victim of warfare while also exploring its potential influences on national identity formation. Nation State (2012) offers a subversive solution to the ongoing resistance to Palestinian statehood: a single skyscraper that houses the world’s entire Palestinian community. Sansour shows us that ‘home’ isn’t just a past place or a present feeling. It is a powerful call to envision futures of belonging, to move forward as well as to return.

If world-building makes us roll our eyes, evokes images of destruction and domination, or restricts us to strict rules of regimented construction, then I propose ‘world-making’ as a way to counter this feeling of creative confinement. World-making is fluid, dynamic, and responsive to the urgency of this current political moment. It weaves, knots, entangles. World-making invites us to bind our histories and our dreams to each other, to bridge distances in a time when we have become more divided than ever.

Like many students across the country, my spring semester was shaped by the presence of campus solidarity encampments. Even in the face of angry donors, threats and acts of expulsion, withheld degrees, attacks by fellow students, and brutality inflicted by administrators and police officers alike, students from the youngest of freshman to the most senior of faculty stood their ground, demanding disclosure and divestment from the U.S. military and from companies and individuals who have been financially, culturally, and politically complicit in the ongoing occupation of Palestine and the current scholasticide in Gaza.

It was a beautiful thing to witness. These student-led encampments offered us a glimpse into a possible, improved future of higher education. Alternative forms of educational communities rose up in opposition to decades of corporatized bureaucracy and the whims of benefactors. Students and faculty pooled resources together to buy and distribute food, bail out their peers, and provide mutual aid to the campus’s most vulnerable members. There were hours for religious prayer services and free libraries, teach-ins, readings, and film screenings all with an open invitation for everyone to join, share skills, or to simply come and learn.

As Samuel Caitlin notes, “the future of the nation itself is taken to be at stake in what happens ‘on campus.’” While others saw these solidarity encampments as a threat to the status quo, protestors took this opportunity to draw connections between the struggles in Palestine and injustices faced here. Discussions about Israel’s illegal military occupation, apartheid, human rights abuses, and flouting of international law are interwoven with reflections on America’s longstanding racial segregation, police brutality, and contemporary legacies of colonialism and military imperialism. This fight for liberation has and always will be a collective one. Students were no longer theoretically debating what a more just and equitable future might look like on their campuses and beyond. They were working together to make that better world a reality.

Palestinian SF editors Nadia Shammas and Summer Farah tell us that “the ability to imagine another world is vital to producing a better future. The ability to imagine another world is vital to processing the pains of this one.” World-making is not just about crafting something better and new, but a call to return, to reflect, to reckon with the past in order to understand our present and explore our future.

As I was preparing this essay, I realized we had arrived at July 20th, 2024—the date that opens Octavia Butler’s 1993 apocalyptic novel Parable of the Sower. Unsurprisingly, people have a renewed interest in the book’s seemingly prophetic depictions of America’s sociopolitical collapse. Can you blame them? We’ve been witnessing a tremendous unmaking in our country: the dismantling of legal protections and of our basic human rights, the rise of fascist racist and religious extremism and the oppression that comes with it, attempts to impede democratic processes through suppression and corruption. But we forget the opening words of Butler’s fictional Earthseed ideology: “All that you touch / You Change. / All that you Change / Changes you.” Her speculative novel signals warnings, yes, but not that our doomed fate is sealed. It’s okay to feel despair about the state of our society, but world-making reminds us that what we have now is not the be all and end all. There is always more we can do to fight back and take care of each other.

In a 2022 interview, just two months before his death, writer Mike Davis posed a question and an answer: “How do people resist in the dark ages? What keeps us going, ultimately, is our love for each other, and our refusal to bow our heads, to accept the verdict, however all-powerful it seems. It’s what ordinary people have to do. You have to love each other. You have to defend each other. You have to fight.” In world-making, that form of resistance through love can take on the form of creating something new, stronger and more beautiful, and sharing with others. We have the power to decide collectively that we don’t accept this situation as it is. We deserve something better.

So go out there and make worlds. Make them powerful and beautiful and welcome to all. Make them just and kind and peaceful. Make worlds with love, fear, and compassion. Use world-making to resist through radical acts of imagination by thinking, critiquing, doing, and dreaming together.