We lost David Lynch nearly a month ago—that mighty force in America cinema whose eye for the dreamy and the unnerving has influenced our popular culture for decades and will continue to for generations to come. Amid reading the heartfelt tributes to his love of coffee, cigarettes, candy, and transcendental meditation, I’ve been reflecting on what his oeuvre has meant to me. How his vision of Surrealist Americana shaped the way I think about style, scenery, symbolism, and storytelling. I keep coming back to those red manicures of his most complicated women.

I first noticed these pops of color on the fingertips of Twin Peaks’ Shelly Johnson. Dropping out of high school to work at the Double R Diner after marrying abusive trucker Leo Johnson, Shelly has to live a very different life from the town’s other young girls (who are often seen sporting bare nails or the palest of pinks). She’s forced to grow up faster than the rest of them, more of an ‘adult,’ and expected to conform to Leo’s expectations as the attractive, young housewife. Yet, there’s also a rebelliousness to her, a willingness to fight for her own survival and the life she truly desires.

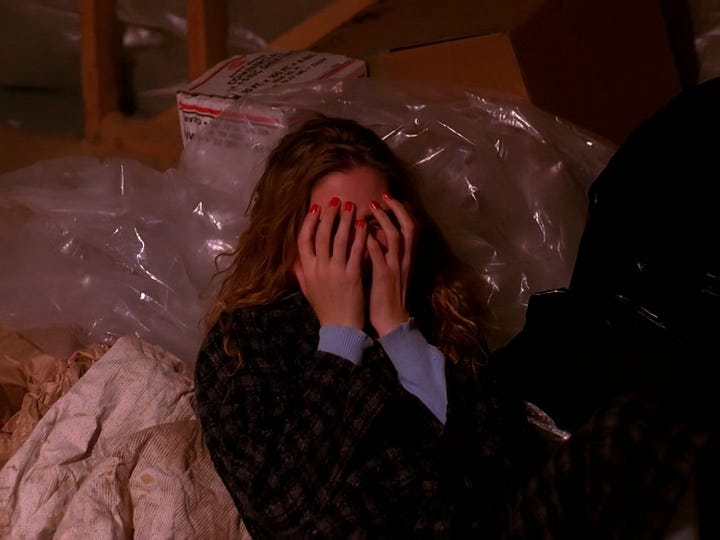

Red nails appear again and again in the larger Twin Peaks universe. You have the chipped cherry polish of Teresa Banks, a teenage drifter and sex worker whose demise at the hands of BOB/Leland Palmer we see in the 1992 prequel Fire Walk With Me. In Twin Peaks: The Return, we see middle-aged Audrey Horne caught in a kind of purgatory, all dressed up and nowhere to go trying to convince her husband to join her at The Roadhouse. After performing one final dance, it’s revealed that Audrey has been in a mental institution this entire time after her beauty salon business closed down. For these women, red reflects their attempts to assert their independence and autonomy, but also their inescapable confinement within brutal patriarchy.

Lynch populates his movies with the color red—shades of lipstick, high heels, the velvet curtains of the Black Lodge, roses, and blood. It’s a hue that symbolizes moral ambiguity, dichotomies of purity and violence, expressions of sexuality. Red represents Lynch’s fascination with 1950s-esque small town America just as much as it does the glamour of Hollywood, where the lines between fantasy and reality blur into great beauty and tremendous terror. Painted nails are fairly mundane, but their presence in Lynch’s films imbues them with this sense of the macabre as these troubled women caught up in the darkest underbellies of American life.

Perhaps the most obvious example is Rita from the 2001 neo-noir Mulholland Drive. A survivor of a car crash that left her with amnesia, Rita names herself after the iconic Rita Hayworth (known for popularizing the crimson manicure in the 1940s) and has the red nails and lipstick to match. This film wrestles with the rot at the heart of the film industry, with characters who cling to the romantic allure of Hollywood and its possibilities of self-invention. Rita/Camilla Rhodes embodies these anxieties. She is the ideal sexual fantasy of the damsel-in-distress, a vulnerable feminine object ripe for misogynistic consumption by ogling directors and film executives. Yet Rita/Camilla’s red manicure disappears when we emerge from Diane Selwyn/Betty’s apparent post-breakup fantasy. She ultimately represents Diane’s failure to achieve the American dream as a movie star. She wants to be the lead of the story, but fails to ‘get the girl’ in the end as Rita/Camilla takes her film role and a new lover. Rita’s red manicure symbolizes a kind of classic Hollywood beauty that remains out of reach for the women caught up in this monstrous system of jealousy and self-destruction.

Of course, there’s Dorothy Vallens from the 1986 classic, Blue Velvet. She is simultaneously dangerous and in danger, a modern-day femme fatale whom Lynch reminds us is also a victim of sexual violence, an abducted mother and wife forced to perform the part of a singing seductress to evil men. Blue Velvet concerns itself with the undercurrents of toxic masculinity and gendered violence within suburbia, especially seen through Jeffrey’s entanglement with Dorothy and his drive to save her from this sadomasochistic abuse. Dorothy’s red nails are a warning about this illusion of safety, the abuse and misogyny that manifests under this facade of seductive beauty. She appears as a fantasy, but is really living a nightmare.

In the 1990 romantic comedy crime thriller Wild at Heart, Lula Pace Fortune’s red nails have a punk-ish edge. On the run with her Elvis-obsessed boyfriend Sailor, Lula’s Southern drawl and bouncy blonde pin-up model curls and cherry manicure embody a quintessentially American beauty. So much so that Barry Gifford, author of the book that Lynch adapted, described her iconic style as akin to Marilyn Monroe. It’s this very youthfulness that sparks the jealousy of her mother. Fortune hardly conforms to proper gender norms a la old Hollywood. She’s eager to rebel. She loves speed metal. She’s boldly sexual, loving, and flirtatious. She’s earnestly passionate, emotional with a naive optimism that makes her a ray of light capable of surviving this dangerous world.

Red has long been a go-to manicure color for centuries. We know that members of Chinese royalty in 3000 BC used vegetable dyes to stain their nails red. The highest-ranking women in Ancient Egyptian society also colored their finger tips red as a show of status. In America, red nail polish first became popularized in the late 1920s and the early 1930s after catching on among European socialites. With the invention of nail enamels during the Great Depression, early shades like Revlon’s Cherries in the Snow and Scarlet Slipper allowed women to imitate the manicures they saw on famous actresses from World War II onwards. This particular nail polish shade has come to be associated with sex workers, celebrities, girlbosses, rebels, and housewives.

While the trend fell out of style in the 1970s, red nail polish never truly went away. It remains a popular choice at nail salons for those seeking something bold and beautiful. We still associate it with sexuality, luxury, and confidence. It’s the color you wear when you want to make a statement, express your ferocity, or seek a certain kind of American nostalgia. A renewed fascination with this color led to the viral “Red-Nails Theory,” where a TikToker speculated that men are attracted to women with red polish because it reminds them of their mother (a chilling parallel to the villainous Frank Booth’s repeated calls of ‘Mommy!’ in Blue Velvet). While the theory itself might be some Freudian bullshit, it speaks to the color’s contradictory symbolism and its complicated associations with femininity. At times, red nails can evoke a campy, countercultural subversiveness; other times we associate it with the national decline into fascist conservatism and the return to ‘traditional’ beauty norms.

When I went to the salon shortly after Lynch’s death, I knew I wanted do something to honor his passing. Caught between my love of red, Valentine’s Day just a couple of weeks away, and my grieving of David Lynch, I ended up with a manicure that inadvertently complimented the chevron of the Black Lodge floor.

I learned afterwards that David Lynch filmed a bizarre short film for Christian Louboutin about their first shade of nail polish inspired by their iconic red soles. The bottle constructs itself from the sharpened tip of a stiletto heel. The red of the polish floats around in an orb. We see a series of images of painted hands a la Lynch’s starlets, washed out by the camera’s flash like crime scene photos. We end up in these glitchy 3D-rendered landscapes which are so absurd that I can’t help but remember the special effects of Lynch’s Dune (1984). The soundtrack is some strange stuttering deconstructed jazz. Odd, impractical, yet entrancing—just like my choice in manicure.

Writer Francesca Segal noted in a 2016 British Vogue article that “For all the timeless optimism and glossy perfection of a fresh red nail, sometimes real life intrudes.” In David Lynch’s movies, red always symbolize that intrusion, that crossing over between dreams and fantasy. On the nails of his rebellious heroines and doomed victims, red marks the spilling of blood, the vibrancy of life, the brutality of death. It is a hue so saturated and artificial it can signify health, vigor, power, seduction, exploitation, pain, suffering, and paranoia—the paradoxical dualities and contradictions at the core of his cinematic storytelling. The red nails are worn by young women donning personas and trying to grow up, as well as older, exploited women ready to fight their way out of the world’s great evils. Lynch’s women can be dangerous, but they also symbolize the danger of being women. The American dream rendered into red lacquer masking the dirt under your fingernails.

Lynch also had an obsessive interest in the Wizard of Oz and I often feel like the red nail is a sort of ruby slipper symbol in many ways! Great piece 💅

read this with the same chipped red nail polish i’ve had on since i finished twin peaks for the first time and i didn’t even notice how prevalent it was 😭 stunning analysis